TikTok Refugees, little red books and banned apps

by Camilla Fatticcioni

The recent announcement of a TikTok ban in the United States has driven millions of American users to search for alternatives, including the Chinese app RedNote. This digital migration has sparked an unprecedented cultural exchange between the West and the East.

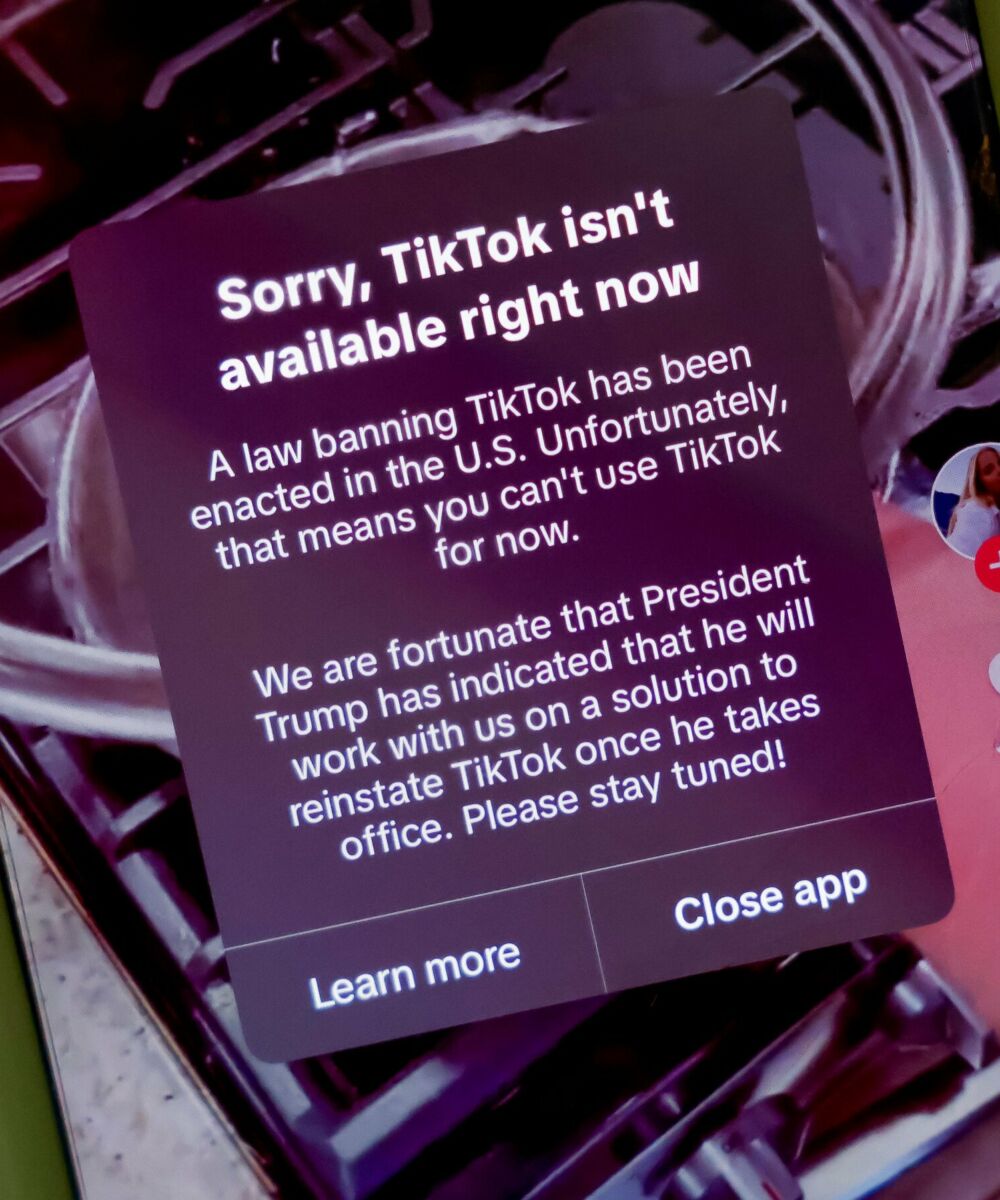

In recent weeks, we have heard talk of TikTok refugees, “little red books,” and apps being banned and then reinstated. It all began in January 2025 when the U.S. Supreme Court judges unanimously upheld the so-called “TikTok ban.”

