A Secret Third Fire

or How to Embrace Our Contradictions in Representing Disasters Online

by Viola Giacalone

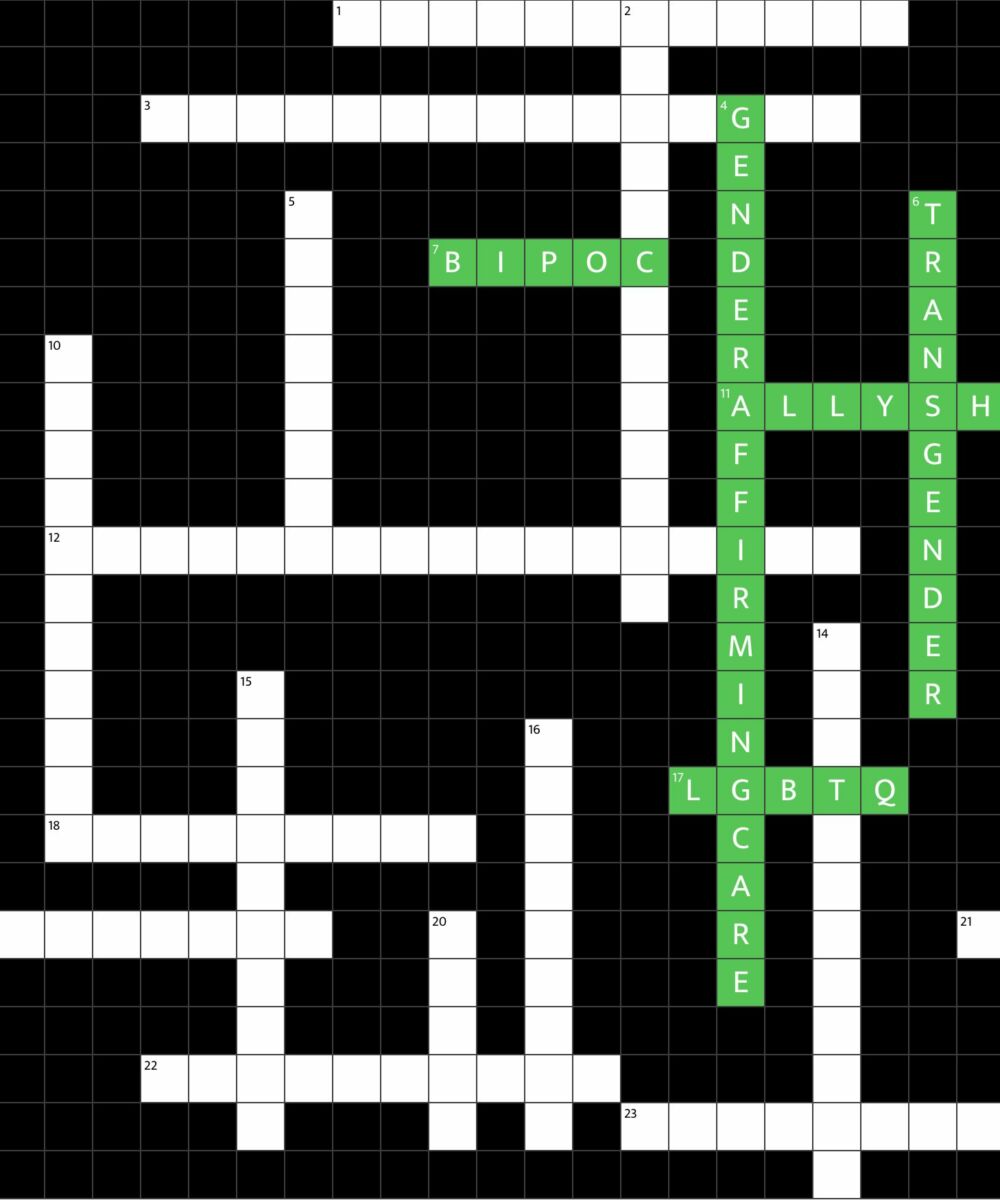

Between real flames, real wars, and digital filters, we cannot agree on the right or wrong way to post about pain online—forgetting that social media are structurally ambiguous platforms, just like us.

