Cao Fei: the Artist who describes the dystopic side of Digitalisation

by Camilla Fatticcioni

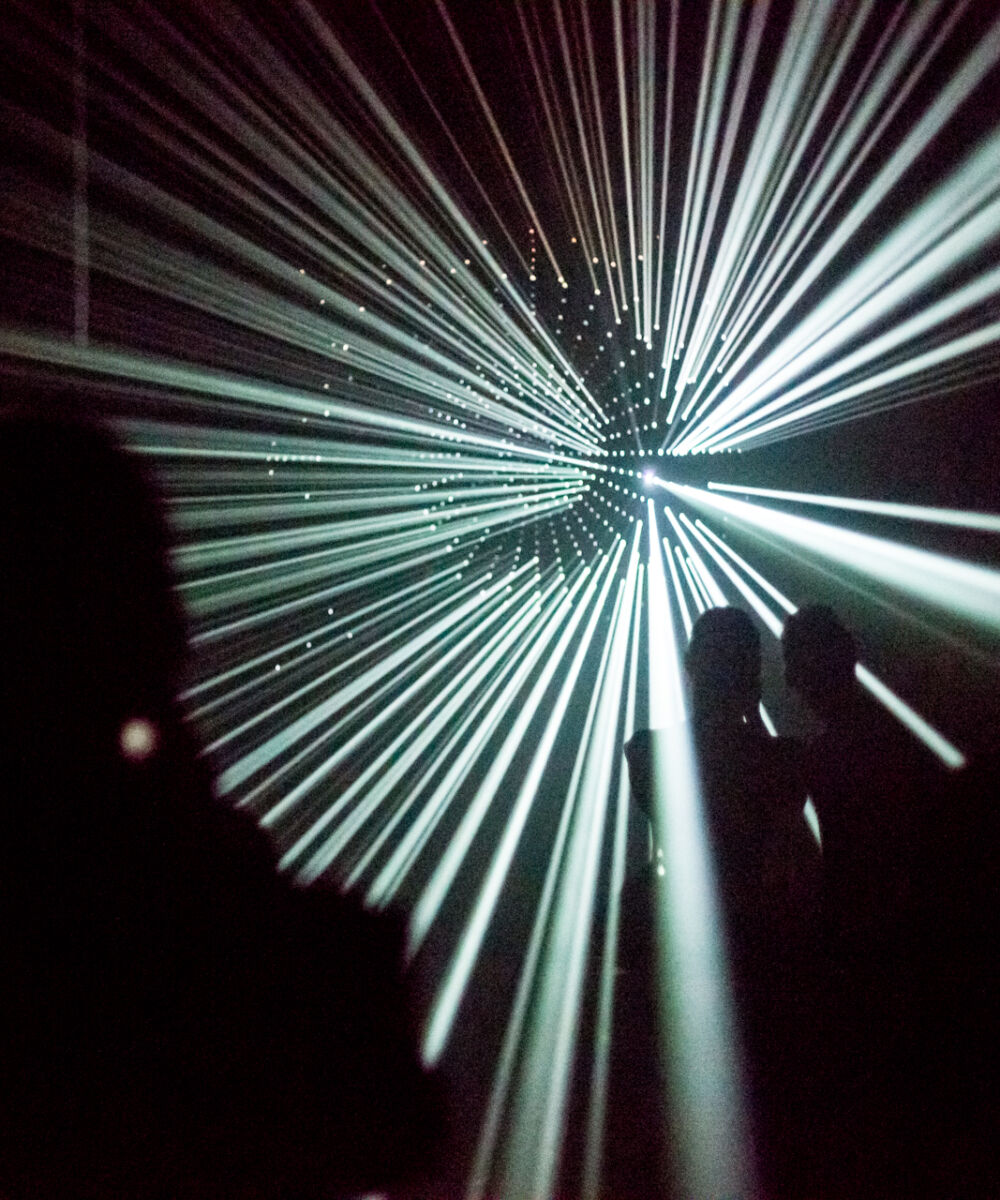

The future of digitalisation is dystopic, and it is already very close at hand. At least, this is the opinion of the Chinese multi-media artist, Cao Fei (Guangzhou, 1978). Cao Fei sees art not only as a social instrument, but also as assuming a prophetic role. In her films and installations, the artist combines social comments, popular aesthetics, and references to Surrealism: her works reflect the rapid changes underway in Chinese society today, including aspects brought about by the rapid digital development of the past twenty years.

