Syntax War

Language as a Battlefield: From Political Framing to Algorithmic Networks

by Martina Maccinati

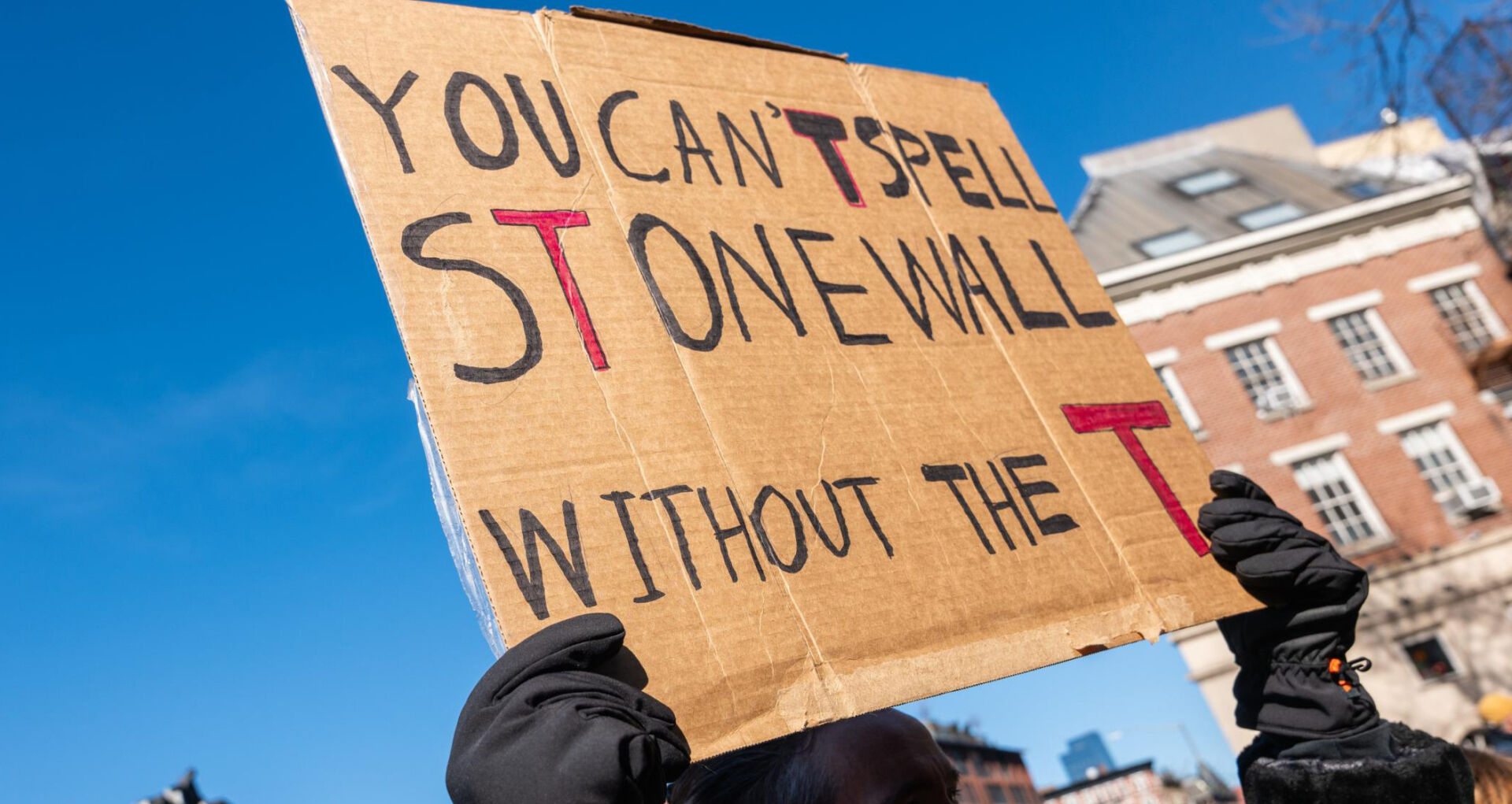

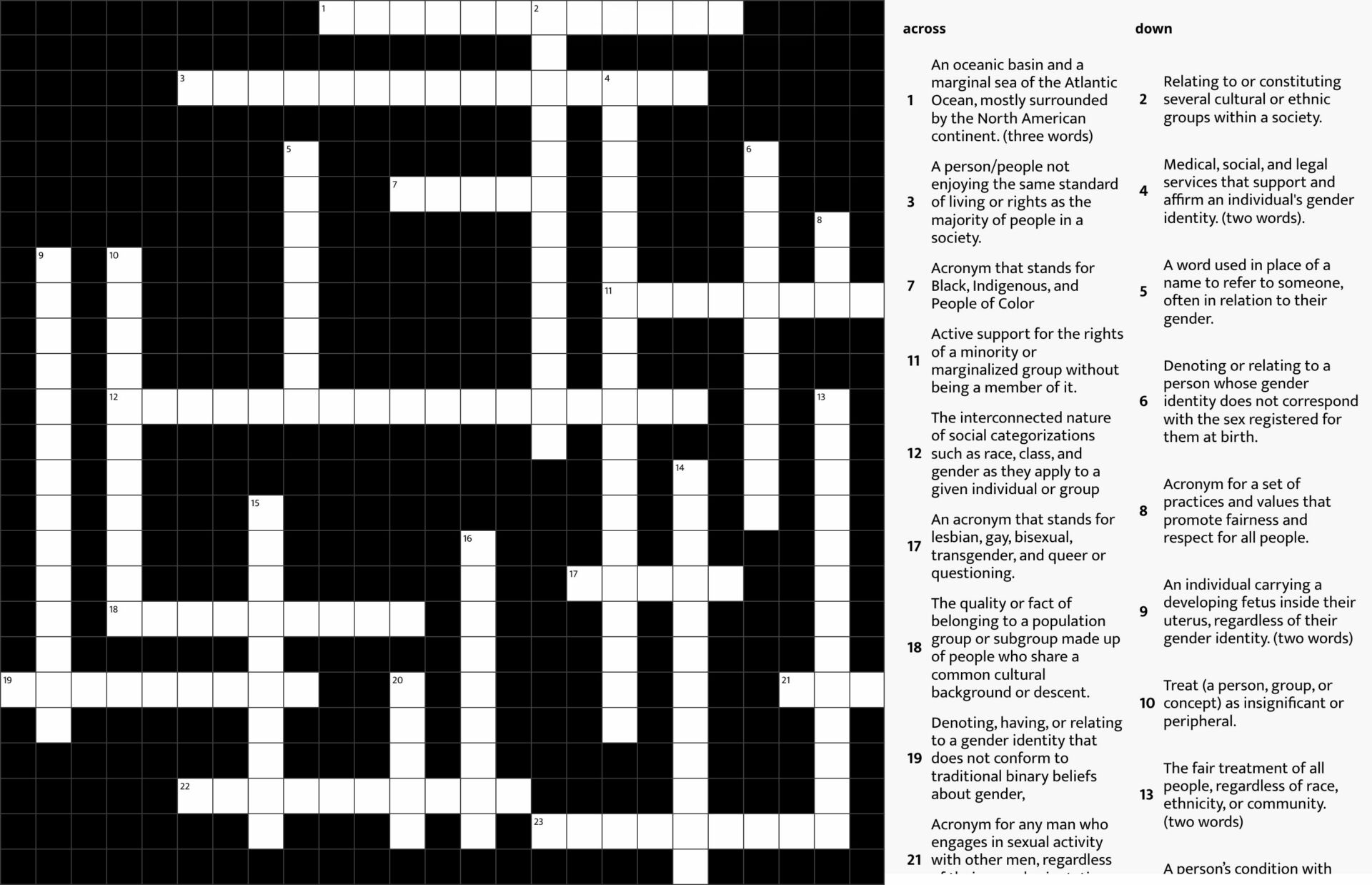

Recent news has reported Donald Trump’s decision to introduce a list of “banned” words—terms that should no longer appear, or should be significantly reduced, in official documents in order to align with his political vision.

George Lakoff, a linguist and professor of cognitive linguistics at the University of Berkeley, has centred his work on the concept of framing. A frame represents the cognitive framework within which a concept is presented, influencing how it is understood. This mechanism, extensively exploited in political and media communication, highlights the power of language in shaping thought. According to Lakoff, the way political concepts are framed directly affects voters’ perception and behaviour. Frames are mental structures that help interpret reality: when a politician uses a certain language, they are not merely conveying information but are activating a specific frame in the minds of listeners, shaping their interpretation of the issue. Lakoff’s lesson is simple: whoever controls the frame wins the debate.