The backstory of this matter has roots in legislation adopted by the outgoing Biden administration, which last spring approved a law aimed at banning the use of the popular social media app TikTok in the United States. According to American authorities, the Chinese company ByteDance, which owns the platform, is accused of collecting and manipulating users’ personal information—there are around 170 million TikTok users in the U.S.—to pursue political objectives. Specifically, the U.S. government argues that TikTok could exploit its powerful algorithm to influence public opinion, steering content in targeted ways to manipulate perceptions and shape political debates. On January 19, just hours after the app was banned, TikTok was reinstated following an intervention by incoming President Donald Trump. Shortly before, the newly elected president had pledged to issue an executive order after his inauguration on January 20 to postpone the ban for 90 days, giving ByteDance time to find a buyer and thus avoid the prohibition.

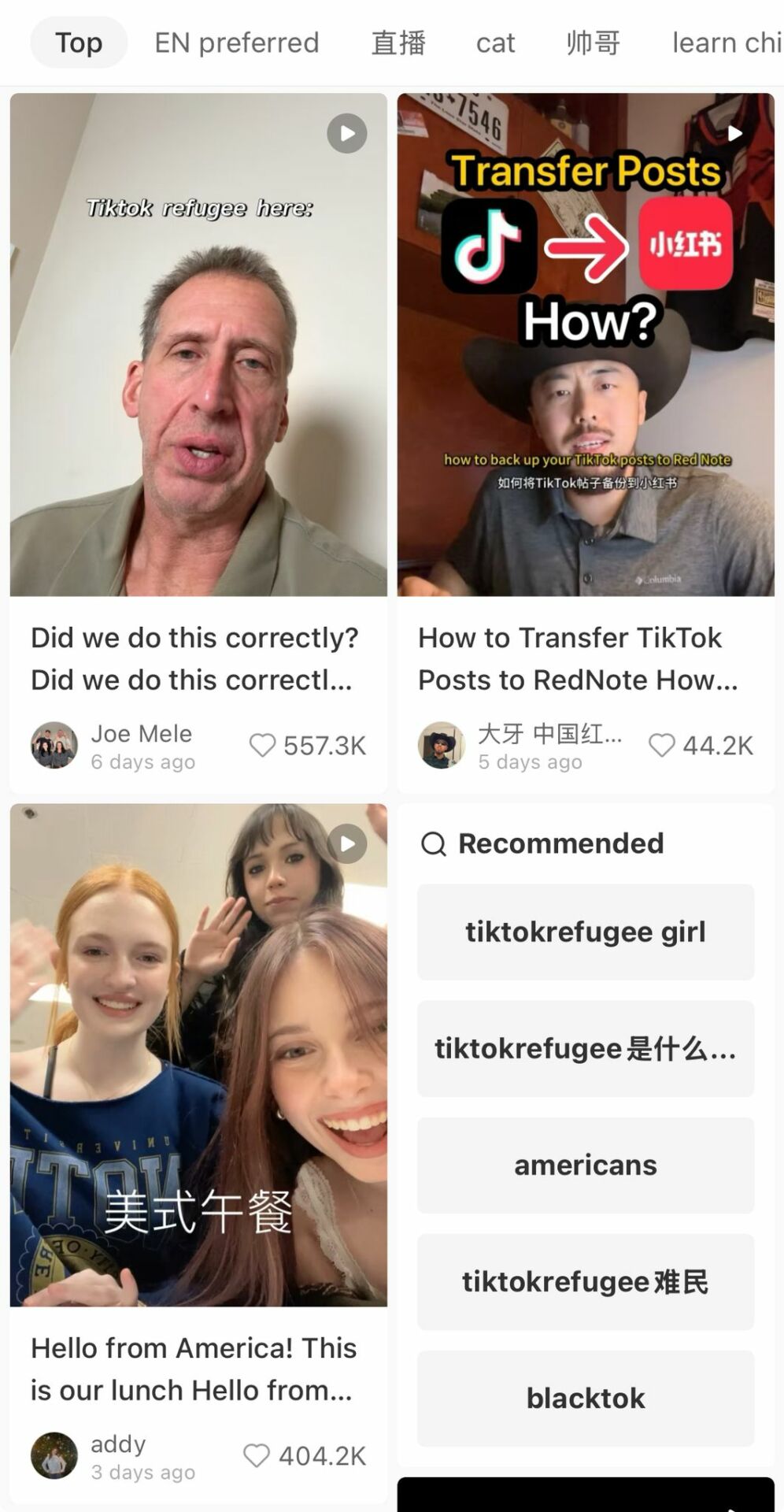

The announcement of the app’s removal from American platforms nonetheless prompted many U.S. users to seek refuge online elsewhere, and many turned to the Chinese social media platform RedNote, also known as Xiao Hong Shu (小红书), which literally means “little red book.”

The platform, particularly popular in China but virtually unknown in the West until recently, has seen over 700,000 new American users join in recent weeks, making RedNote the most downloaded free app in the United States.

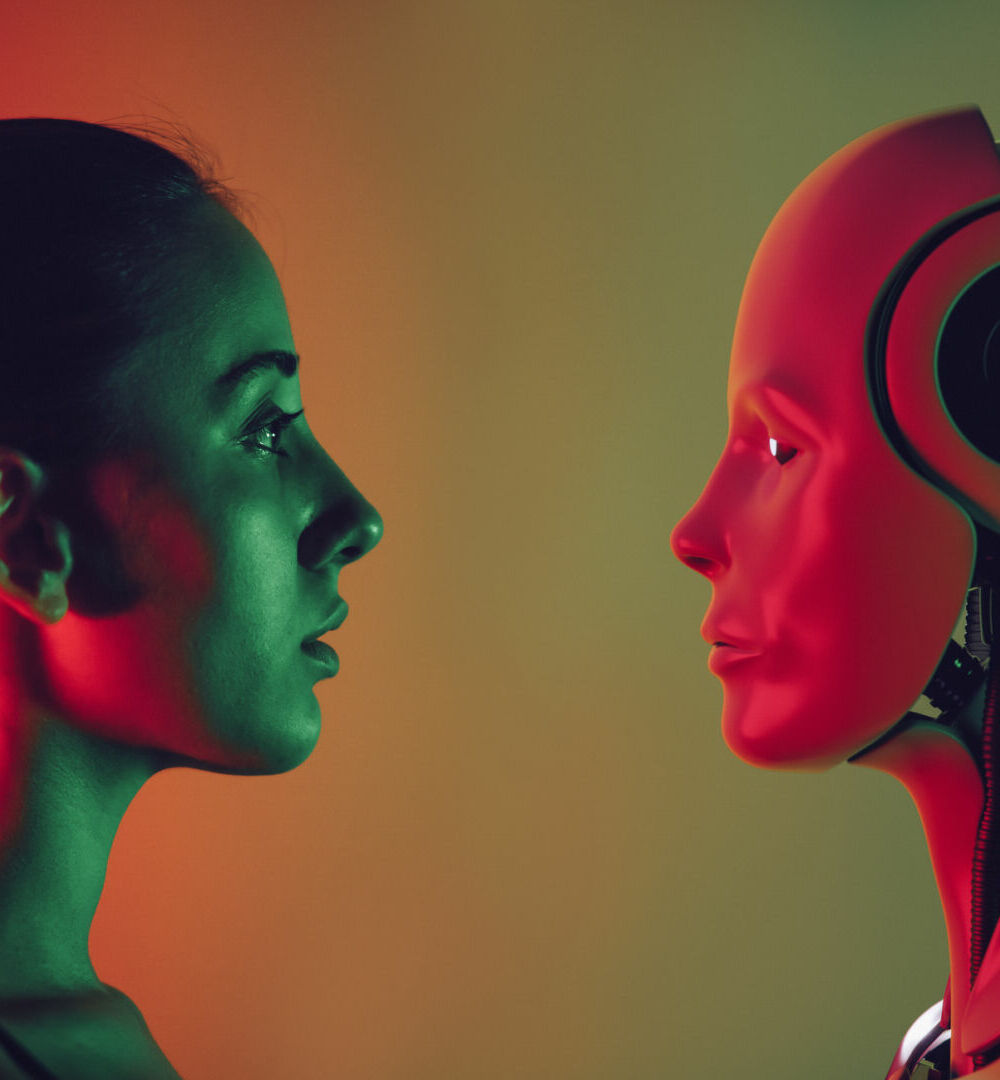

This encounter between East and West on the app has sparked an unexpected, awkward, yet genuine dialogue between overseas users.