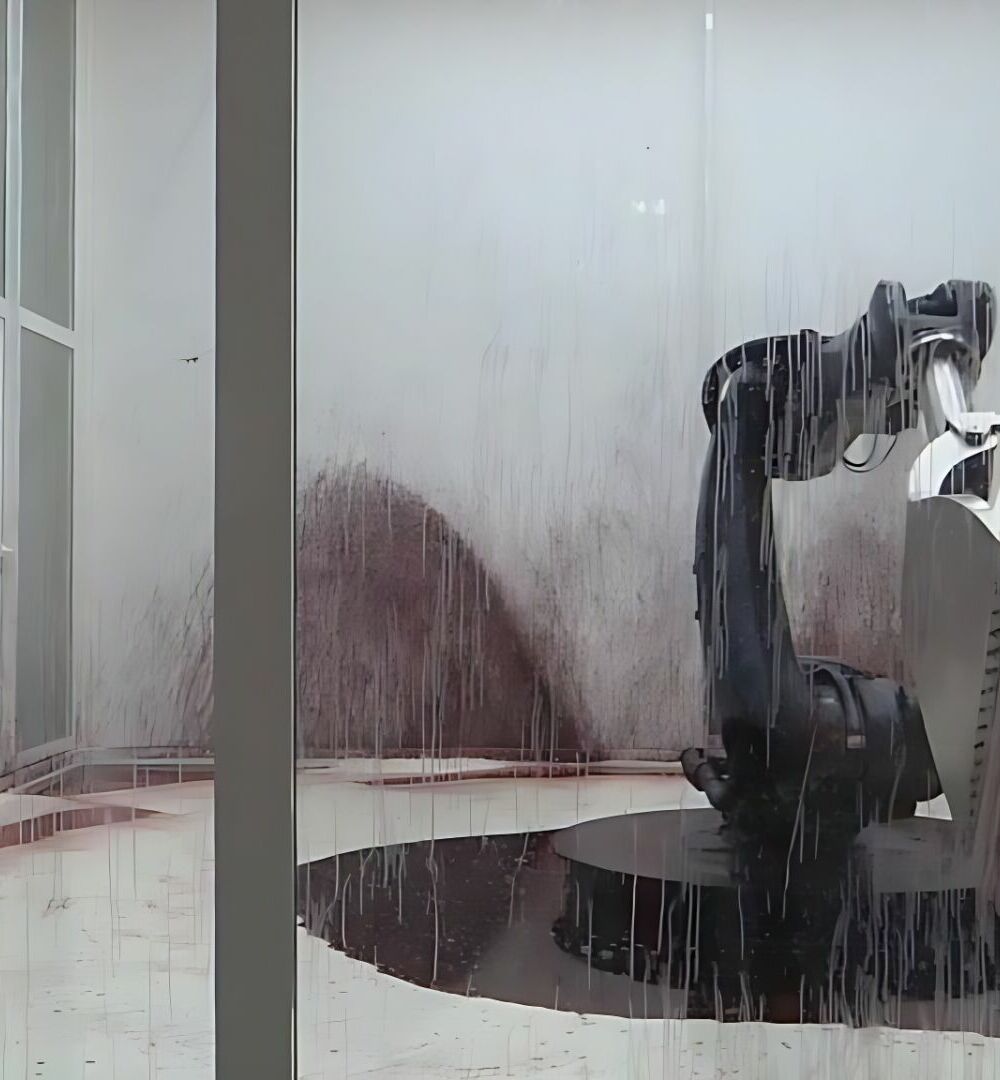

Born during the period of the Four Modernizations of Deng Xiao Ping, Cao Fei focussed her artistic production on an analysis of rapid Chinese industrial and economic development. Using digital instruments, video art, augmented and virtual reality, she has scrutinised the social consequences linked with rapid technological progress with a critical eye, able to place the viewer before a silent and invisible dystopic vision of the present. The artist very often speaks about the alienation of workers, as in her video work, Whose Utopia, in 2006, one of her most famous pieces, but she uses technology to her own advantage to investigate the limits of digital society. In Whose Utopia, Cao Fei filmed daily activities in a light bulb factory, highlighting the mechanised tasks carried out by the workers, also interviewing them on the reasons that led them to work in that job. Alienation remains a central theme in her artistic research, which in recent years, has been focussed on the effects of digitalisation in our society.

