Luigi Mangione has ended up in a video game

by Matteo Lupetti

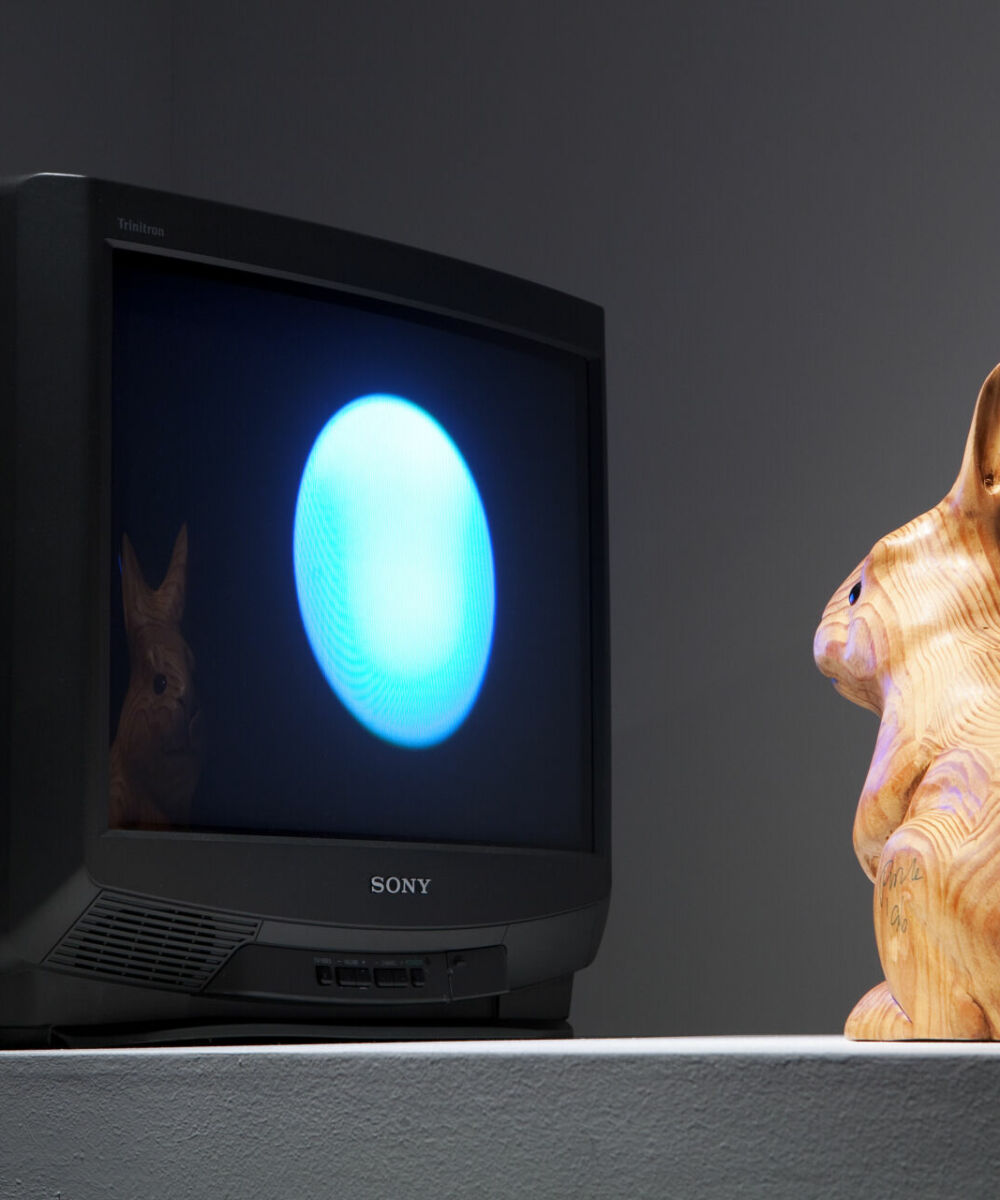

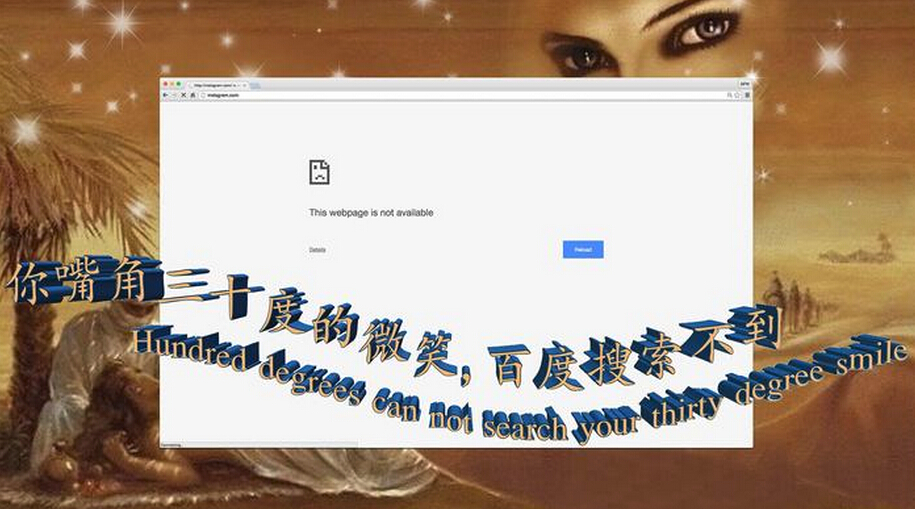

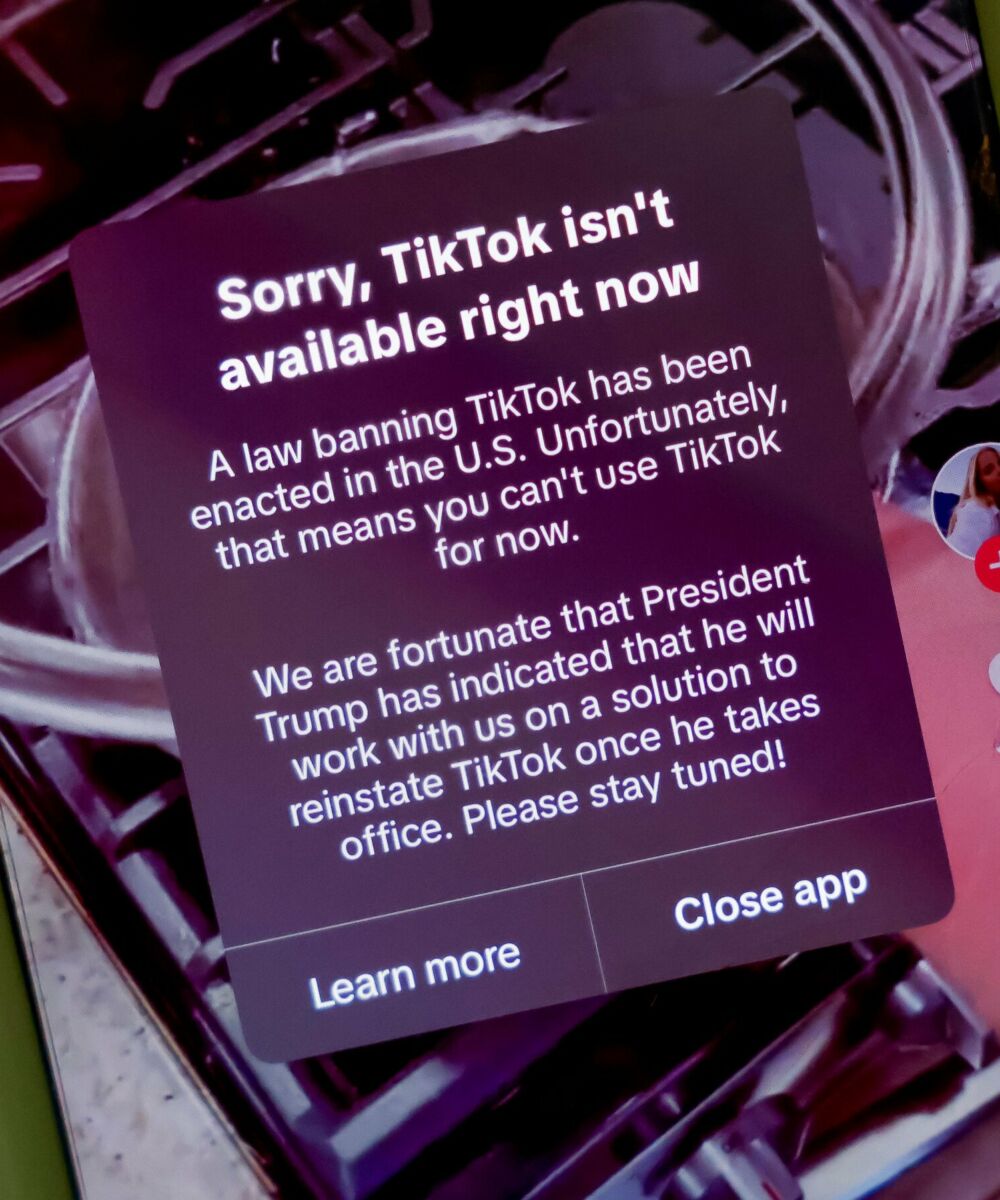