Many of us have often wondered whether it makes sense to post Instagram stories about political and social issues, fearing that the medium might trivialise our thoughts and turn them into a narrative about ourselves—especially if the next story shows us smiling at a restaurant with friends. The same eternal dilemma arises when people share personal struggles online, often leading observers to think: “If they’re feeling so bad, why do they have time to film themselves crying?”

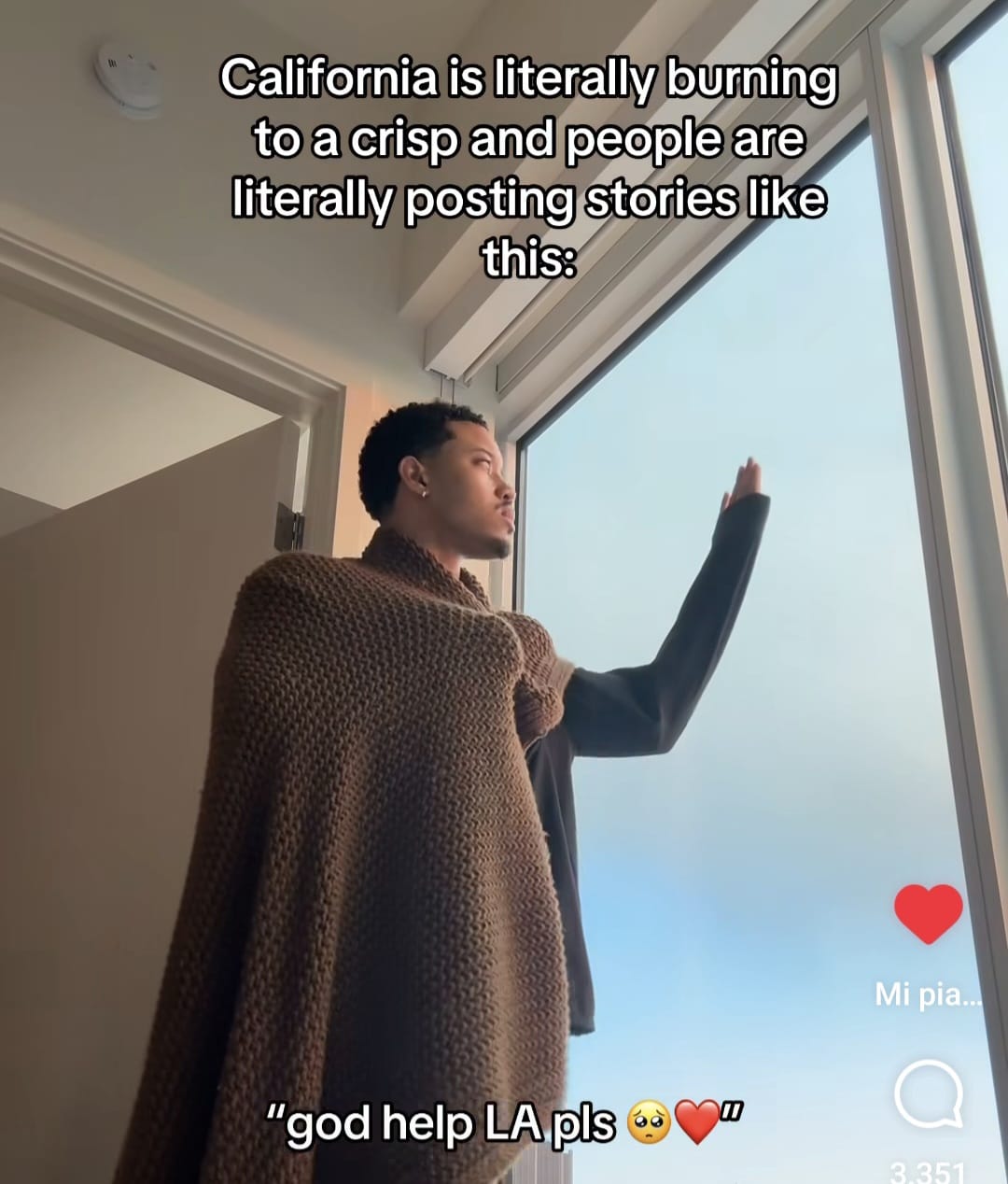

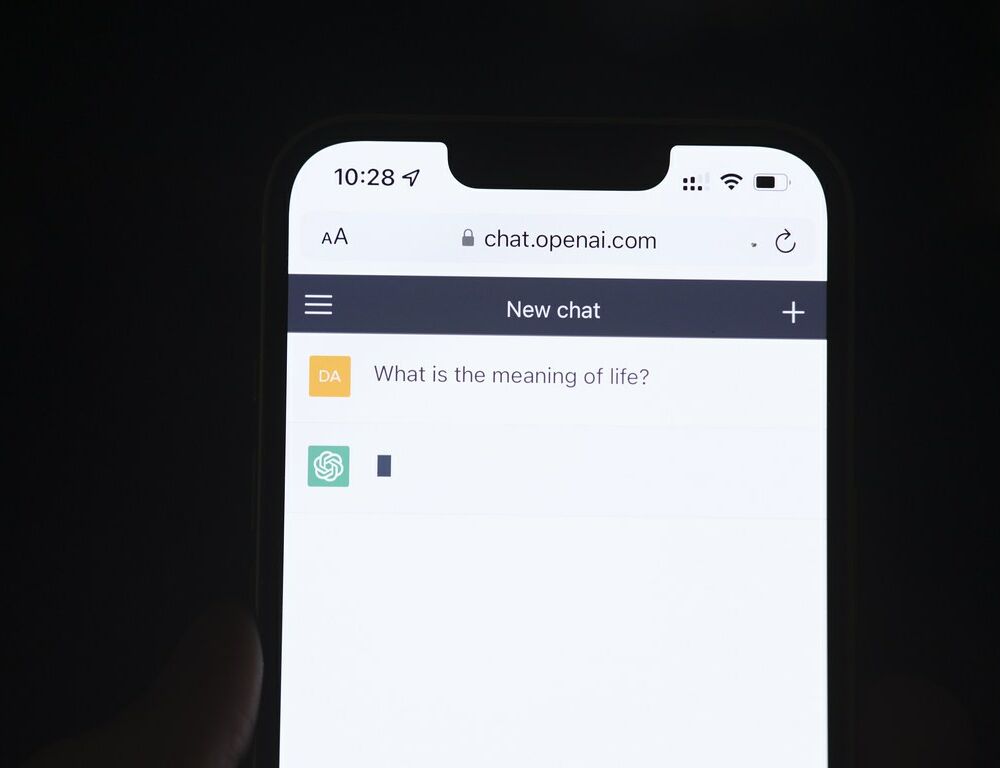

Take, for example, the wildfires that swept through Los Angeles in January, destroying thousands of homes. With their purple skies and burning palm trees, they became the subject of countless posts and stories, often accompanied by filters and music. This triggered a reaction from those who saw the content—many of whom were sceptical or outraged.

The outrage, in this case, stemmed from the assumption that anyone living in Los Angeles must be wealthy and therefore privileged even in catastrophe. But beyond the affluent internet celebrities and VIPs we follow, LA is largely made up of middle- and lower-income residents, many of whom posted content about the fires just like everyone else. The same phenomenon is occurring right now on the east coast of Australia, where Cyclone Alfred is causing severe damage to nature and infrastructure. Viral videos have emerged of locals playing in the mud, in the waves, or even joking about the hurricane.

These recent events have reignited a debate: where is the line between creating personal visual records of a disaster and the unsettling, growing aestheticisation of tragedy? Have we lost our grip on reality?

More than half of the global population uses social networks; they have become such an integral part of our lives that what happens there can influence politics and the economy. For some, social media is simply a way to stay in touch with friends and family; for an increasing number of people, it is a source of income. Perhaps it is time to accept that the only way to post without ambiguity is to stop posting altogether.