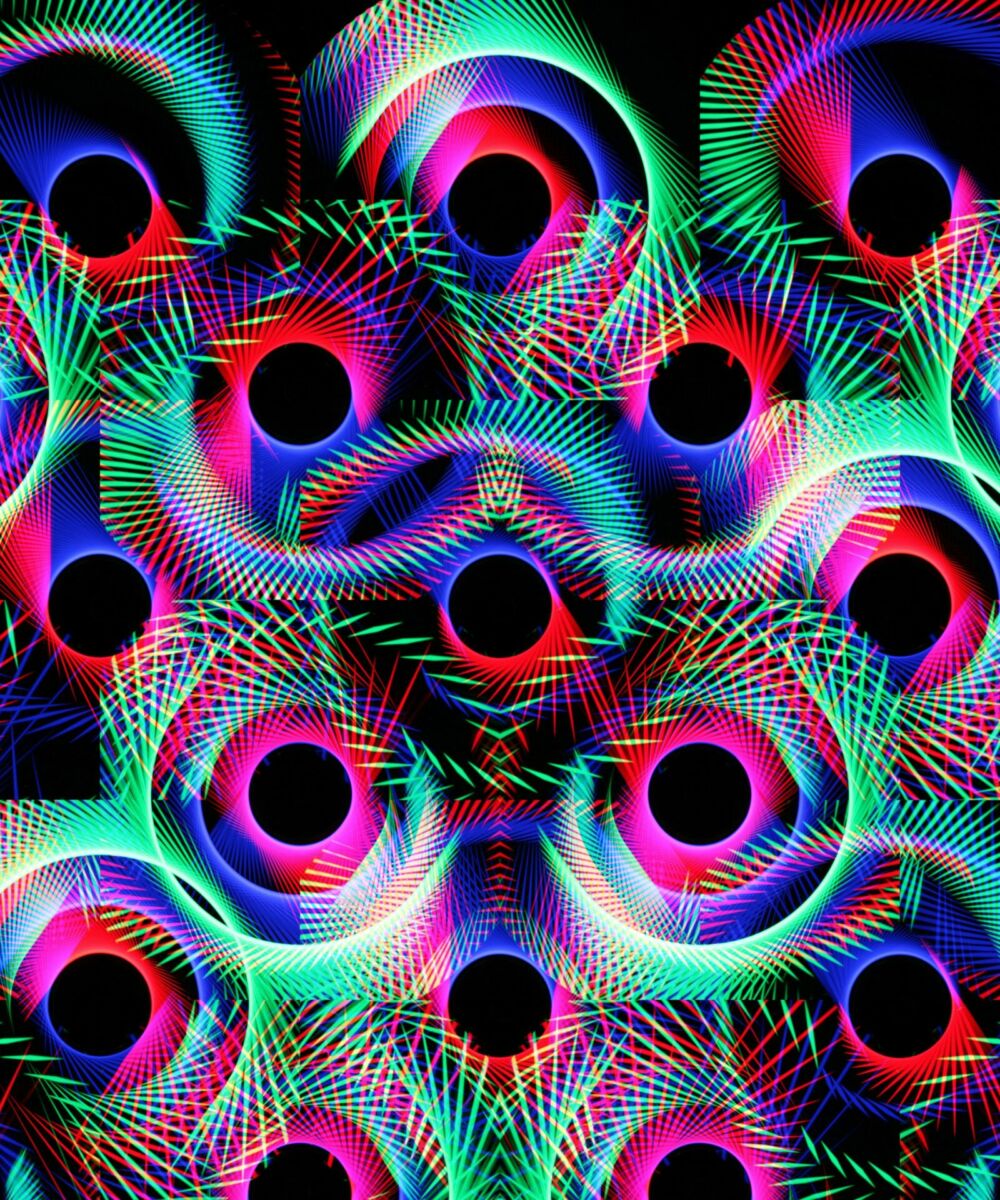

However, she won international fame for having built a virtual “Gotham city”, called RMB City (2006-2011) on “Second Life”, the famous virtual world community launched in 2003, where it is possible to buy property, get married, and set up businesses through a digital alias. Cao Fei operated in “Second Life” through the avatar China Tracey. RMB City is an island metropolis composed of a heap of souvenirs and stock images that she describes as a “condensed incarnation of contemporary Chinese cities”, complete with chimney stacks, statues of Mao, shipping containers and shopping malls. She has documented the city using a vast range of mediums, from videos and virtual guides to a theatrical production on “Second Life”.