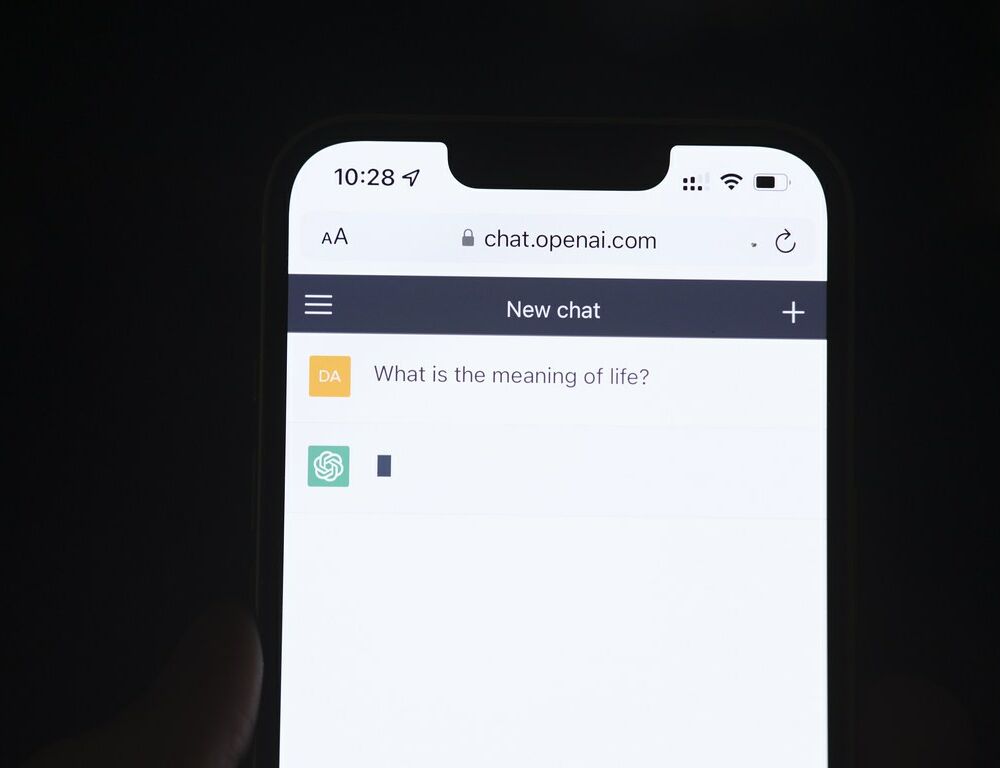

Having established this necessary framework of thought, let us return to the initial point. The idea that certain words can be banned inevitably leads us to reflect on how language has always been a political weapon; however, today this weapon operates in a context where language itself is constantly redefined by digital technologies. Whereas power was once exercised primarily through censorship or the redefinition of meanings, today it also manifests in the very architecture of communication: algorithms decide what we see, which words gain visibility, and which are relegated to the margins. While language remains a weapon—a technology capable of shaping the perception of reality—it also raises significant questions about the very nature of communication in an age of increasing automation.