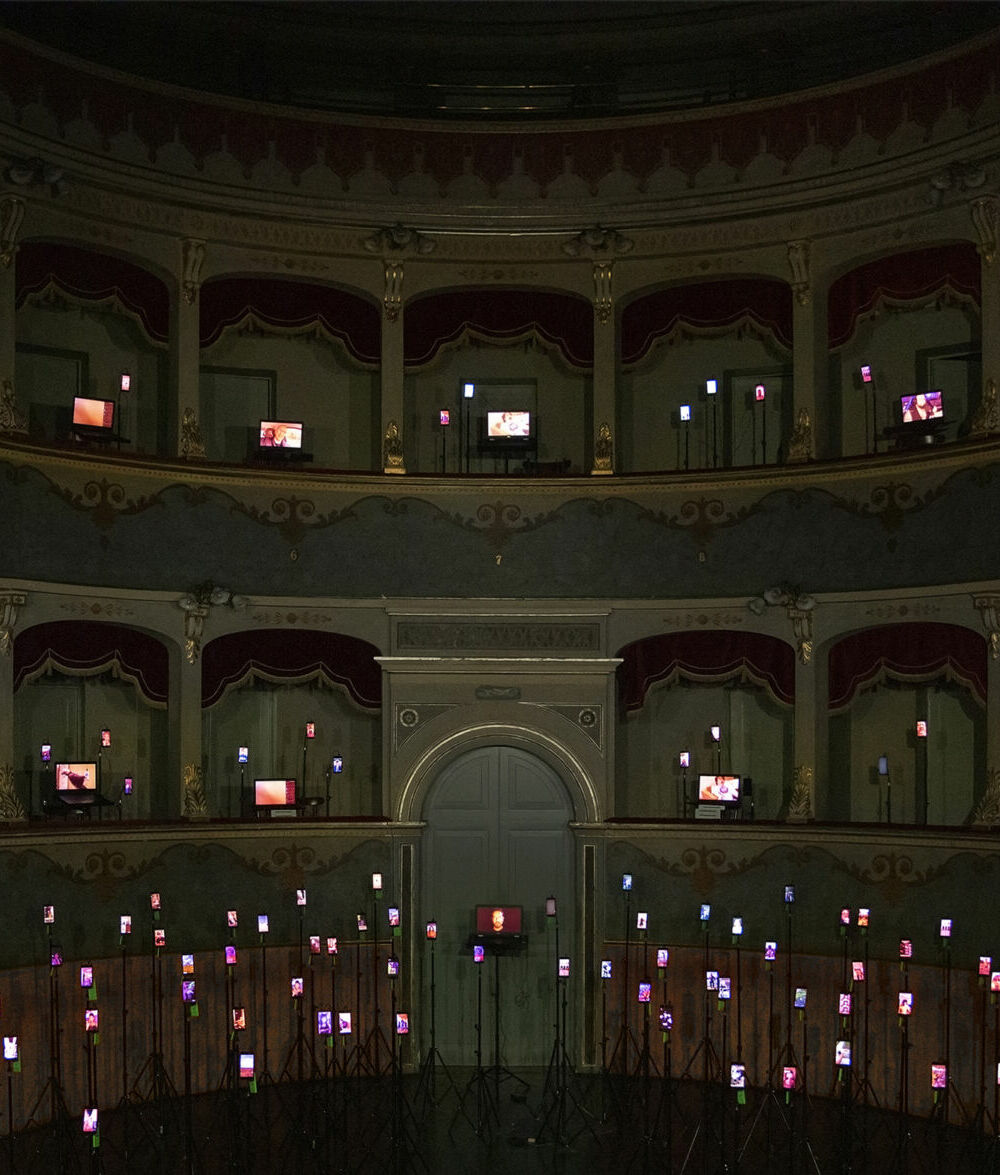

In her book Affective Publics, Zizi Papacharissi explains how emotions circulating on social media create ambiguous human connections. When someone posts a video of flames threatening their home, that content can be both a cry for help and a personal narrative

The issue is not in the act of sharing itself but in the lens through which we view it: we are quick to interpret every post as narcissism, forgetting that the urge to document is also a form of resistance to chaos—and for some, much more than that. Consider, for example, how residents of Gaza have used social media in recent months to draw attention to the horrors they are enduring under siege.