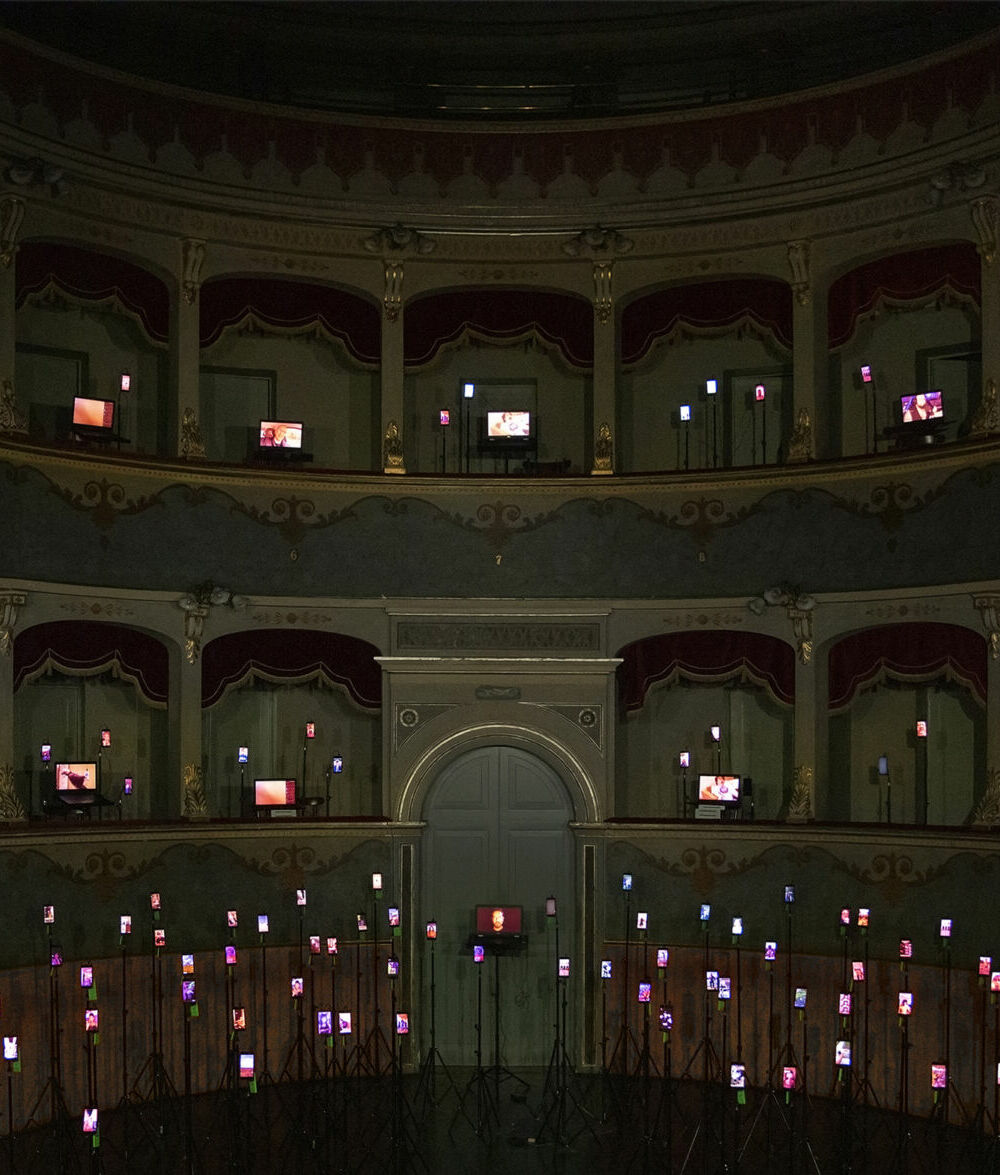

In recent years she has concentrated on analysing the changes in the Hongxia district, on the outskirts of Beijing, with her HX project : it has demanded four years of meticulous research carried out by the artist and her team. HX embraces a perspective seen through a magnifying glass to reveal the rich and complex history of a district undergoing rapid transformation. In this way, the artist has been able to (re)describe and (re)imagine the past, present and future of a community experiencing constant change, as it moves among the currents of our urbanised and globalised society. The focal point of the project is the theatre of Hongxia, built during the period of intense industrial development between the 1940s and 1960s, mainly funded by the Communist allies of the USSR. During this period, the rural district was rapidly transformed from a rural community to a conglomerate of industrial infrastructures, essential in the history of electronic development. This was where the very first Chinese computer was invented.

Cao Fei has scrutinised the social consequences linked with rapid technological progress with a critical eye, able to place the viewer before a silent and invisible dystopic vision of the present

In the HX project, Cao Fei assumes the role of a digital archaeologist and proposes alternative versions of the history of Hongxia, similar to her film, Nova (2019). Cao Fei’s fascination for Chinese-Soviet relationships and the remaining Russian legacy left in China, was in fact stimulated by the history of the theatre of Hongxia and filmed in her full length film, Nova, with the heart-rending love story between two Chinese and Russian scientists, protagonists in a secret research program carried out by an imaginary computer engineering company. The objective is to transform human beings into a means of digital interception, but during the experiment, the Chinese scientist’s own son is trapped inside cyberspace. Now reduced