Filippo Rosati is the Founder and Artistic Director of Umanesimo Artificiale.

After an MSc in Marketing and Strategy from Bocconi University in Milan, and a double degree from the Copenhagen Business School, he worked in consulting and creative agencies in Europe and Asia. In 2017, he founded Umanesimo Artificiale where he is President, and has since focussed on art, science, and technology, mediating between disciplines and exploring interchange between art, design, robotics, biology and hacking, with an experimental approach to artistic and scientific research.

Umanesimo Artificiale was set up six years ago when I returned to Fano, in the Marche region, where I was born. After thirteen years’ experience in Europe and Asia, I wanted to launch a business activity in the field of artificial intelligence. Initially, the startup focused on creating business products, but my interest in artificial intelligence and new “exponential” technologies went beyond basic business software. I liked approaching the subject from a more visionary and speculative viewpoint. So, I decided to create a cultural association, Umanesimo Artificiale (which is still a no-profit, even though we are opening a studio in parallel). Through research, I wanted to identify something that sparked my curiosity: “What does it mean to be a human in the age of artificial intelligence?”. Technology has always accompanied and often accelerated human progress, but never like today has it reached such a level of self-learning able to approach the human thinking process so rapidly, taking command of expertise that was once considered unimaginable for a computer. Even more inconceivable, was the idea that a computer could perform these activities better than a human being. This forces us to redefine who we are as individuals, who we are within society. This voyage must begin with a process of introspection in which artistic channelling can play a very important role.

Umanesimo Artificiale – was set up because in this region (Fano, Romagna and Regione Marche) there were no activities involved in these areas, especially from an artistic point of view. It was born from a concrete necessity, and – as I often say – it made sense precisely because we are in Fano, a town with only 60,000 inhabitants. Even if we collaborate with other organizations in Italy and Europe, it is important to talk about Artificial Intelligence, cyborg art, and to propose events on art, science, and technology in places like Fano, to reflect on the impact of new technologies on society, so that they are not questions relegated only to large cities which are already saturated with these subjects.

I also like to recall that in the late nineties to 2000, Fano hosted the festival: – Il Violino e La Selce, under the artistic direction of Franco Battiato, with artists like Ryoji Ikeda, Pan Sonic, Coil, Bjork (in an exclusive performance) Steve Reich, Lou Reed and others.

Fano has always been culturally active and receptive, as far back as Roman times. In fact, Fano was a Roman colony and it offered hospitality to Vitruvius who mentioned the town in his – De Architectura.

We discovered that the public showed considerable curiosity, even though sometimes with a certain “reverential awe” towards the subject matter, sensitive for some people. However, I feel that art can help attract an increasingly wider public. As far as public institutions are concerned, I prefer not to comment, however, not being part of official institutions allows us to remain independent and to say and do what we prefer. Perhaps this might change in the future, I would like to think so. It might help that this year we have been assigned to curate one of the programs in the rich line-up of events for the – Pesaro 2024 Capitale Italiana della Cultura.