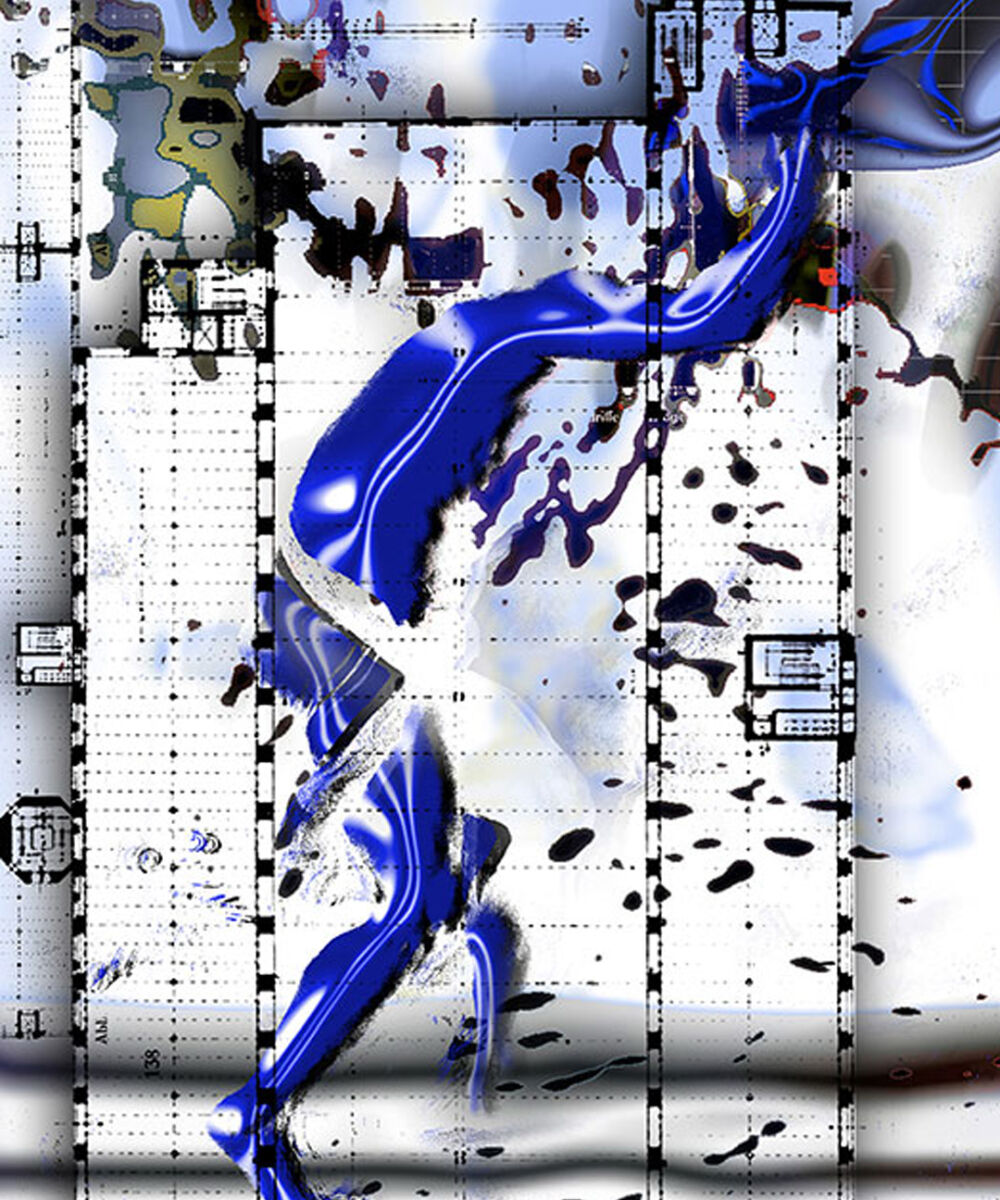

In the video game détournement yuri lowell prints a gun by Flan Falacci (2025), we explore a three-dimensional environment where scenes from the Japanese fantasy video game Tales of Vesperia (Namco Bandai Games, 2008), retrieved from YouTube videos, alternate with images, excerpts from articles, memes, and social media posts concerning Luigi Mangione, who was arrested as the main suspect in the murder of Brian Thompson, CEO of the multinational health insurance company UnitedHealthcare, who was killed in New York City on 4 December 2024, apparently with a 3D-printed gun.