to being a digital soul blocked in a solitary universe, the boy wanders without any way of escape, paying the price of technological research at his own cost. Again, based on the Hongxia Theatre, Cao Fei created a virtual reality experience with Eternal Wave (2020), where the artist herself invited spectators to explore her own art studio space in the old theatre.

Solitude and alienation are the other side of the coin in the insatiable race towards technological and digital progress. Her work is a dystopic crescendo, where multimedia works reveal the more “inhuman” side of our existence, a characteristic that could eventually lead us to a day when we all become zombies, as shown in the film, Haze and Fog in 2014. Cao Fei describes “her” China and the dreariness of the industrial outskirts of Beijing, where life between apartment walls becomes a sequence of senseless actions, driven by the boredom and apathy of the protagonists.

The artist focuses on people belonging to the Chinese middle classes, described as figures who wander through “foggy” modernity, between their domestic cells inhabited by baby-sitters, estate agents, domestic cleaners, prostitutes and delivery men. What she is probably trying to convey, is the fact that all our minds have been clouded by the miracles of modernisation, but we sense a constant need to feel alive and to see the confusing path of our existence more clearly.

Camilla Fatticcioni

China scholar and photographer. After graduating in Chinese language from Ca’ Foscari University in Venice, Camilla lived in China from 2016 to 2020. In 2017 she began a master’s degree in Art History at the China Academy of Art in Hangzhou, taking an interest in archaeology and graduating in 2021 with a thesis on Buddhist iconography from the Mogao Caves in Dunhuang. Combining her passion for art and photography with the study of contemporary Chinese society, Camilla collaborates with a number of magazines and edits the Chinoiserie column for China Files.