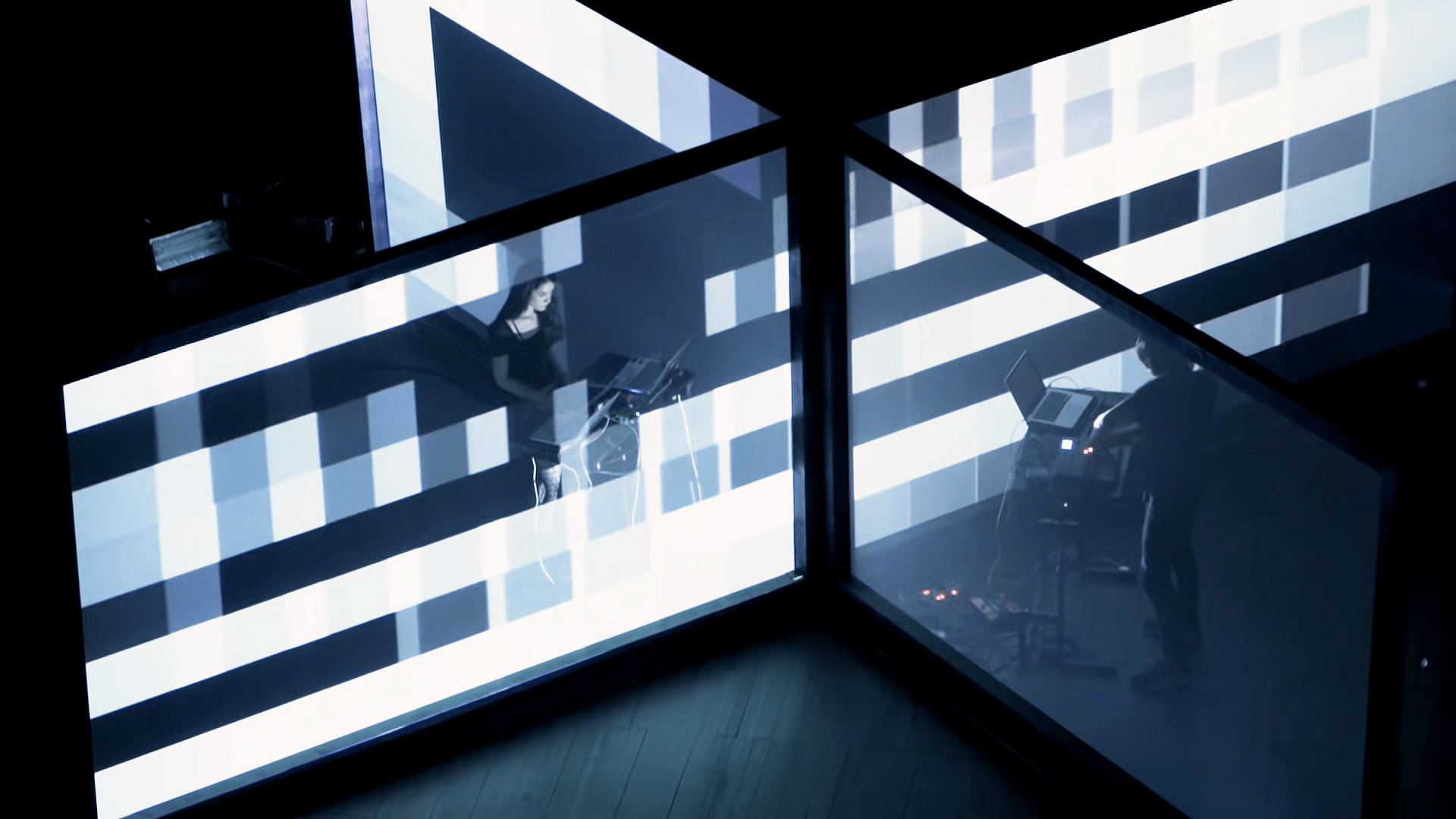

The first events were performances, with Nonotak and Robert Henke (Monolake) at the Teatro della Fortuna, and Caterina Barbieri at the ex Chiesa San Francesco, a spectacular open-air church in the center of Fano. From the very start, we held live-coding, processing, and touch-designer – workshops as well as – workshops for children on computational thinking and – scratch. We then evolved towards research projects, both on commission as well as internal personal research work. Today we have our – Transmedia Research Institute – that experiments new research formats and training. We are launching an – Operating system – studio for projects that we cannot carry out as a cultural association. However, the – Umanesimo Artificiale – cultural association continues to function for more interdisciplinary projects.

Everything grows and changes in an organic way, according to personal curiosity and the various connections and collaborations that emerge. In recent years the question “what does it mean to be a human in the age of artificial intelligence” has led us to investigate technologies that are becoming far closer to the human body, to the point of even penetrating it.

So we have implantables: transcranial implants like the – Neil Harbisson – cyborg, or neural implants such as Elon Musk’s – Neuralink; ingestibles like – Stomach Sculpture – by Stelarc or ingestible nanorobots; wearable technology: e-skin, second skin in biomaterials, and all the research by Luca Pagan on embedded technology. And finally, the technology around the body, understood as the concept of decomposition and multiplication of the body in networks.

I do not have a “conventional” artistic background, mine is more scientific and technological. Since I am just as interested in the final output as in the experimental process that I generate, from the beginning, I felt perfectly at home in the territory between art, science and technology. In my past as a consultant, I worked on projects that involved – MIT Media Lab – and certain professors, and I often visited them. – MIT Media Lab – – is a strong source of inspiration for – Umanesimo Artificiale.

There is a fantastic term used by the Boston – MIT Media Lab – – for this type of approach: “antidisciplinarity”, defined as a range of blank spaces between different disciplines, each with its own language, framework and methodologies. When I am asked questions on what we do, or about projects we are working on, I always answer that apart from the specific projects – many and very different from one another – what distinguishes – Umanesimo Artificiale – is the antidisciplinary approach we apply to each single project. This is what we are recognised for; it is what our public and our partners expect, and what we look for in those who collaborate with us.

We work on projects where the artistic and scientific aspects begin together on day zero, at the same level, and then we go ahead in parallel mode, each one influencing the other. It is a more complex system than embellishing a scientific experiment or calling in a scientist later on to make an artistic project more scientifically credible, but it produces good results.