In China, artificial intelligence brings the dead back to life

Many Chinese companies are venturing into the creation of “griefbots,” digital avatars of deceased loved ones.

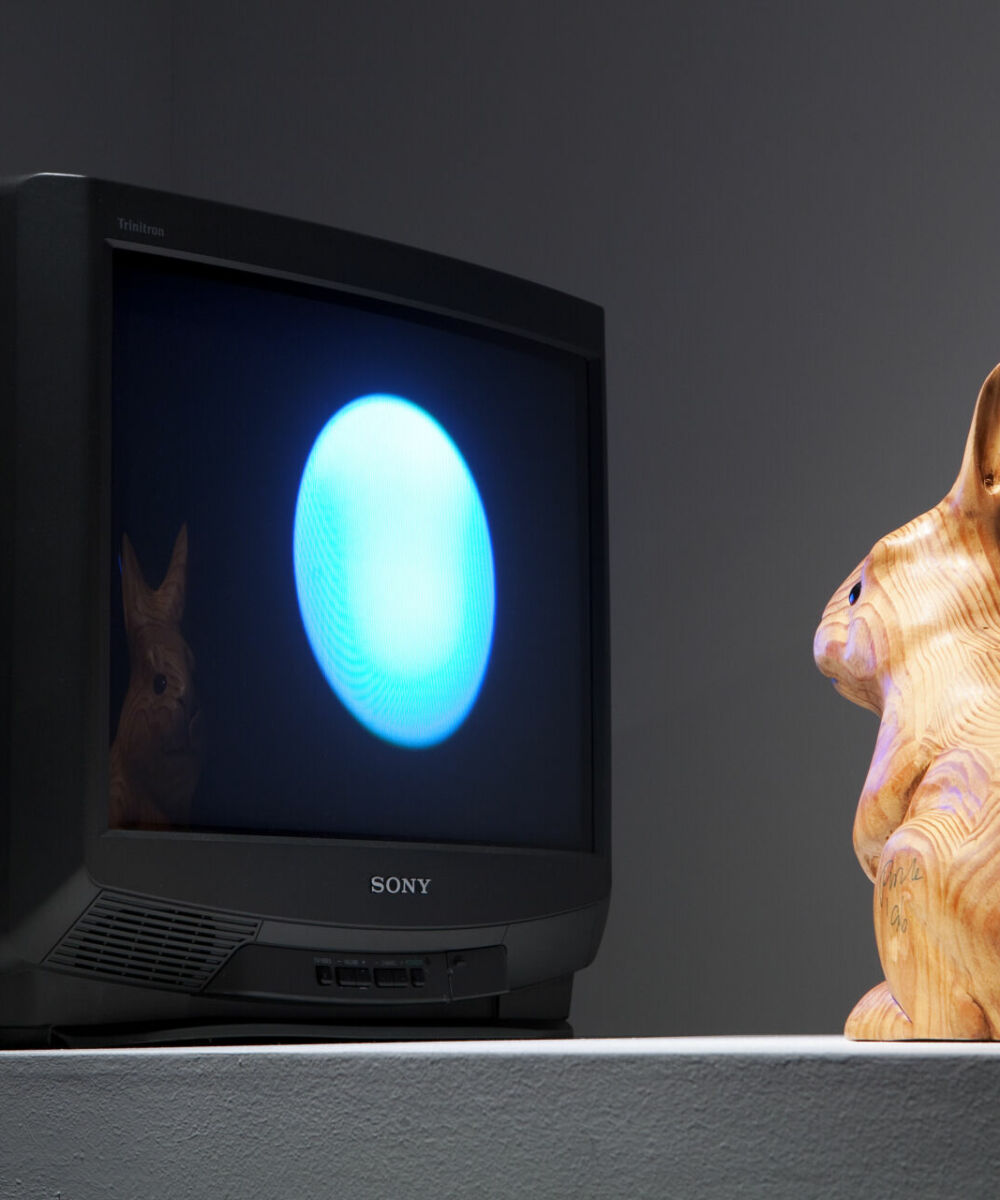

In 2013, the second season of the acclaimed British series Black Mirror, in the episode Be Right Back, envisioned a service that allowed people to continue communicating with their deceased loved ones. In the series, this was achieved not through a medium or paranormal phenomena but by using the data left online by the deceased to create a digital avatar. In recent years in China, this concept has moved from science fiction to reality, thanks to the development of an industry dedicated to processing grief through digital connection experiences.