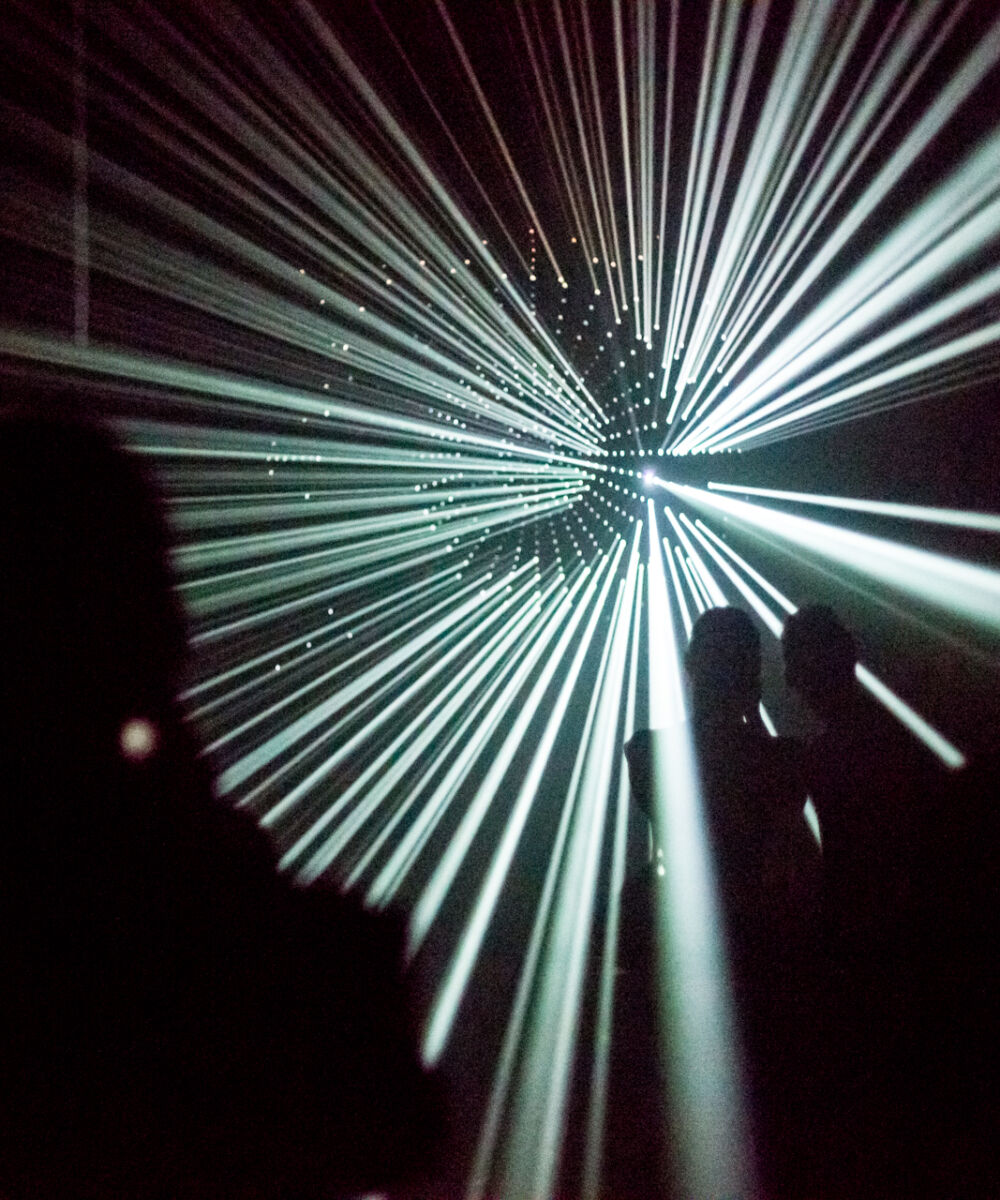

While human language is always a situated act, rooted in intentionality and history, machine language operates in a space of pure simulation, where verisimilitude replaces truth and appearance becomes indistinguishable from reality, leaving us with new spaces for resistance, imagination, and action.

Western philosophy has often considered language as a foundational structure of human subjectivity, a system of representation that allows us to exist as speaking beings. From Saussure to Lacan, language has been conceived as a set of signs that constitutes and defines us. For Lacan, entry into the symbolic order is what renders us subjects: language is not merely a tool of communication but the medium through which desire is structured and transmitted, in an infinite play of slippages and differences. This conception implies a view of language as exclusively human, rooted in a logic of representation and depth. The subject is the one who speaks, but at the same time, the one who is spoken by language.