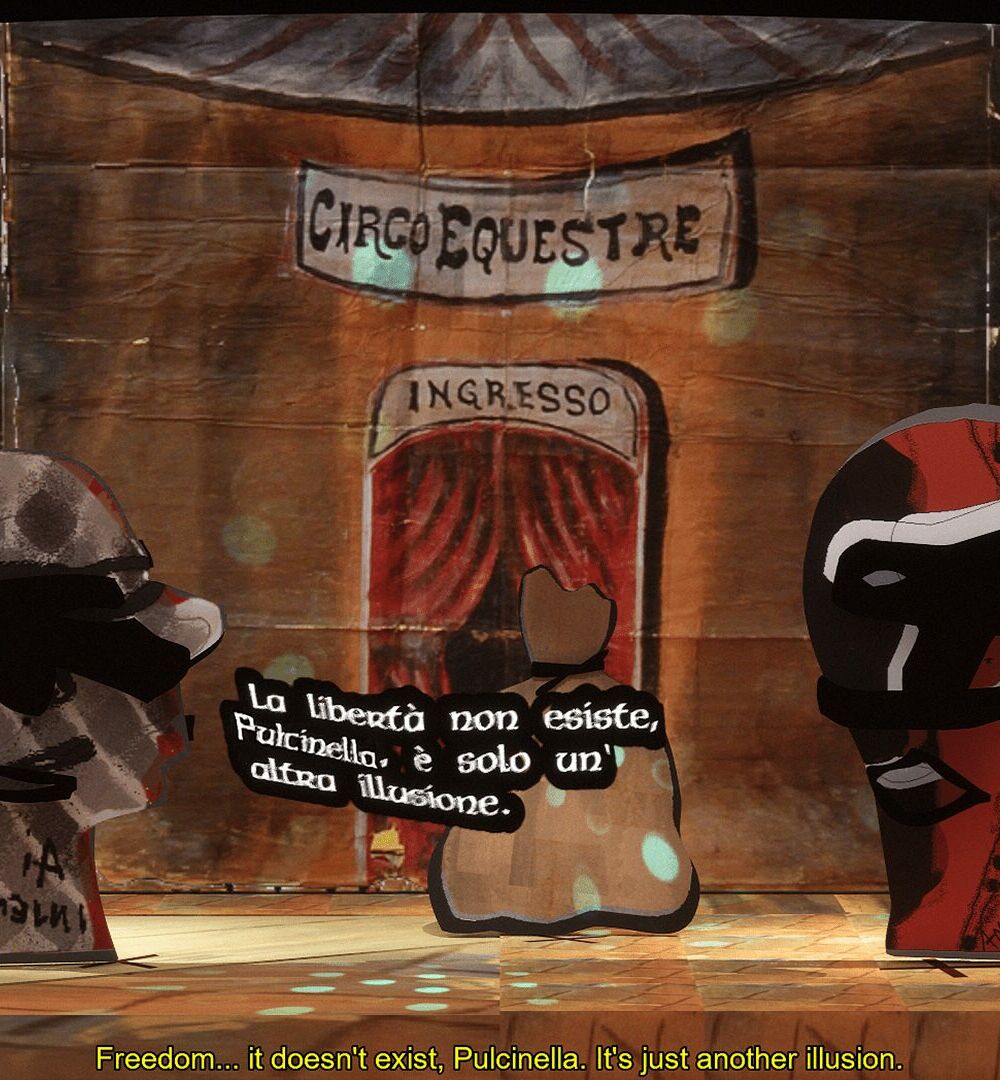

Mangione, who became an online folk hero, allegedly wanted to punish Thompson for the policies of UnitedHealthcare and other American health insurance companies, which aim to delay and deny payments to those in need as much as possible. In Falacci’s work, Mangione and Thompson’s story resonates with a subplot from Tales of Vesperia, in which the protagonist Yuri Lowell, realising that the legal system would never punish (and never intended to punish) one of the game’s antagonists, Captain Alexander von Cumore, decides to take matters into his own hands and kills him.

In yuri lowell prints a gun, the physical world, its media representation, and the virtual world collide in a collage of digital ready-mades, videos, images, and pre-existing 3D models that continue to carry their original contexts and meanings. Tales of Vesperia is recontextualised, while public support for Mangione is placed within a broader discussion on violence as a political tool.

yuri lowell prints a gun is a “plundercore” game, a video game constructed through the often subversive reuse of assets (audiovisual elements) and parts of other—mostly commercial—video games. “There seemed to be a lot of people making games in this style in a way that felt like a new trend or movement or something, a lot of them coming out of the NYU games programme, I think?” developer JohnLee Cooper writes to us. Besides creating plundercore games himself, he also curates a collection dedicated to the trend on the online platform itch.io. “Art unbounded by copyright law gets to reinterpret old works in a new light, go places their corporate sources wouldn’t dare to. It also draws attention to the materials of a game, revealing the mixed-media nature of the medium, really makes you think about models and texture.”

L’arte liberata dalle leggi sul diritto d’autore getta nuova luce su vecchie opere, arriva in luoghi dove non oserebbero addentrarsi le compagnie originali. Sposta anche l’attenzione sui materiali che costituiscono un gioco, rivelando la sua natura di opera mixed media, e ti permette di concentrarti davvero su modelli 3D e superfici

