Internet is Broken, and It’s Up to Us to Fix It. Valerio Bassan’s Manifesto

by Alessandro Mancini

The original promise of the Internet—a free and open space for aggregation and democratic participation—has been betrayed. This is the central thesis of the essay Rebooting the System: How We Broke the Internet and Why It’s Up to Us to Fix It by journalist and media and technology consultant Valerio Bassan, published by Chiarelettere in 2024.

In the book, the author reconstructs the capitalist processes, such as privatization, gentrification, and commercialization, that have turned the Internet into an increasingly uninhabitable space controlled by a few dominant players. However, throughout his analysis, the journalist also presents scenarios and experiments that inspire hope for a better future for the Internet, emphasizing that “The future is not inevitable, but it’s up to us to ensure it is different from the recent past.”

Bassan also runs a weekly newsletter, Ellissi, which focuses on innovation, media, and digital topics and has over 18,000 subscribers. He is also the co-director of DIG, Europe’s most important festival dedicated to investigative journalism.

In this interview, we retrace some of the milestones and causes that led to the system’s breakdown as we know it, as well as the potential solutions for rebuilding a more sustainable and equitable Internet. This includes challenging the unfair business models that currently govern the web and emerging technologies.

The book was born out of the need to understand how the economic dynamics of the Internet have profoundly impacted key sectors like journalism, reducing their sustainability and independence.

“Journalism is in crisis because it cannot sustain itself in a context dominated by business models based on data collection and advertising. As I delved deeper into the topic, I realized that the problem is much broader and involves the very structure of the Internet,” explains Bassan.

According to the author, the initial idea of a free and open Internet has been betrayed by three main factors: privatization, commercialization, and centralization of power. Starting in the 1990s, with the opening of the Internet market in the United States, online advertising became the primary form of monetization.

“This apparent free access comes at a hidden cost: our attention and our data,” Bassan points out. Major tech platforms have shaped the digital ecosystem, creating monopolies that limit competition and impose rules in their favor.

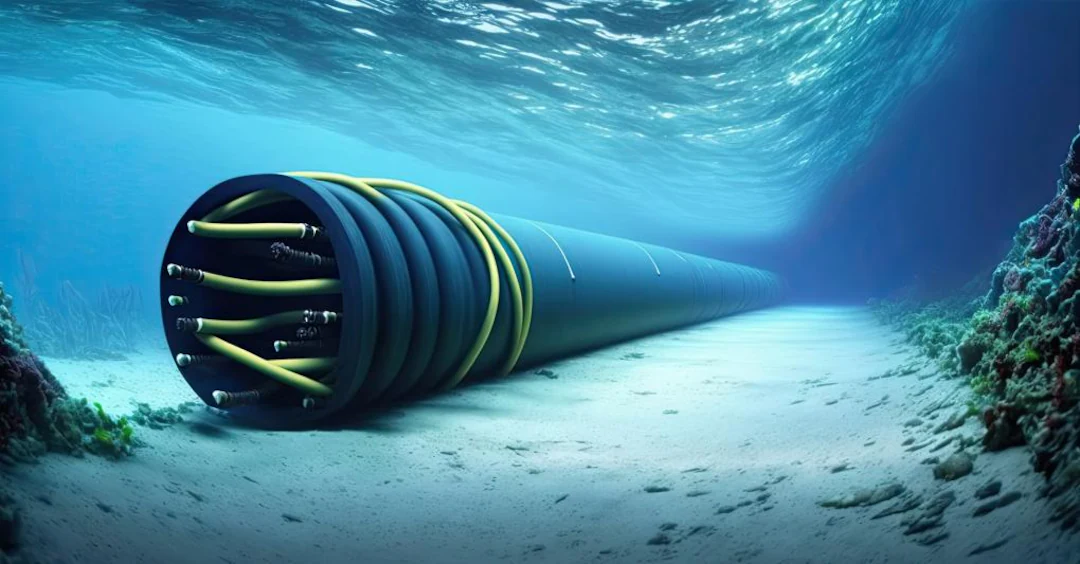

A concrete example of the importance of network infrastructure is Cuba’s so-called Paquete Semanal—a weekly collection of offline digital content, assembled by Cuban exiles and physically distributed on the island via USB drives and hard disks. This system allows Cubans to access content otherwise unavailable due to the lack of high-speed networks and high costs.

“The Cuban case highlights how control over the physical infrastructure of the Internet, such as undersea cables, is crucial: those who own them can control the flow of information and influence entire countries,” warns Bassan.

