NET ECOLOGY

Digital Worldbuilding: Ecological Dreams and Escapist Illusions

di Laura Cocciolillo

Digital worldbuilding—the creative practice of designing and constructing virtual worlds using technologies like virtual reality, augmented reality, 3D simulations, and other immersive platforms—represents one of the most fascinating frontiers of contemporary art. It is a space where technology and creativity merge to shape “new possible worlds.” Through virtual settings, imaginary landscapes, and immersive narratives, artists explore themes crucial to our time: environmental sustainability, the human-nature relationship, and the potential for harmonious coexistence with the planet.

The core idea of “ecocritical” worldbuilding is that imagination—or rather, the ability to conceive new ecological scenarios—is a fundamental exercise in shaping our future. However, this practice raises fundamental questions: Is it truly an effective means of fostering critical reflection on our ecological impact, or is it merely a rhetorical experiment, even an act of escapism, offering a way to evade the difficulties of reality without proposing real solutions?

Jakob Kudsk Steensen and the “Nature-Tech” Imagination

A quintessential example is the work of Jakob Kudsk Steensen, an artist and director who uses virtual reality to create hypnotic digital environments inspired by biodiversity and natural ecosystems. His project Re-Animated is a poetic and technological journey that digitally reconstructs an extinct bird species, the Kaua’i ‘ō‘ō, weaving together 3D scans, recorded sounds, and immersive simulations. The work invites viewers to reflect on the fragility of ecosystems and the need to preserve biodiversity.

Steensen’s approach is notable for how it leverages technology to amplify an emotional connection with nature, prompting audiences to consider their role within a broader ecological network. “We are often trapped in our patterns of thought,” Steensen explained to me a few years ago, “without questioning the deeper roots of our beliefs and behavior patterns, simply reacting to or expressing them. Worldbuilding allows us to engage with deeper ethos, ideologies, and belief systems because in these worlds, values can take any form. The causes and effects of actions, whether social or environmental, can be explored playfully.”

Yet, one might argue that immersion in digital worlds offers aesthetic gratification that risks replacing concrete action. Indeed, Steensen clarifies: “I think there is a big difference between a more explicitly scientific or activist approach to climate issues and what I do as an artist. It’s connected, but ultimately, I want people to feel and question what it means for them to live in a rapidly changing world.” The underlying question remains: Do such experiences lead to real changes in the daily behaviors of those who engage with them, or do they remain confined to passive contemplation?

Marshmallow Laser Feast: Technology for Expanded Sensory Experiences

Another significant example is Marshmallow Laser Feast (MLF), a collective exploring the intersections of art, science, and technology. Their work Treehugger is a VR installation that allows viewers to “become” a tree, experiencing the internal processes of photosynthesis and the flow of nutrients. By combining LiDAR scans, graphic simulations, and binaural sound, MLF transforms our relationship with nature into a multisensory experience that fosters a new sense of empathy and connection.

Digital worldbuilding has the potential to redefine our relationship with the planet, offering alternative visions and fostering critical reflection.

In this case, the ecological impact of the work seems clear: to inspire awe and respect for nature, encouraging viewers to consider their relationship with the natural world more deeply. However, even here, criticism arises that such experiences may be perceived more as entertainment than a call to action. When I asked Barney Steel, co-founder of the collective, whether his installations could truly enhance empathy for nature and animals, he dispelled some doubts, saying: “I think of empathy and relationships as being the same thing: for example, if I have a dog, of course, I wouldn’t eat it… but why do I care about my dog and not someone else’s? It’s because we are connected through all the experiences we’ve shared. And this happens because bonds are not formed based on what we don’t see or perceive but through what we experience firsthand. Probably, if we lived in a society where we had direct contact with everything we consume, we’d live better.”

Ideally, therefore, offering viewers a firsthand experience through virtual reality could nurture this bond rooted in lived experience. However, empathy itself is not scientifically measurable, so we cannot assess its increase or the concrete impact of the experience.