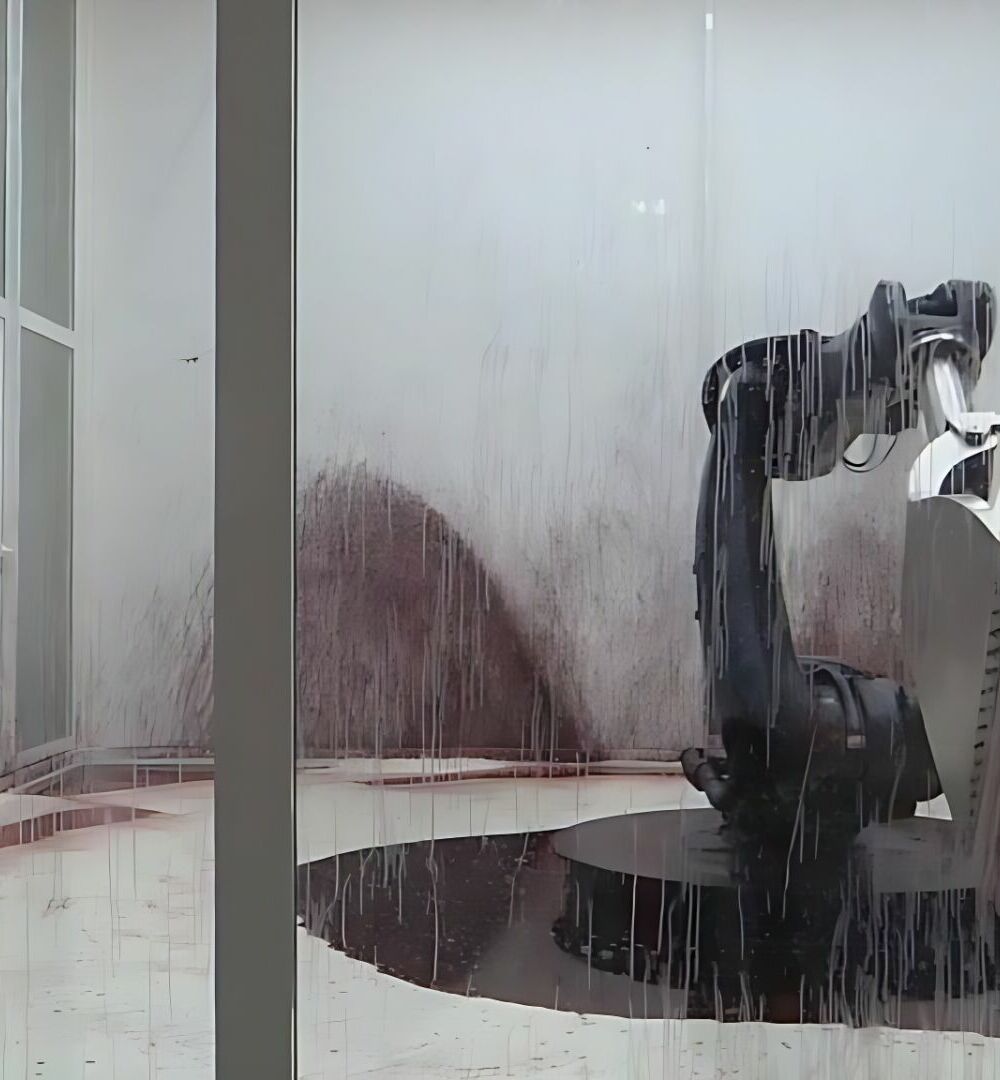

But what happens when language is no longer solely human? Katherine Hayles, one of the most influential voices in posthuman theory and contemporary media studies, has focused her research on the relationship between technology, information, and subjectivity, exploring how digital culture and cybernetic systems have transformed our understanding of the human. In her studies, Hayles proposes a radical shift from this linguistic tradition: the advent of digital technologies and cybernetic systems introduces a new dimension of communication, where language is no longer merely a symbolic system but a flow of information. Hayles’ work represents one of the most radical deconstructions of the symbolic paradigm in contemporary philosophy. Her reflection demonstrates how human language is no longer the sole system of signification but one of many circuits through which information circulates and organises itself. In effect, Hayles has paved the way for a new ontology of subjectivity. While symbolic language is based on the representation of meanings, cybernetic information is founded on the transmission of patterns and signals. In this paradigm, the subject is no longer the centre of meaning production but a node in a distributed processing network. Subjectivity becomes an emergent property of information circulation.

The hybridisation between human and non-human reshapes our position in the world, our possibilities for action, and our ability to hack what we consider defined and beyond our competence.

If in human language truth has always been a nuanced concept, mediated by interpretations and cultural constructions, in machine language, meaning is not sought but rather statistical correlation and data transmission optimisation. In this perspective, we face a paradox where we can trace a fracture and explore new possibilities: while political censorship attempts to control language by imposing bans and new frames, technology enacts another form of fragmentation—subtler but perhaps more radical—by deciding what is relevant based on computational efficiency criteria.

This shift in perspective and scale implies that we are no longer the sole producers of meaning: subjectivity becomes an emergent effect of our interaction with machines and digital networks. The hybridisation between human and non-human reshapes our position in the world, our possibilities for action, and our ability to hack what we consider defined and beyond our competence.

Trump’s decision to ban certain words reminds us of the power wielded through language, but it also opens our eyes to a different history: linguistic control, and consequently the representation of reality, is now exercised not only through explicit prohibitions but also through the very architecture of communication. In an era where language is no longer solely human but part of an ever-evolving digital ecosystem, the challenge is not merely to defend language from political interference but to rethink our relationship with it. The real revolution might not be just about teaching machines to understand language, but imagining new ways to inhabit this intermediate zone between the human and the artificial, between the symbolic and the computational, between control and rewriting, in order to achieve a true shift in meaning—one that surpasses a politics clinging tooth and nail to every word and construction.

Martina Maccianti

Born in 1992, he writes to decipher contemporaneity and the future. Between language, desire and utopias, he explores new visions of the world, searching for alternative and possible spaces of existence. In 2022, he founded a thought and dissemination project called Fucina.