NET ECOLOGY

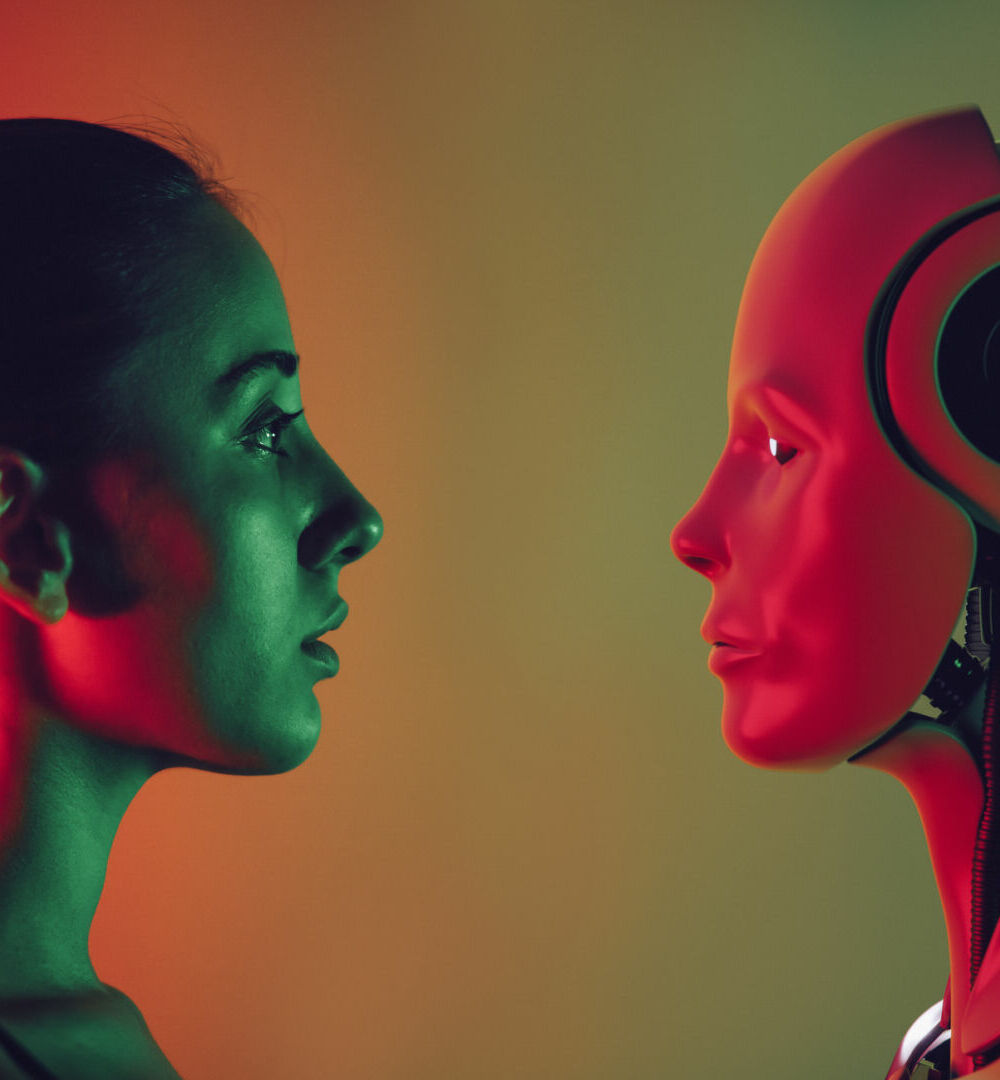

Cyborg Ecology: Rethinking the Body (and the Human) in the Age of Technological Symbiosis

di Laura Cocciolillo

In a world made hostile by the acceleration of production processes and industrial and digital development, technological progress seems not only to be the cause of growing environmental instability but also the sole possibility for survival. Human agency has irreversibly altered ecosystems, leading to the collapse of entire habitats, and in this process, humanity has transformed itself, its own identity, gradually (and sometimes unconsciously) hybridizing with technology to the point where there is no return. What might seem like science fiction is already a reality: the “human-technology symbiont” is the result of a process that has escaped our control, remaining the only viable option for reconstructing reality.

In this context, we find the exhibition Bloodchild. Scenes from a Symbiosis, curated by art critic Domenico Quaranta at the Fondazione Spazio Vitale in Verona. Open until November 16, the exhibition gathers the works of four artists who, through diverse approaches and media, explore the “symbiotic relationship between humans and technology, and how this alliance is simultaneously functional and dysfunctional, brings both benefits and suffering, enhances certain limbs while atrophying others, and requires a constant renegotiation of the agreement,” explains the curator. The very title, Bloodchild, evokes an organic, visceral, and unsettling fusion: a body that transforms, that absorbs external elements yet becomes a mutant hybrid in the process.