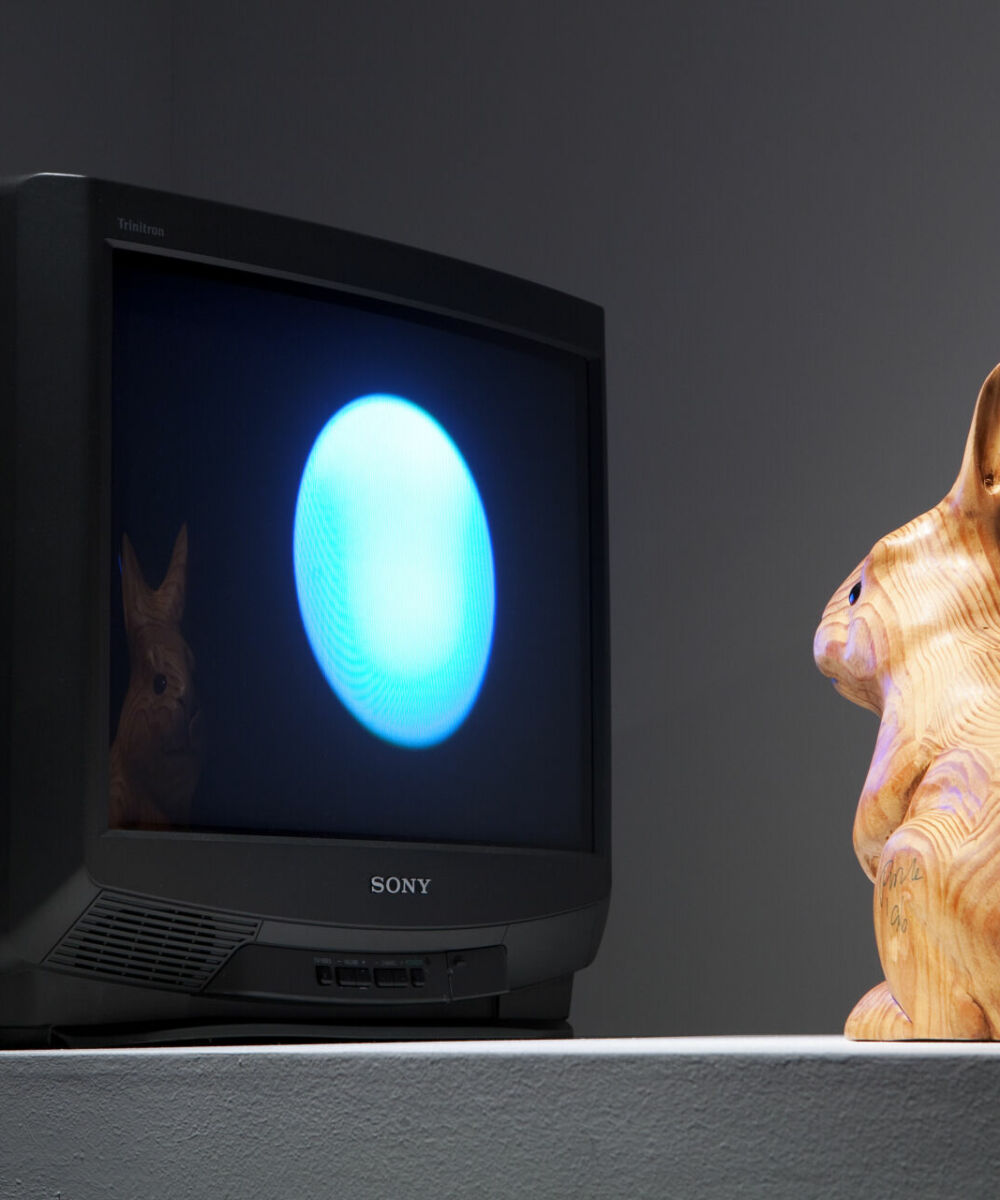

Worldbuilding Between Utopia and Escapism

When addressing ecological themes, digital worldbuilding operates on a delicate balance between the aesthetic construction of a utopia and the illusion of an escape from the world we have irreversibly damaged. On the one hand, it offers visions of an alternative future that can stimulate rethinking our lifestyles and consumption patterns. On the other, it risks becoming a form of escapism, a comforting illusion that does not demand real commitment to addressing present problems.

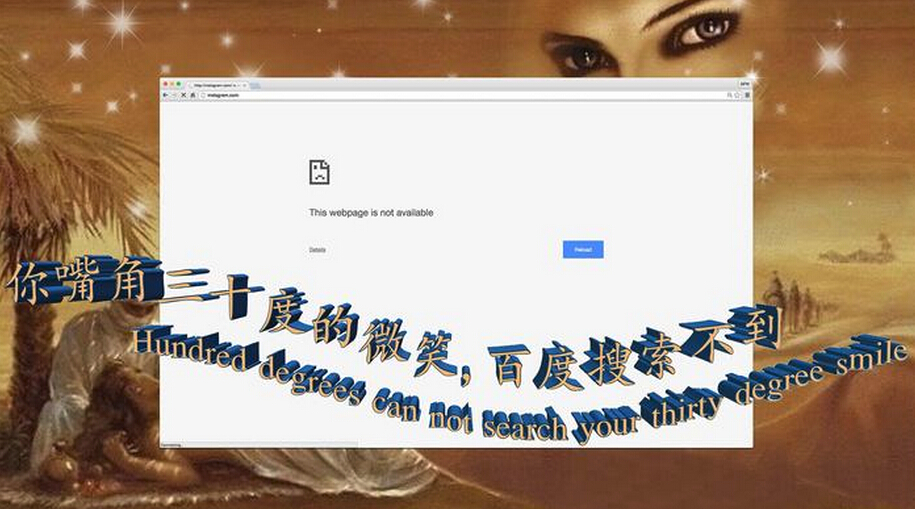

Adding to this is the environmental impact of the technologies used for digital worldbuilding. Creating virtual worlds requires significant computational resources and energy consumption—a paradox that often contradicts the sustainability messages conveyed by these works.

Moreover, the accessibility of these experiences is another point of reflection. Most digital worldbuilding works—often only accessible through virtual reality headsets—remain confined to museum spaces or art galleries, limiting their potential reach and engagement with a broader audience. If the goal is to raise awareness and promote global change, it is essential to consider ways to make these experiences more inclusive and accessible.

Digital worldbuilding has the potential to redefine our relationship with the planet, offering alternative visions and fostering critical reflection. However, its actual impact depends on several factors: the accessibility of the works, their ability to translate into concrete actions, and artists’ awareness of the limitations and contradictions of the technologies they use. While the risk of escapism is ever-present, these practices can also inspire new collective narratives capable of guiding us toward a more sustainable future.

Laura Cocciolillo

Is an art historian specialising in art and new technologies and new media aesthetics. Since 2019 she has been collaborating with Artribune (for which she is currently in charge of new media content). In 2020 she founded Chiasmo Magazine, an independent and self-funded Contemporary Art magazine. From 2023 he is web editor for Sky Arte, and from the same year he takes care, for art-frame, of the column ‘New Media’, dedicated to digital art.