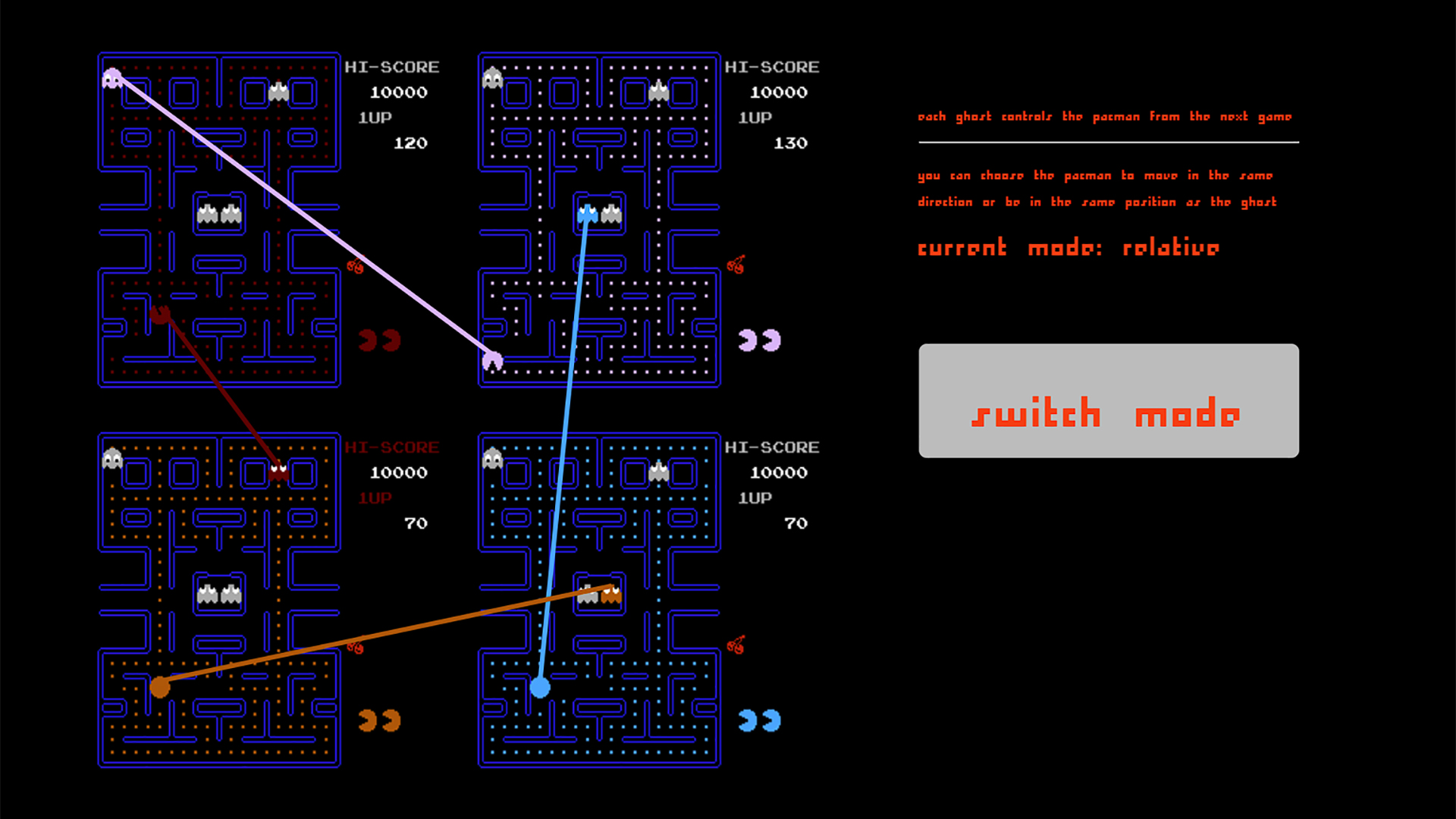

Closely linked to plundercore are plunderludics, video games created not only with assets from other games but also with their actual code. The original games are modified or emulated (essentially, made to run) within the new work, blended with other video games or their elements. “As for plunderludics, I see it as an extension of the appropriation of characters [in plundercore] to the complete appropriation of the video games (and games) themselves,” writes Gustavo “mut/moochi” Ceci Guimarães, who coined both the terms plundercore and plunderludics, derived from plunderphonics—a musical practice of composing using samples of existing and recognisable recordings (where to plunder means to loot or pillage).

Mut is part of the Plunderludics Working Group, alongside Gurn Group and Johnny Hopkins. This collective is dedicated to plunderludics and develops specific software for their creation, such as UnityHawks, a tool that integrates the BizHawk emulator—a programme capable of running old console games on modern computers—into Unity, a popular game development toolkit, to facilitate the creation of digital works that interact with existing games. The Plunderludics Working Group also organises events at a physical venue, Boshi’s Place in Brooklyn, and Falacci developed yuri lowell prints a gun for one such event (Year of Luigi, 18 January 2025, with an opening on the 17th).

