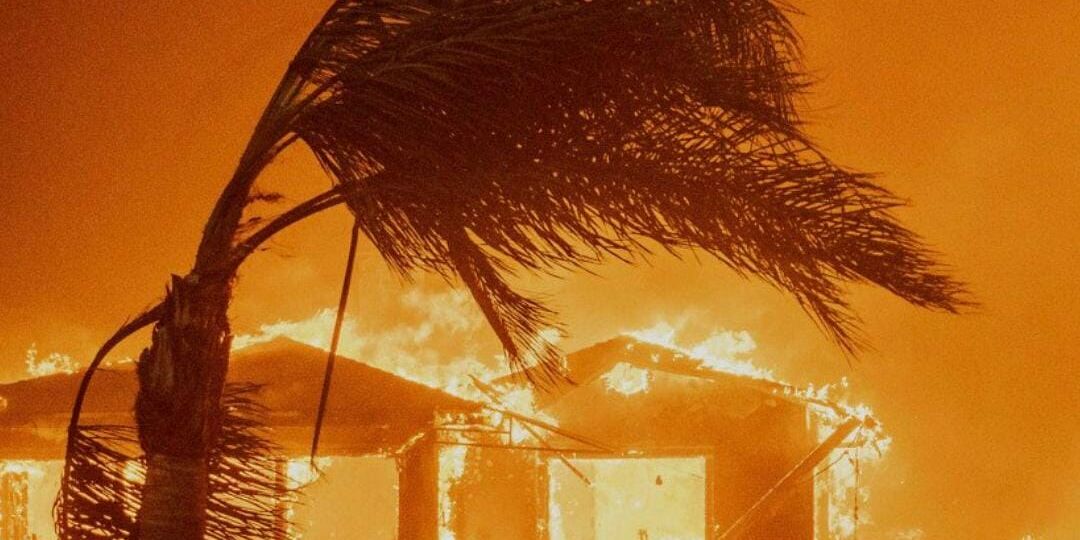

Between real flames, real wars, and digital filters, we cannot agree on the right or wrong way to post about pain online—forgetting that social media are structurally ambiguous platforms, just like us.

Recent news has reported Donald Trump’s decision to introduce a list of “banned” words—terms that should no longer appear, or should be significantly reduced, in official documents in order to align with his political vision.

Metagames are games built upon other games. However, according to LeMieux and Boluk, in reality, “metagames are the only kind of games that we play.” Every game is situated within a context that influences and alters it, creating a metagame that we ultimately play, and every game becomes part of an assemblage of human and non-human agents, integrating into complex systems that can never be fully comprehended.

Redazione THE BUNKER MAGAZINE There’s a disarming paradox in Elon Musk’s ability to command attention, as though the magnate is…

Last Tuesday, Mark Zuckerberg, CEO of Meta, announced the end of the fact-checking programme on Facebook and Instagram. In its place, he stated, a system of “Community Notes” will be introduced, already trialled on X (formerly Twitter) under Elon Musk’s leadership. This decision, currently limited to the United States, has immediately drawn praise from Donald Trump and his entourage, marking what many observers view as a significant ideological realignment between Meta and the newly elected American president.

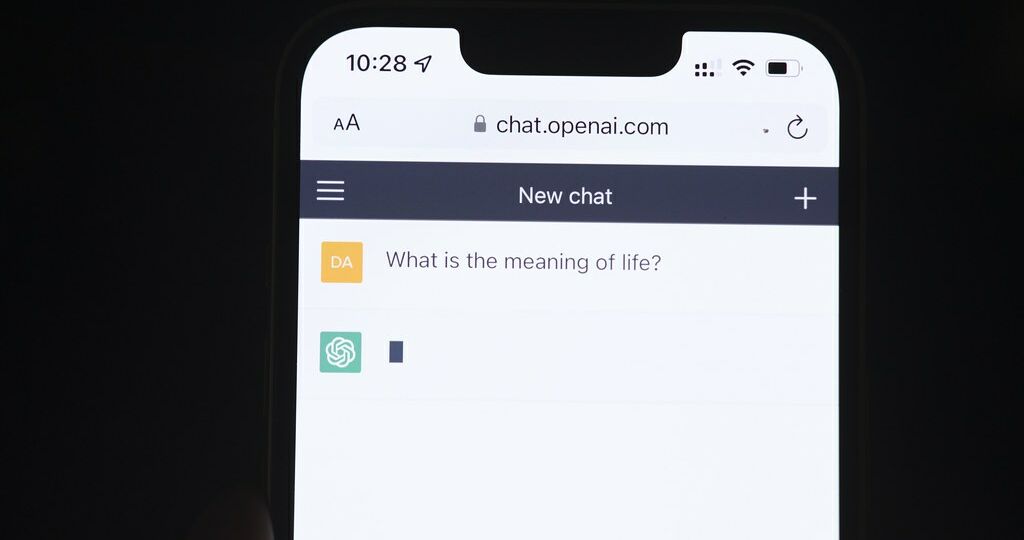

Not long ago, a case brought to public attention the potential negative impact of chatbots. Two parents sued an AI company after interaction with one of their chatbots allegedly led their children to imagine and discuss plans to kill them. The incident is undoubtedly unsettling, but it’s also reasonable to assume that such behavior might reflect pre-existing family and social dynamics — a doubt that seemingly did not cross the parents’ minds.

A brief history of the zeitgeist, or how ‘vibes’ went from being the emotional language of a close-knit community to fuelling an entire economy.

With these words, Neuromancer, William Gibson’s debut novel, opens. Published in 1984, this incipit remains so distinctive and unsettling that it feels as if it were written yesterday.

We live in strange times when it comes to social reactions. Once upon a time, adverse political events spurred protests and public demonstrations, but today, dissent and political disillusionment often find expression through other means.

Exiting the pandemic was like waking up in another era. Suddenly each of us had at our disposal artificial intelligences capable of solving complex problems, generating all kinds of images or even writing and interpreting songs.