Undoubtedly, FOMO also plays a role in some cases: witnessing an extraordinary event without documenting it can feel like a missed opportunity to participate in the global narrative. This tells us a lot about our desperate need to feel part of a community. Even when we do not experience tragic events firsthand, our instinct is to share the information online. It is not a real solution to the problem, but it makes us feel less powerless in the constant stream of bad news we are exposed to.

The sense of disconnection we feel as observers of such content may be linked to what Jean Baudrillard calls hyperreality

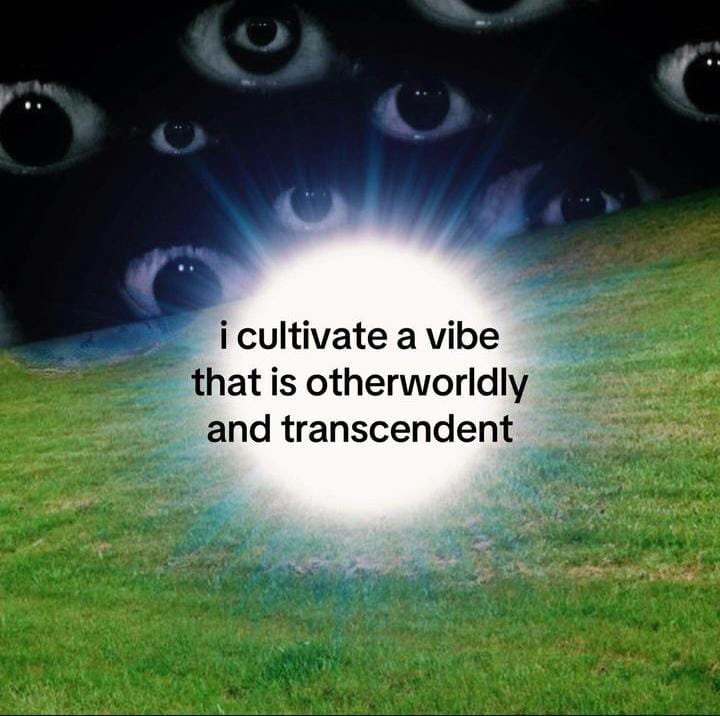

The sense of disconnection we feel as observers of such content may be linked to what Jean Baudrillard calls hyperreality: on social media, images lose their original meaning. A photo of a fire becomes a visual artwork—captivating but numbing. As Susan Sontag reminds us in Regarding the Pain of Others, images can bring us closer to suffering, but they can also distance us from it, turning pain into entertainment—a process of detachment that also enables much of online meme culture (we often find ourselves laughing at or appreciating memes derived from images of suffering).

At the heart of every post lies a paradox: the desire to humanise an experience through a medium that inevitably turns it into spectacle. The problem is that we tend to treat social media like a courtroom—judging both ourselves and others—forgetting that these platforms are carefully designed to make us feel like we are constantly on stage. Yet, on that stage, all we find is a distorted mirror of our own contradictions. It is up to us to keep questioning how we engage with it and to do so in the way we find most meaningful or constructive. Every online action is complex, driven by a mixture of emotions and needs, and no matter how hard we try to categorise it, it will always remain a “third secret thing”—an enigma of our human existence in the digital age.

Viola Giacalone

Viola Giacalone, or Viola Valéry, born in Florence in 1996, is a Florentine journalist, writer and memer. She graduated in comparative literature at the Sorbonne Nouvelle in Paris, with a master’s thesis on new creative writing on the web. She continued her studies in cultural journalism at the City College of New York and at the Accademia Treccani in Rome. She currently collaborates with various publishing, cultural and radio organisations (Controradio Florence, RadioRaheem Milan).