The girlies love the vibes and that’s just what it’s about

by Viola Giacalone

A brief history of the zeitgeist, or how ‘vibes’ went from being the emotional language of a close-knit community to fuelling an entire economy.

In an article published in Spike Art Magazine in August, entitled ‘No Thoughts just Vibes’, author Anna Kornbluh states that ‘vibes’, vibrations, are the Zeitgeist, the cultural spirit of our time. In 2022, an article appeared in ‘The Cut’ magazine, later republished by New York Magazine, entitled ‘A Vibe Shift Is Coming Will Any Of Us Survive It?’, which hypothesised a telluric movement, a ‘vibe shift’ that would disrupt the way we dress, date and listen to music. Without bothering with international editorial realities and cultural eras, a friend I spoke to earlier, referring to the guy she is dating, said: ‘we are at that stage of the relationship where you need to do a vibe check’.

frivolity and irrationality always attributed to women is reappropriated with self-irony, but that's not all: in a world of genocides and wars , an approach to life that is based on listening deeply to one's own emotions and those of others is no longer so frivolous.

Vibes, understood as intangible sensation and energy, have recently become solid and concrete to the point of fuelling an entire economy, what one of the world’s largest communications agencies We Are Social* has renamed the ‘vibe economy’: ‘a new generation of social content – one that connects people through complex moods and feelings, not just simple interactions.’

The term ‘vibes’ in its Anglophone form became popular from the 1960s onwards, when the New Age, the interest in psychedelia and Eastern spiritualities spread in the West. We also find it in funk and soul music and then in the hip hop and r&b of the 1990s and 2000s, with the same meaning as ‘groove’ or ‘flow’, another type of spirituality. The internet world is rightly credited for bringing it back into vogue, but it can be argued that it is mainly the girls and the LGBTQIA+ community who have nurtured this way of reading the world, creating a system of mutual influence and synergies online, from the heyday of Tumbrl to the present day. The world of feelings, of intuition, of the irrational has been associated with the feminine for centuries, an association that has cost the lives of thousands of women in the times of witch hunts, and a stereotype that has weighed on millions of other women, excluded from different spheres because of their ‘sensitive nature’.

Today, ‘feminine sensibility’ is proudly claimed, as evidenced by the renewed interest in online witchcraft, or the meme ‘I’m just a girl’, for which the frivolity and irrationality always attributed to women is reappropriated with self-irony, but that’s not all: in a world of genocides and wars dictated by supposedly rational thinking, an approach to life that is based on listening deeply to one’s own emotions and those of others is no longer so frivolous.

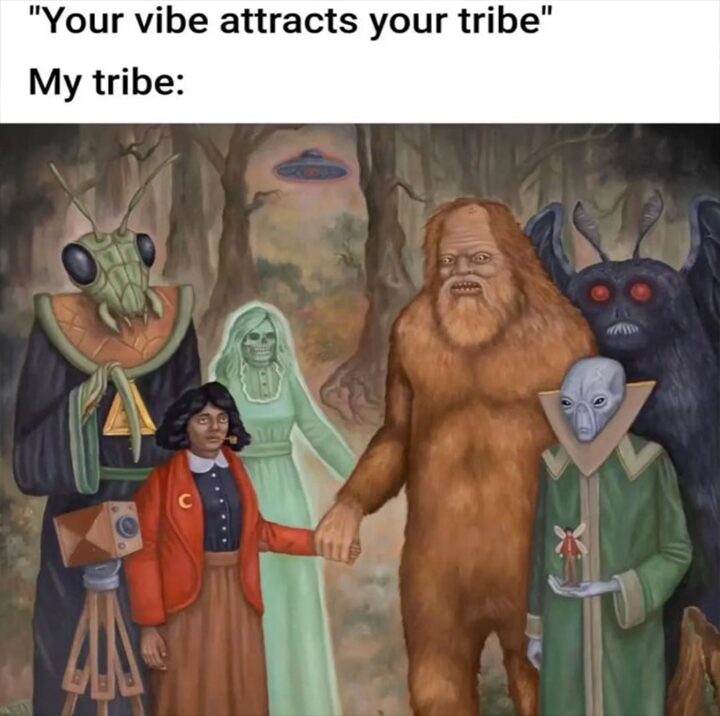

‘I know the influence, I know the impact, and I know the vibes! The girlies love the vibes and that’s just what it’s about’ is a quote by the it-girl and actress Julia Fox that has become a leitmotif in various spaces on the web and sums up well the semantic meaning that vibes have recently acquired. Since the ‘10s on Tumbrl, girls have created digital communities based on sharing images, through mood boards, literally, “mood boards”, creating very precise “aestethics”, still in vogue on Pinterest and Tik Tok.

The ‘vibes’ that a certain profile conveyed were an intuitive language that allowed people to identify and connect with their peers. The term ‘vibes’ started to spread as hashtags and then became a cultural paradigm even outside the web, imposing itself in the art, film, fashion and music markets, both in terms of production and consumption. As is often the case when the mainstream attempts to absorb an avant-garde, we observe a trivialisation and commodification of something potentially ‘subversive’: in this case, a coming together of unknown queer people who connect with each other on the Internet on a non-profit basis because they have the same intuitions, which is transformed into cultural products that are perhaps simpler, perhaps more superficial, sometimes inaccurate. I am thinking of the ‘vibes-isation’ of cinema par excellence, the Netflix productions, in which the care for atmosphere commands over script and plot. The success of one of these series is a promise of a string of future series that will have the same vibe.

I think of clothing brands that ascribe ‘90’s vibes’ to garments that actually emulate the 2000s. The hope is that the vibe remains high without the purely aesthetic aspect of things taking precedence over their actual value, that the vibe remains the soul of things, and not something that skin care brands can sell.

*The vibes were definitely ‘off’ in the Italian branch of the ‘We Are Social’ agency, which has made itself known for very serious stories of harassment and sexist chats by some of its members against female colleagues. it has been called the #Metoo of the Italian advertising world. Another example of how big companies and corporations try to hide toxic work dynamics behind a fresh and contemporary image.

Viola Giacalone

Viola Giacalone, or Viola Valéry, born in Florence in 1996, is a Florentine journalist, writer and memer. She graduated in comparative literature at the Sorbonne Nouvelle in Paris, with a master’s thesis on new creative writing on the web. She continued her studies in cultural journalism at the City College of New York and at the Accademia Treccani in Rome. She currently collaborates with various publishing, cultural and radio organisations (Controradio Florence, RadioRaheem Milan).