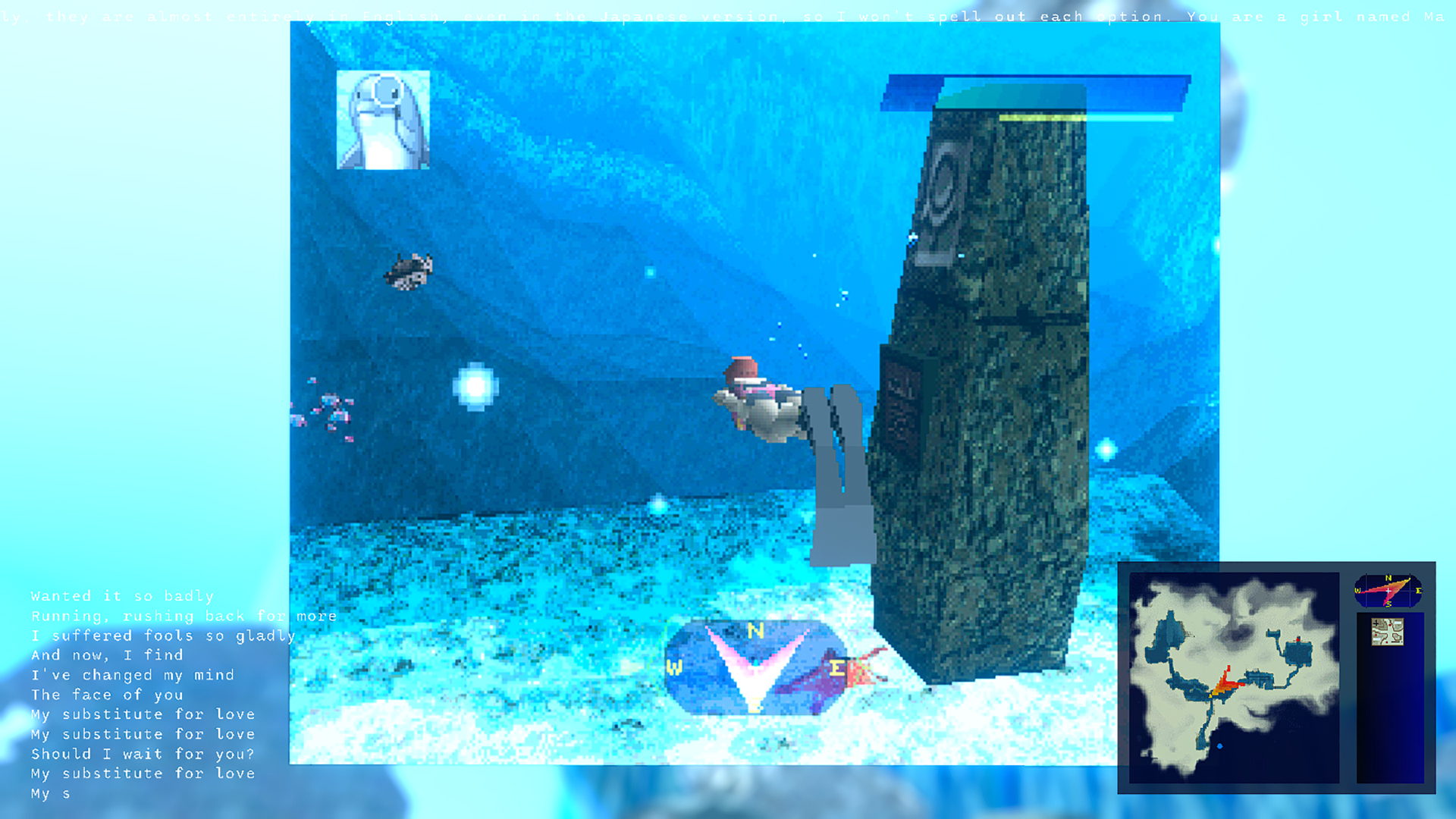

The video game détournements of plundercore and plunderludics can serve various purposes, some more political than others: estrangement, satire, reinterpretation of elements already present (perhaps subtly) in the original works, critique, and, especially in the case of plunderludics, the study of game mechanics and interactions. For example, the plunderludics game Water Level/b.l.u.e. EXPLORATION by Hatim “hatimb00” Benhsain is a playable poetic essay centred on the video game b.l.u.e.: Legend of Water by CAProduction and Hudson Soft Company (1998). The game is emulated within the new work using tools developed by the Plunderludics Working Group and mixed with assets from other games, texts, and songs, including Drowned World/Substitute for Love by Madonna. The result is a video game collage that not only introduces Western audiences to b.l.u.e.: Legend of Water, originally released only in Japan, but also expands into a psychedelic journey through the representation of aquatic worlds.

Though they have only recently begun to be defined and studied as broader trends, these practices of reusing existing commercial video games to create new ones have a long history. As early as 2013, two video games were released that could now be considered proto-plundercore and were highly influential on the movement: with all my heart by donnytuplis and Bubsy 3D: Bubsy Visits the James Turrell Retrospective by Arcane Kids. The Plunderludics Working Group itself includes mods—unofficial modifications of commercial video games that sometimes result in entirely new works—within the category of plunderludics. More generally, making games based on other games falls within the concept of “metagaming,” explored by Patrick LeMieux and Stephanie Boluk in Metagaming: Playing, Competing, Spectating, Cheating, Trading, Making, and Breaking Videogames (University of Minnesota Press, 2017), which is central to the development of the plunderludics movement.

Metagames are games built upon other games. However, according to LeMieux and Boluk, in reality, “metagames are the only kind of games that we play.” Every game is situated within a context that influences and alters it, creating a metagame that we ultimately play, and every game becomes part of an assemblage of human and non-human agents, integrating into complex systems that can never be fully comprehended. Metagaming thus encompasses everything that happens before, during, around, and after the game, shaping the experience: it treats games not as ideal objects but as practices occurring in specific times and places.

