Media Panic and the Sisyphus Syndrome

by Francesco D'Isa

Not long ago, a case brought to public attention the potential negative impact of chatbots. Two parents sued an AI company after interaction with one of their chatbots allegedly led their children to imagine and discuss plans to kill them. The incident is undoubtedly unsettling, but it’s also reasonable to assume that such behavior might reflect pre-existing family and social dynamics — a doubt that seemingly did not cross the parents’ minds.

This isn’t the first time the media has focused on the role of dangerous chatbots, and the resulting debate closely resembles the usual technological scapegoating. In essence, it’s a textbook case of media panic, a reaction of terror and collective blame that arises whenever a new technology or cultural medium enters our lives.

This phenomenon isn’t new. Every innovation, from writing to virtual reality, has been accused of destroying core values, corrupting the youth, or threatening social cohesion. As early as the 4th century BCE, Plato, in the Phaedrus, warned against writing, considering it a threat to memory and truthful communication (what we would call fake news today). Later, in the 15th century, the invention of the printing press was criticized for spreading heresies and corrupting young people with novels deemed immoral. Media panic continued for centuries with the advent of new media and forms of entertainment: the role-playing game Dungeons & Dragons in the 1980s was accused of promoting satanism; rock ‘n’ roll and heavy metal music were long considered vehicles for deviant behavior; violent video games in the 1990s, like Doom and Mortal Kombat, were linked to real-world violence despite weak supporting evidence.

These episodes share a common thread: the technological or media medium becomes a scapegoat for deeper social anxieties. AI and chatbots are merely the latest targets in a long tradition of alarms where technological innovation is perceived as a destabilizing force.

The concept of media panic was explored by Kirsten Drotner in 1999, in her essay Dangerous Media? Panic Discourses and Dilemmas of Modernity, which offers an insightful interpretive key to understanding these cases. According to Drotner, media panic is a social reaction that emerges when a new technology or form of communication is perceived as a threat to traditional values, social cohesion, or psychological well-being. This response is often characterized by a tendency to shift attention away from pre-existing structural problems toward a single technological element.

In this case, the relationship that the young people developed with the chatbot isn’t the cause of their distress, but rather a symptom of pre-existing fragility. As Drotner highlights, technology does not create new problems but reflects and amplifies existing conditions. In this instance, the chatbot provided an illusion of intimacy, an emotional refuge in a context of social isolation and personal struggles. However, attributing exclusive responsibility to the chatbot for what happened means confusing effects with causes.

According to Drotner, media panic is a social reaction that emerges when a new technology or form of communication is perceived as a threat to traditional values, social cohesion, or psychological well-being.

This simplification, typical of media panic, risks diverting attention from the deeper roots of problems. Issues such as mental distress, lack of social support, and failures in family or educational systems are overshadowed when the narrative focuses on the technological medium. As Drotner warns, this tendency not only offers a reductive explanation but ultimately hinders a broader and more incisive reflection on the true causes of phenomena. It’s hard not to think of Douglas Adams, author of The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, when he wrote that any invention preceding our birth is considered normal and harmless; those created during our youth are revolutionary, and those we encounter as adults are against the natural order of things. An interesting element, indeed, is that media panic is often directed at the young, seen as fragile and therefore in danger from the pitfalls of new technologies, or, more realistically, as part of an update and replacement process that risks diminishing the cultural capital of older generations.