Ecology emerges as a persistent underlying theme, inevitably intertwining with cyborg feminist theories that marked the third wave of feminism. Eco-critical thought and reflections on the hybridized body trace their roots back to Donna Haraway’s Cyborg Manifesto (1991), a seminal text that profoundly influenced contemporary thought on the body, technology, and our relationship with nature. It proposes a radical break with traditional dichotomies between natural and artificial, human and machine, male and female. The cyborg, a hybrid and subversive figure, embodies this fusion, rejecting binary divisions between natural and technological: for Haraway, the key to transcending the synthetic-organic dichotomy lies in recognizing that technological systems are inseparable from the web of life, becoming part of a larger ecosystem in which the interaction between species, machines, and the environment is deeply interconnected.

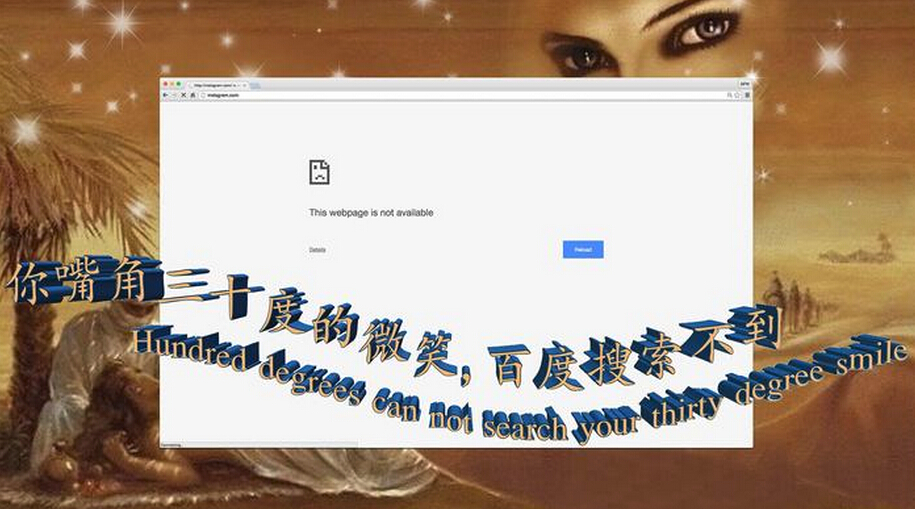

In this exhibition, such perspectives are conveyed through the work of Lynn Hershman Leeson, whose practice explores the boundary between body and technology through a feminist and cyborg lens. Her cult film Teknolust (2002) examines alternative reproductive systems, another pivotal element in Haraway’s feminist ecocriticism. In the film, biogeneticist Rosetta Stone, played by Tilda Swinton, clones three versions of herself by embedding her DNA into an artificial intelligence program. Here, biotechnology is not merely a reproductive tool but a medium for probing the potential fusion between the biological and the technological: the cloned body becomes an ecosystem in itself, interacting with both the natural and technological worlds, challenging the notion of a “natural body” as something distinct and separate from its environment.

Quella che sembra fantascienza è già realtà: il “simbionte umano-tecnologia” è il risultato di un processo che, sfuggito al nostro controllo, resta l’unica opzione per ricostruire il reale.

Ecology, within cyborg theories, does not concern only the preservation of nature in a narrow sense but extends to a post-anthropocentric vision in which the boundaries between human, animal, and machine dissolve. From this perspective, the human future—or post-human future—can no longer be imagined as a subject separate from the rest of the ecosystem, but as an integral part of a complex web of relationships that include the technological and the non-human. Within this framework, symbiosis is not merely a metaphor but an emerging reality, urging us, through artists like Leeson, to observe it.

As Quaranta notes, “the environment remains somehow in the background, yet ecological thought permeates nearly every work, in a more or less visible form, because symbiosis does not happen in a void.” The rethinking of humanity’s bond with technology necessarily takes place both at the identity level—by examining human transformation—and at the environmental level, by investigating the ecological consequences and potential scenarios to which humans, due to their impact on ecosystems, will need to adapt, likely with an increasingly essential reliance on technology. From these post-human, sometimes post-apocalyptic scenarios arise the “monsters” halfway between the biological and the virtual, as seen in Sahej Rahal’s work. In Druj, for example, a synthetic generative entity responds to ambient sounds, effectively symbolizing the inherently relational nature of being, which shifts according to interactions with other agents and the environment. As feminist and eco-critical quantum theory by physicist Karen Barad suggests, every agent with agency is indeed “co-constituted” reciprocally (that is, it both “takes shape from” and “shapes” what surrounds it).