But why RedNote? Some joined as a form of protest, deliberately choosing another Chinese app after losing access to TikTok. Others wanted to avoid using Instagram or other Meta-owned platforms. As one user put it in a video, “I’d rather keep watching a language I can’t understand than use a social media platform owned by Mark Zuckerberg.”

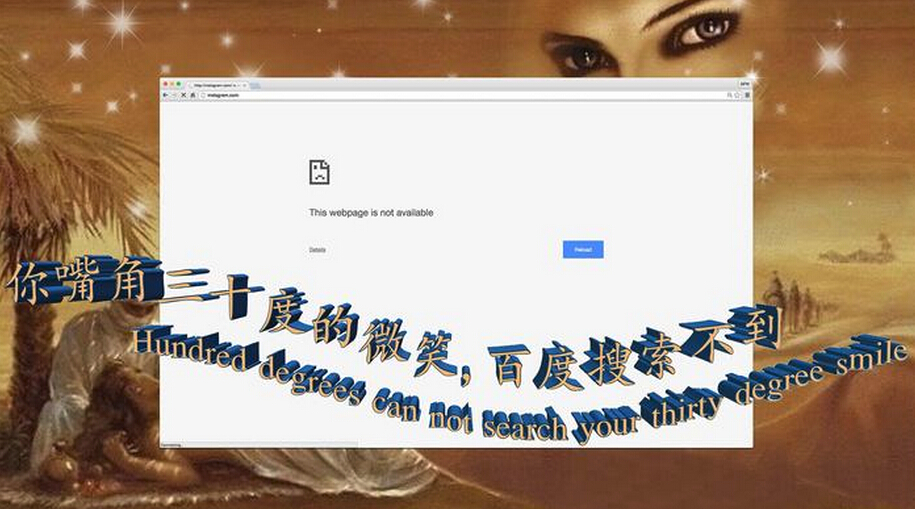

Never before has the West interacted so directly with the Chinese internet—partly because China’s digital sphere is largely separated from the rest of the world, and partly due to language and cultural barriers. Even TikTok itself offered a “Westernized” version distinct from Douyin, its counterpart available in China. The arrival of TikTok refugees—what the new American users on RedNote have called themselves—has suddenly opened a cultural dialogue between ordinary people in the U.S. and China, where users are unaccustomed to seeing so much content posted by foreigners.

But let’s clarify: what kind of social platform is RedNote? Like most Chinese apps, RedNote is multifunctional—it combines elements of Instagram, Pinterest, TripAdvisor, and Amazon, and is also heavily used as a search engine. It’s especially popular among Chinese expatriates for sharing lifestyle advice (as journalist Lucrezia Goldin explains in this interview). Originally designed to guide Chinese consumers toward overseas shopping, it has since become the most popular social media app in China, thanks in part to a powerful algorithm that allows new users to reach a broad audience and gain followers with minimal effort.

This encounter between East and West on the app has sparked an unexpected, awkward, yet genuine dialogue between overseas users.

The TikTok refugees have had to adapt to the codes of Chinese web culture, filled with ironic memes, while Chinese users have begun offering advice on how to best use RedNote, jokingly calling themselves spies stealing data and asking the newcomers to pay a “pet tax”—posting photos of animals to continue using the app.