The importance of solid and accessible infrastructure is not limited to countries like Cuba. Even in Western nations, the control of large corporations over networks is an increasingly debated issue. The spread of satellite networks, for instance, raises questions about how Internet access can be influenced by private interests and geopolitical dynamics. The management of infrastructures by giants like Meta, Google, and Amazon poses a threat to the digital sovereignty of countries and limits equitable access to the Internet.

The author often uses metaphors to make complex phenomena understandable. One example is Berlin, a city he lived in during a period of intense urban and technological transformation. “Berlin has become a symbol of digital gentrification: just as working-class neighborhoods were transformed by the arrival of wealthier new residents, the Internet has been monopolized by a few economic actors, making ‘online life’ more expensive and less inclusive.” In Berlin, protests against Google Street View revealed strong resistance: many citizens requested and obtained that their homes be blurred from digital maps. This was an example of collective resistance against privacy invasion.

The parallels between urban and digital transformations don’t stop there. Bassan points out how platformization has changed the dynamics of digital communities that were once autonomous and free. Independent forums and blogs have been gradually replaced by commercial platforms that monopolize users’ attention and set the rules of the game. “Algorithmic personalization has transformed the Internet into a space where we are increasingly passive users and less active creators,” the author emphasizes.

The centralization of the Internet also resurfaces in the recent evolution of Web 3.0. “Technologies like blockchain, cryptocurrencies, and NFTs have reopened the debate on decentralization, but they often end up replicating the mistakes of the past. Even in the cryptocurrency world, power dynamics favor those with more resources,” explains Bassan. The risks of power concentration in the hands of a few operators remain high, and even some promises of innovation, such as decentralized protocols, risk being exploited for speculative purposes.

Meanwhile, big tech companies continue to colonize new technological frontiers, such as the metaverse and artificial intelligence.

“Facebook’s rebranding as Meta is a glaring example: an attempt to control even the digital future.” The issue of generative AI represents a new challenge. While Bassan acknowledges AI’s positive potential, he warns against underestimating its risks. “Many generative AI models are black boxes, opaque to end users. It is essential to establish clear rules to prevent discrimination and ensure transparency,” he states. The growing concentration of technological power in the hands of a few companies raises questions about responsibility and ethical limits in AI development.

“Algorithmic personalization has transformed the Internet into a space where we are increasingly passive users and less active creators.”

Bassan provides examples of how artificial intelligence is already influencing journalism, generating automated content but also undermining source control and the accuracy of information. “If we allow algorithms to decide what is news and what isn’t, we risk losing the diversity of perspectives,” he warns. According to the author, technological progress should not be opposed, but it must be managed responsibly.

Despite everything, the author sees a positive signal: “Today, there is a more open and participatory debate on these issues, which gives us the opportunity to act before it’s too late.” Bassan emphasizes the importance of a collective approach: regulating AI, promoting open-source innovation, and raising awareness among users are crucial steps to ensure a more equitable digital future.

The author also offers practical advice for inhabiting the Internet more sustainably. The first step is information: “You don’t need to be an expert to understand how network infrastructure works and how our data is used.” Educating oneself about tracking mechanisms and understanding which platforms collect our data is essential for making more informed choices.

The second piece of advice is to adopt more ethical alternative tools: “Browsers like Brave and Firefox respect user privacy more. Changing app settings to limit data collection is also an important step.” Avoiding overly invasive services and adopting open-source solutions can reduce the influence of major platforms on our personal data.

Finally, he encourages active participation: “Talking about these issues, reading books, and joining public debates are essential for building collective awareness.” Promoting more widespread digital literacy means contributing to a public discourse that views the Internet as a common good and not just a consumer marketplace.

In the book, Bassan also cites the research of political scientist Erica Chenoweth, which shows that every revolution has succeeded when at least 3.5% of the population supported the change. “Not everyone needs to participate, but a critical number is enough to influence policies and reverse course,” he notes.

The author concludes with a call to action: “We must leave future generations with a better Internet than the one we have today. The network is a valuable resource, but only if we make it a more equitable and democratic space.”

Alessandro Mancini

Graduated in Publishing and Writing from La Sapienza University in Rome, he is a freelance journalist, content creator and social media manager. Between 2018 and 2020, he was editorial director of the online magazine he founded in 2016, Artwave.it, specialising in contemporary art and culture. He writes and speaks mainly about contemporary art, labour, inequality and social rights.