We find similarly strange (living?) “prosthetic” beings, as Quaranta calls them, in the work of Ivana Bašić. In Belay My Light, the Ground Is Gone, a fragile marble alien sculpture “lives in its environment, not only because its delicate balance conceals an ongoing state of tension but because the process it represents generates waste (marble dust) that dynamically inhabits the space.”

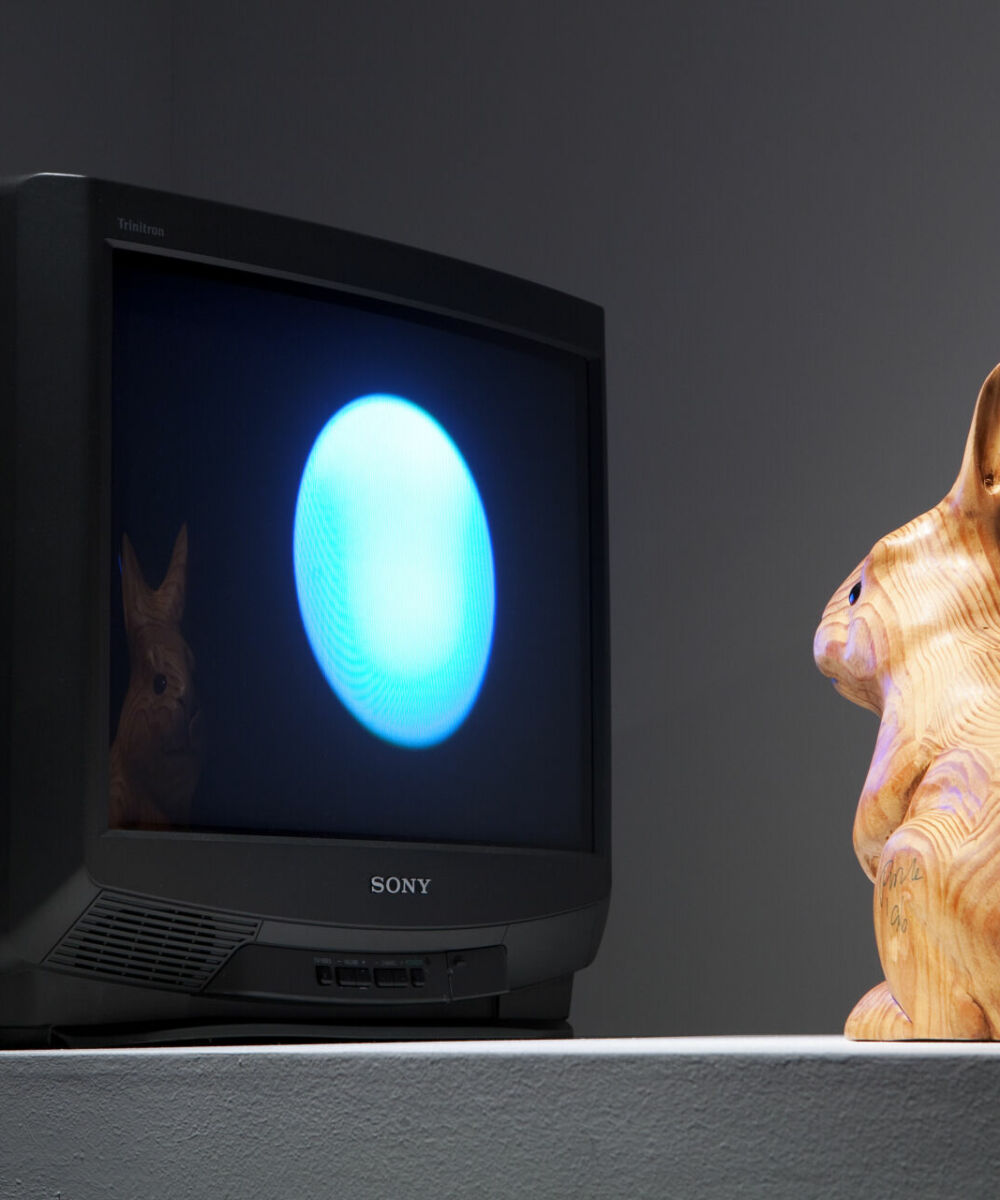

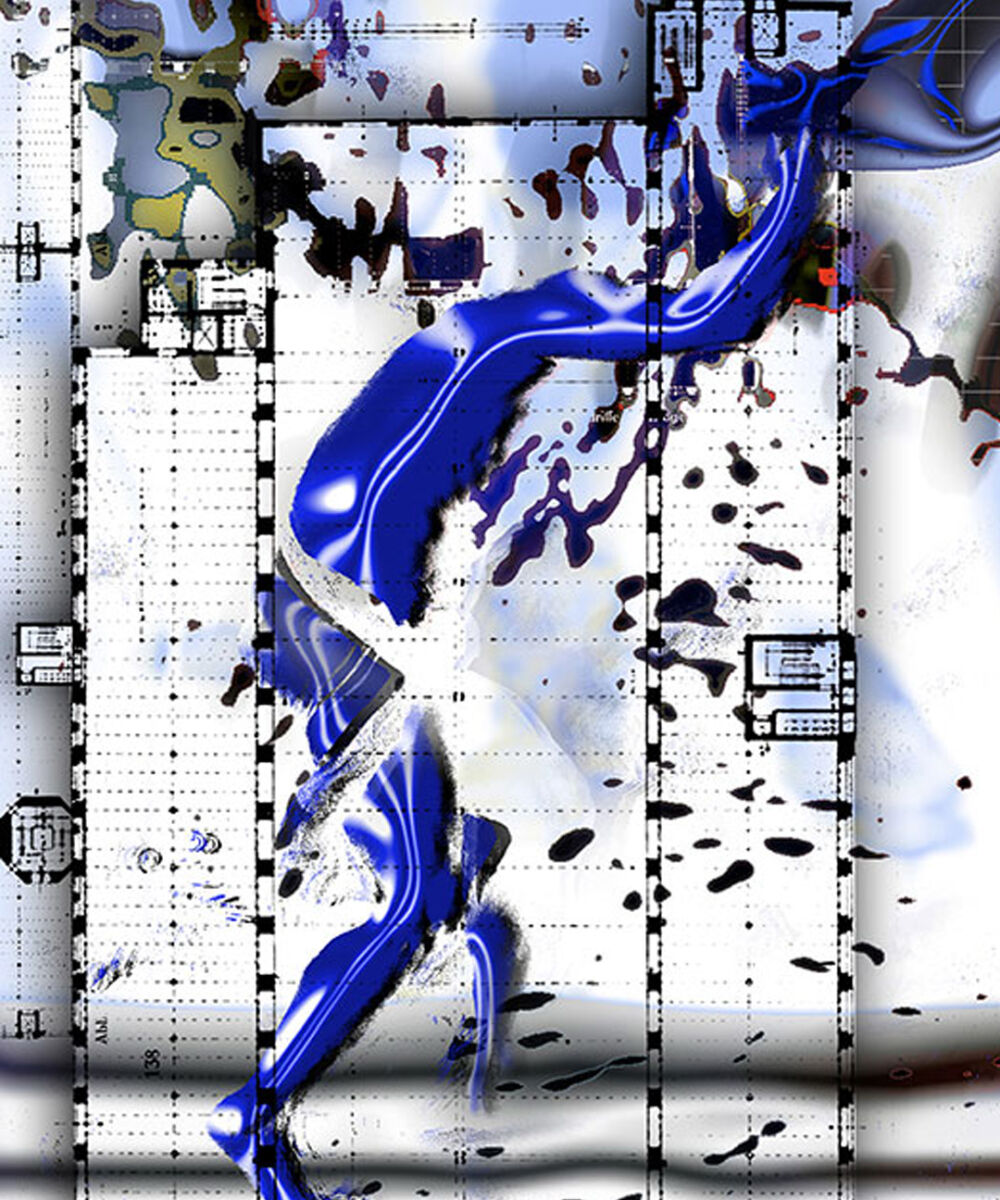

Finally, Oliver Laric’s work returns us to the inevitable interconnection and intra-action governing and linking all agents that compose reality, prompting us to step down from the self-imposed pedestal of anthropocentrism. His looping video Exoskeleton, through a morphing-like sequence at a hammering rhythm, transitions from one natural form to another, showing us “how the life of forms and biological life are governed by the same logic, finding continuity in an unceasing succession of copies and variations, duplicates and discards, reproductions and grafts,” emphasizes Quaranta.

In conclusion, technology is not an invention foreign or external to the human being, but a continuation of processes already present in nature. Conversely, as new media theorist Jussi Parikka teaches, natural and biological reality is already inherently technological. Everything that makes up reality is bound in a co-constituting relationship, necessarily transcending binary thinking. Our aversion or wonder at recognizing the connection between organic and synthetic, natural and artificial, arises from a tendency to think in binary oppositions, separating what we consider natural from what we define as artificial. Recognizing that technology is inherent in natural forms and that the boundaries between these worlds are permeable allows us to embrace a more integrated, fluid vision of our existence, where symbiosis and co-evolution become the keys to facing contemporary (and future) challenges.

Laura Cocciolillo

Is an art historian specialising in art and new technologies and new media aesthetics. Since 2019 she has been collaborating with Artribune (for which she is currently in charge of new media content). In 2020 she founded Chiasmo Magazine, an independent and self-funded Contemporary Art magazine. From 2023 he is web editor for Sky Arte, and from the same year he takes care, for art-frame, of the column ‘New Media’, dedicated to digital art.