Since the birth of the industry in the 1970s with Pong (Atari, 1972), video games have been positioned as consumer goods—something to be purchased and consumed in specific ways by following fixed rules before moving on to the next product. At the heart of this privatisation of play is a deception: the gaming industry has conflated what are called “mechanics” with the “rules” of its games. A video game’s mechanics are all the processes, defined by software and hardware, that players cannot alter without modifying the software and hardware (for instance, through hacking). These are processes not chosen voluntarily but fixed in the materiality of the video game. Game rules, on the other hand, are social conventions that we accept or reject freely.

The materiality of a video game defines its affordances, a term introduced by James J. Gibson in The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception (Houghton Mifflin, 1979; Italian translation: L’approccio ecologico alla percezione visiva, Mimesis, 2014)—in other words, the possibilities that a game offers. The form of any tool encourages or discourages certain uses. But what we do with it, what rules we choose to follow, is entirely up to us. Once this deception is exposed, we realise that video games are not complete games: they are tools, toys with certain mechanics/affordances, allowing us to potentially create an infinite number of different games (or metagames) with our own infinite variations of rules.

Viewing video games as tools for metagames rather than as finished products dissolves the boundaries between game creators and players. It reframes the history of video games as something other than the passive consumption of products handed down from above. Studying plundercore, plunderludics, and the entire dimension of metagaming is therefore essential today to understanding video games—an integral part of our digital lives—beyond the capitalist cycle of production and consumption.

Matteo Lupetti

Matteo Lupetti writes about art criticism, digital art and video games in publications such as Artribune and Il Manifesto and abroad. He has been on the editorial board of the radical magazine menelique and the artistic direction of the reality narrations festival Cretecon. His first book is ‘UDO. Guida ai videogiochi nell’Antropocene’ (Nuove Sido, Genoa, 2023), a reinterpretation of the video game medium in the era of climate change and within the new multidisciplinary paths that foreground the non-human and its agency.