One of the pioneers in this field is Yu Jialin, a young computer engineer from Hangzhou. Driven by the desire to see his grandfather, who had passed away ten years earlier, Yu explored the potential of Artificial Intelligence (AI) to make his dream a reality. His research led to the development of a griefbot—a digital system designed to replicate the distinctive traits of a deceased individual. Tools like ChatGPT and other generative AI technologies have paved the way for griefbots, offering personalized experiences that simulate authentic conversations. These programs analyze existing data to reconstruct aspects of the deceased’s personality, providing comfort to the bereaved. Some griefbots can even evolve over time, adapting to new information shared by users, effectively becoming a continuously growing digital presence.

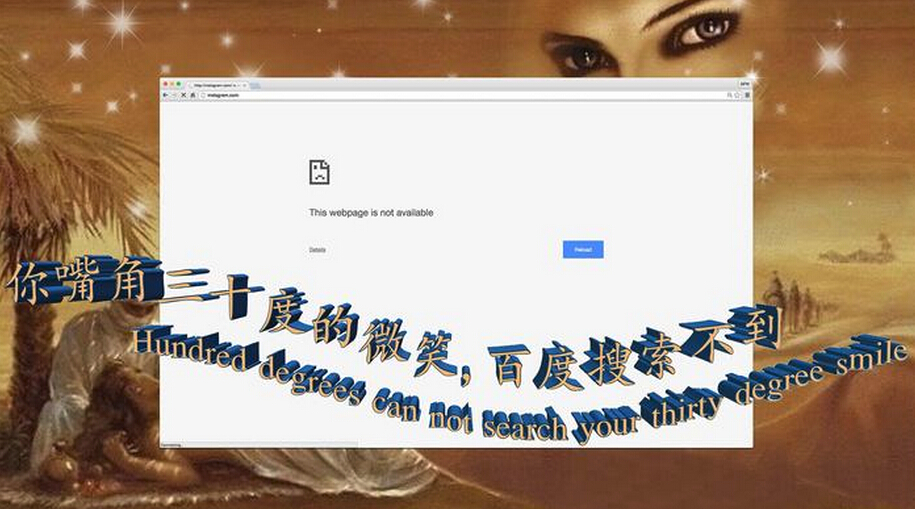

Several Chinese tech companies are diving into this emerging field. Much like in Black Mirror, all they require are the “digital memories” of the departed to bring them back digitally. Fragments of a person’s life—messages, videos, audio, and images—can be used to “feed” language models capable of accurately reproducing the loved one’s voice, behaviors, and communication style.

One such company is Super Brain, an AI studio based in Taizhou. Its founder, Zhang Zewei, shared in an interview with the magazine Sixth Tone: “It all started with a father who wanted to use artificial intelligence to connect with his son, who had died in a car accident.” These digital avatars are not mere simulations but realistic recreations. Their products range from audio and video clips to interactive chatbots. In 2023 alone, Super Brain completed over 400 orders, primarily for individuals seeking to commemorate deceased relatives. While a short video clip costs a few hundred yuan, a custom chatbot can range from 50,000 to 100,000 yuan (approximately $6,860–$13,710).

These digital avatars are not mere simulations but realistic recreations. Their products range from audio and video clips to interactive chatbots.

While these digital avatars provide significant comfort to those grieving a loss, they also raise several concerns and ethical questions. Excessive reliance on such technologies could interfere with the natural grieving process, potentially leading to emotional dependency. Moreover, there is the risk of misuse and possible violations of the memory and dignity of the deceased.

This sector has found particularly fertile ground in China, partially due to Confucian cultural roots. In Chinese tradition, connections with ancestors remain a vital part of daily life, with the veneration of deceased loved ones being a cornerstone of Confucian values. Festivals such as Qingming—the Chinese equivalent of All Souls’ Day in November—are a testament to this. Held around April 4 or 5, the occasion sees millions visiting the graves of loved ones to clean them, decorate them, and offer symbolic tributes of food and money to the departed. Despite the strong rituals tied to physical locations, such as graves and urns, technology appears poised to redefine how people connect with their ancestors. In many Chinese homes, where altars dedicated to ancestors are common, digital avatars might soon find a place, bridging tradition and innovation.

The final episode of Be Right Back does not, however, end on a positive note. Without giving away too many spoilers for those who haven’t seen the series, one can only imagine the consequences of becoming emotionally dependent on a digital entity that, while identical to the deceased in voice, mannerisms, and memories, cannot fully replace the absence of a loved one.

Camilla Fatticcioni

China scholar and photographer. After graduating in Chinese language from Ca’ Foscari University in Venice, Camilla lived in China from 2016 to 2020. In 2017, she began a master’s degree in Art History at the China Academy of Art in Hangzhou, taking an interest in archaeology and graduating in 2021 with a thesis on the Buddhist iconography of the Mogao caves in Dunhuang. Combining her passion for art and photography with the study of contemporary Chinese society, Camilla collaborates with several magazines and edits the Chinoiserie column for China Files.