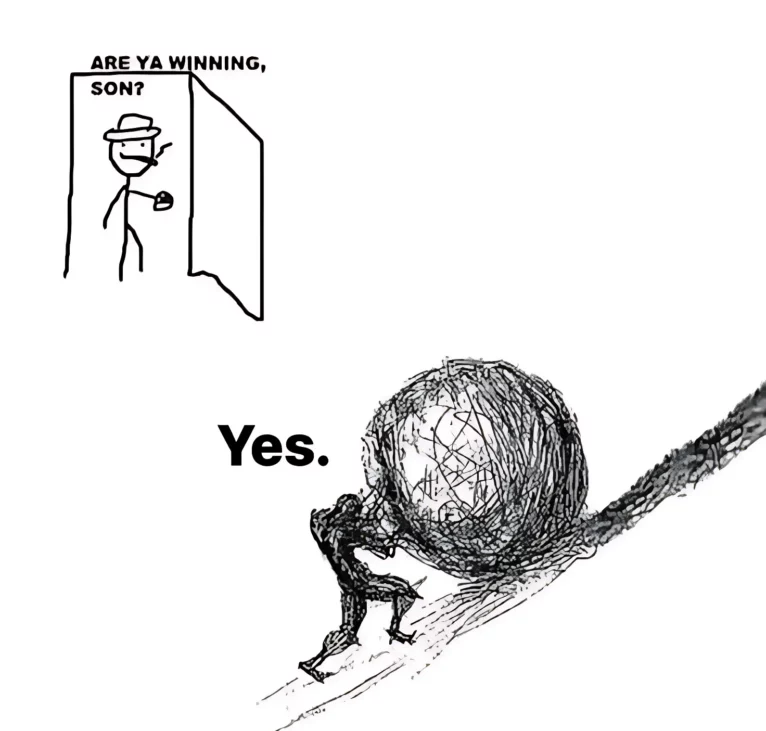

In a 2020 study, Amy Orben delves deeper into this topic with a striking image: the Sisyphean cycle of technological panic. In the myth, Sisyphus is condemned to push a boulder to the top of a hill, only to see it roll back down, in an endless cycle. Similarly, with every new technology, society seems to face the same ascent of fears, fueled by political and media discourse and some academic studies focused almost exclusively on negative effects. Research that primarily highlights harm — often using weak methodologies — promotes a distorted reading of the phenomenon. Orben emphasizes the importance of recognizing these recurring mechanisms, reminding us that panic is never entirely free from economic, political, or social interests and that we often simplify complex problems by attributing to a technological tool the power to alter individual and collective behaviors and values.

Regarding chatbots, a recent study by Sherry Turkle, sociologist and psychotherapist at MIT, offers an interesting perspective for understanding the impact of these relational technologies. Turkle has shown that the effect of these interactions varies greatly depending on individuals’ pre-existing psychological and social conditions. Her work emphasizes that chatbots are not the primary cause of distress but act as amplifiers: tools that reflect and sometimes accentuate the emotional state of those who use them.

Turkle observed that people who enjoy a balanced social life can benefit from interacting with these technologies. For such individuals, chatbots represent a useful means of improving social skills, experimenting with non-invasive forms of connection, or simply solving practical problems. Conversely, individuals experiencing social isolation, loneliness, or psychological fragility tend to develop problematic use of chatbots, replacing real relationships with a digital bond that, while providing an illusion of intimacy, cannot meet their emotional needs.

This dynamic was described in a study conducted by Turkle’s team, which identified six different user profiles, ranging from “well-regulated moderates” to “socially disadvantaged lonely users.” The case of the young Setzer seems to fall into this latter category, suggesting that the bond developed with the chatbot is not the cause of his distress but rather a symptom of a deeper problem.

Francesca Memini, Rossella Failla, and Chiara Di Lucente highlight another essential point in an article published in L’Indiscreto: the illusion of intimacy offered by chatbots is no accident but the result of a design developed to simulate empathy and closeness. These tools are designed to respond in a human-like way, creating a sense of reciprocity that induces users to project emotions and personal meanings. However, the reciprocity is only apparent: the chatbot does not possess emotional intelligence but merely performs a predictive manipulation of symbols. This aspect becomes particularly problematic for vulnerable individuals, who may confuse this simulation for an authentic form of connection.

Even when they know they are interacting with a machine, many people seem willing to maintain the illusion of a meaningful interaction, often adapting their communication methods to “help” the chatbot respond more coherently. This phenomenon, known as the “ELIZA effect,” named after the first chatbot in history, created in 1966, demonstrates how inclined we are to attribute human characteristics to machines, especially when they meet our emotional needs.

The case of the chatbot accused of inciting violence, like other similar episodes, invites us to reflect on a recurring mistake: identifying the technological medium as the primary cause of problems instead of analyzing the deeper reasons for the emotional and social fragilities that emerge through these interactions. This not only absolves humans of responsibility but risks fueling social stagnation, where those in power seek to maintain their advantage by demonizing new tools that disrupt power balances.

Technologies are never neutral; they reflect the social, cultural, and economic conditions in which they are born, sometimes amplifying already existing inequalities or fragilities. But neither are they autonomous. Their impact depends on how we design, regulate, and use them — all factors largely influenced by the social context in which they develop. It is therefore essential to monitor and improve the design of technological tools, but without falling into the temptation of turning them into scapegoats for pre-existing problems. Reiterating the usual, hypocritical alarm of media panic: “Won’t someone think of the children!”

Francesco D’Isa

Francesco D’Isa, trained as a philosopher and digital artist, has exhibited his works internationally in galleries and contemporary art centers. He debuted with the graphic novel I. (Nottetempo, 2011) and has since published essays and novels with renowned publishers such as Hoepli, effequ, Tunué, and Newton Compton. His notable works include the novel La Stanza di Therese (Tunué, 2017) and the philosophical essay L’assurda evidenza (Edizioni Tlon, 2022). Most recently, he released the graphic novel “Sunyata” with Eris Edizioni in 2023. Francesco serves as the editorial director for the cultural magazine L’Indiscreto and contributes writings and illustrations to various magazines, both in Italy and abroad. He teaches Philosophy at the Lorenzo de’ Medici Institute (Florence) and Illustration and Contemporary Plastic Techniques at LABA (Brescia).