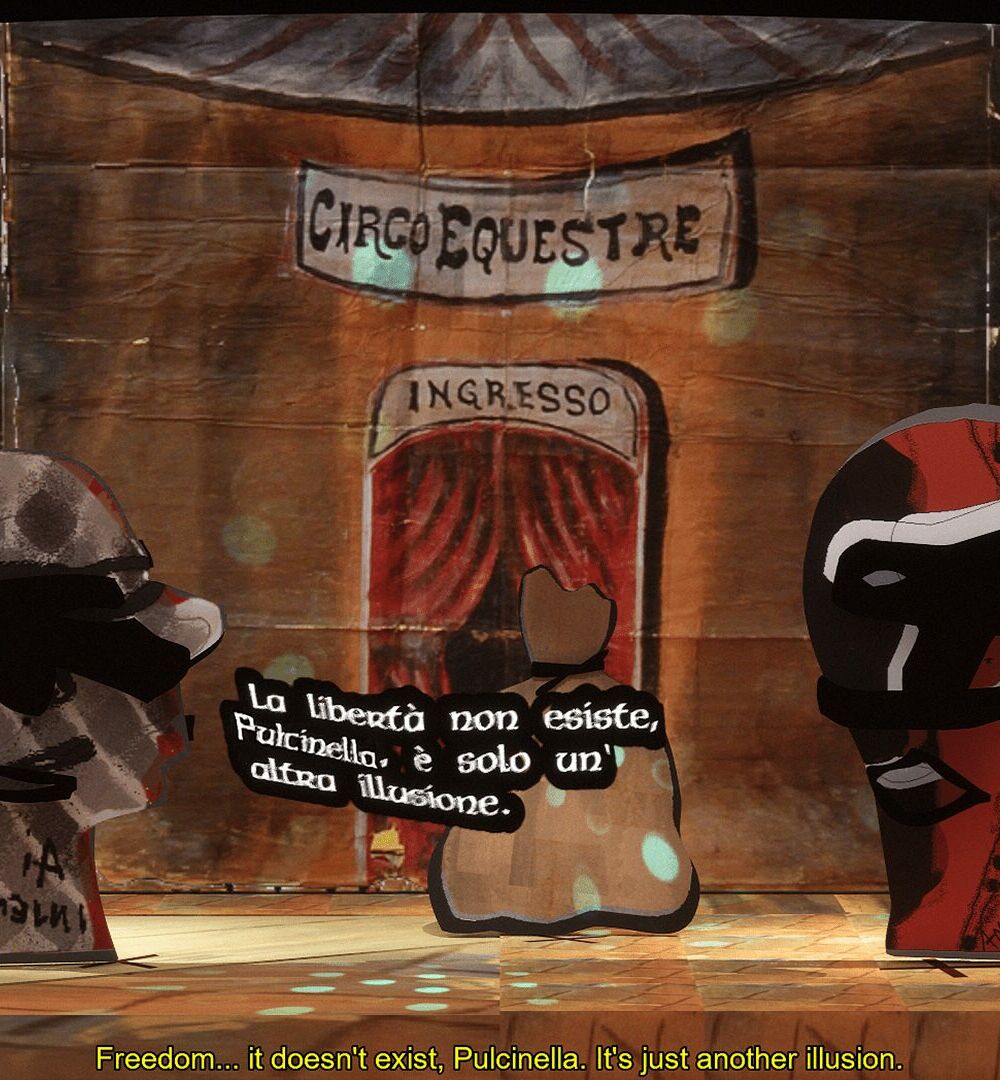

Many American users have also noticed the heavy content censorship typical of Chinese social media, prompting questions about the app’s often arbitrary guidelines. Veteran RedNote users, somewhat bewildered, have welcomed their American counterparts, exchanging opinions on topics like food and youth unemployment. Occasionally, however, Americans have broached more sensitive subjects: “Can I ask how the laws differ between China and Hong Kong?” one American user queried. “We’d rather not discuss that here,” a Chinese user replied.

One thing is certain: even RedNote did not anticipate this sudden surge of international popularity. But will the hype last? The company is eager to capitalize on this wave of attention; English-language advertisements promoting the app have recently appeared on Instagram.

For now, RedNote maintains a single version of its app rather than dividing it into domestic and international versions as TikTok did—a rarity among Chinese apps, which are typically subject to national moderation rules.

This could signal the beginning of a new kind of globalization—one less driven by capital, technology, and goods, and more connected to the lives of ordinary people.

Camilla Fatticcioni

China scholar and photographer. After graduating in Chinese language from Ca’ Foscari University in Venice, Camilla lived in China from 2016 to 2020. In 2017, she began a master’s degree in Art History at the China Academy of Art in Hangzhou, taking an interest in archaeology and graduating in 2021 with a thesis on the Buddhist iconography of the Mogao caves in Dunhuang. Combining her passion for art and photography with the study of contemporary Chinese society, Camilla collaborates with several magazines and edits the Chinoiserie column for China Files.