From Bauhaus to AI: Moholy-Nagy’s vision reinterpreted by David Szauder

by Alessandro Mancini

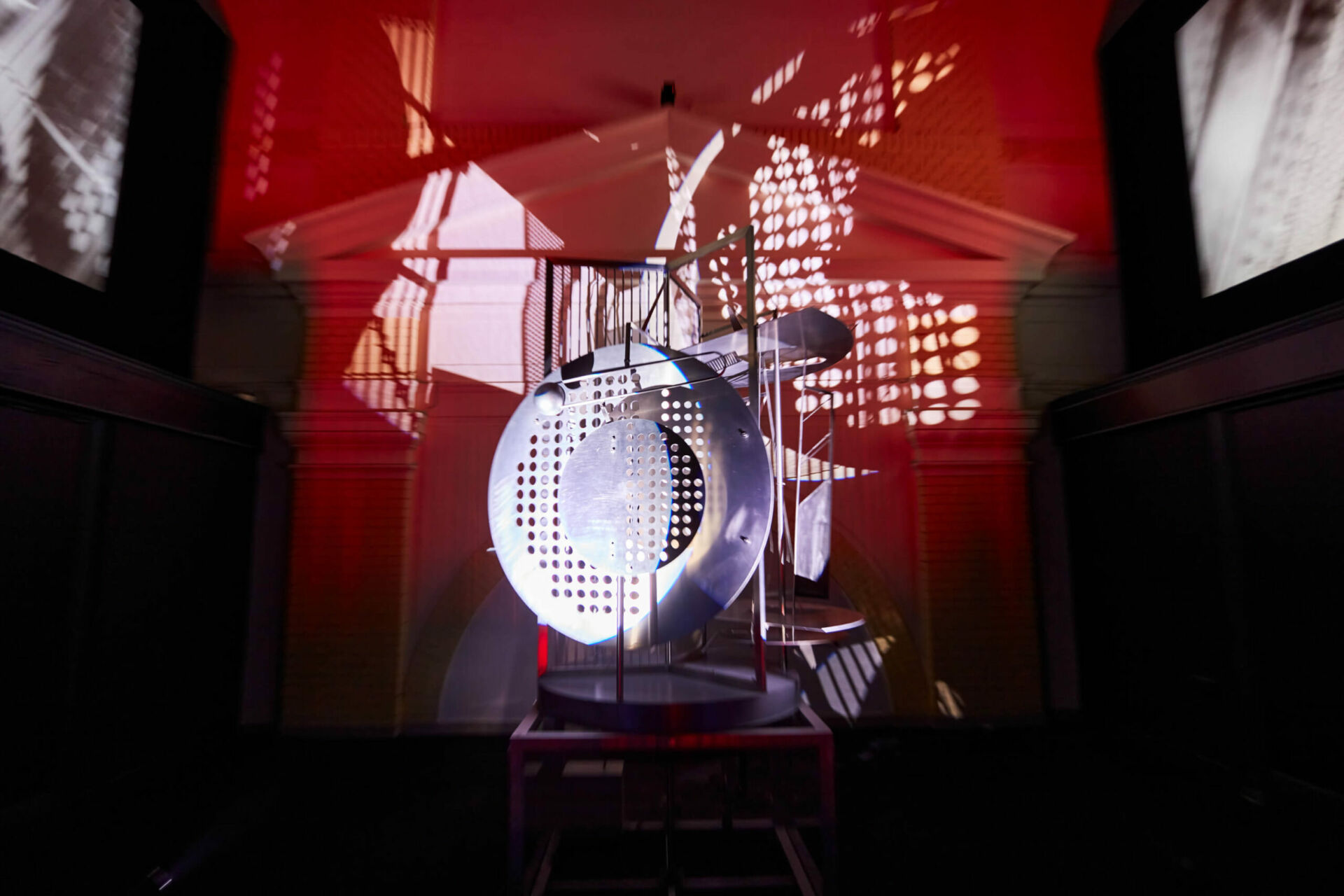

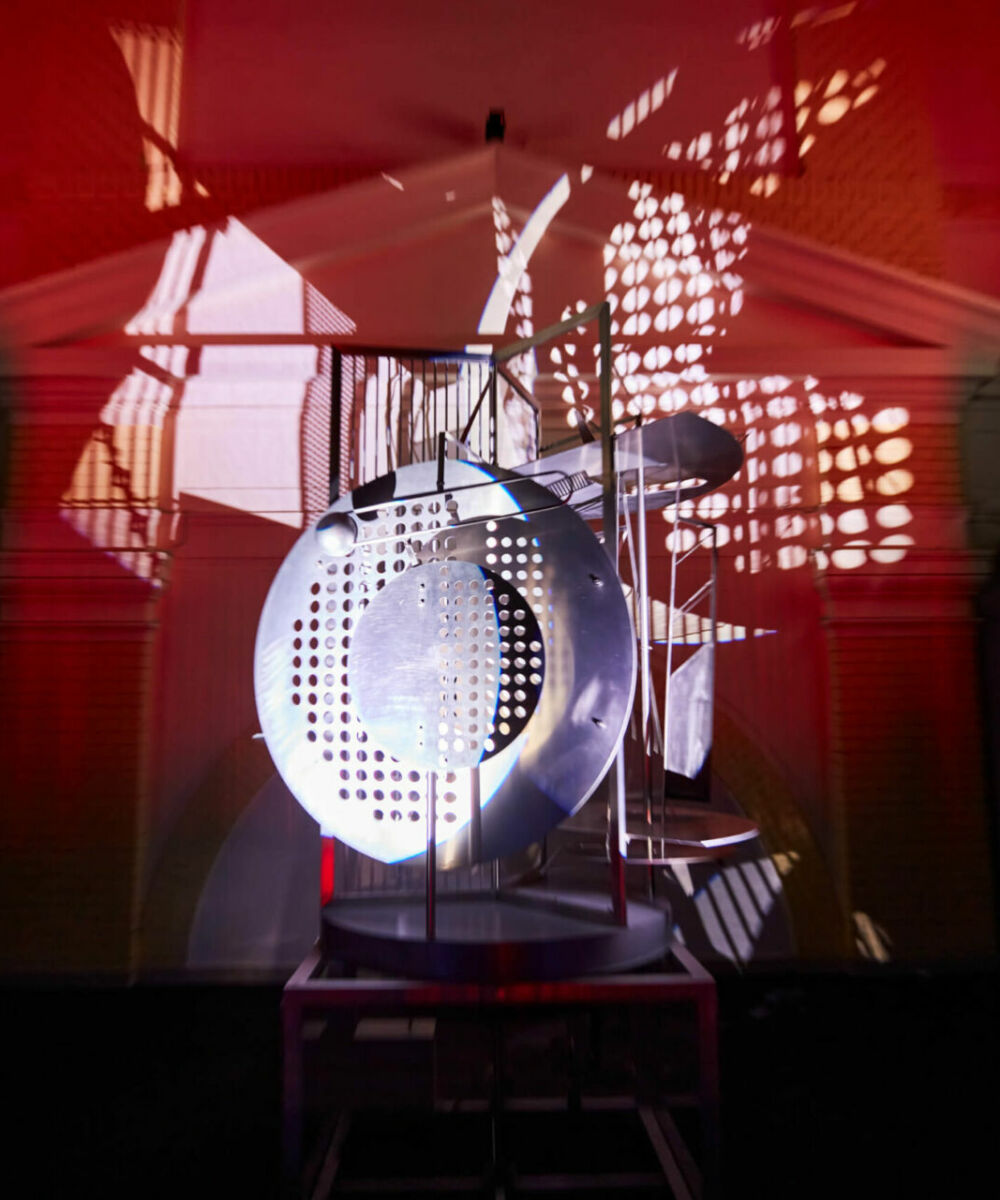

Opening the eighth edition of Fotonica, Rome’s audio, visual and digital art festival, is an installation by Hungarian artist David Szauder, inspired by none other than an iconic work by painter, photographer, designer and constructivist theorist László Moholy-Nagy, Light Prop for an Electric Stage.

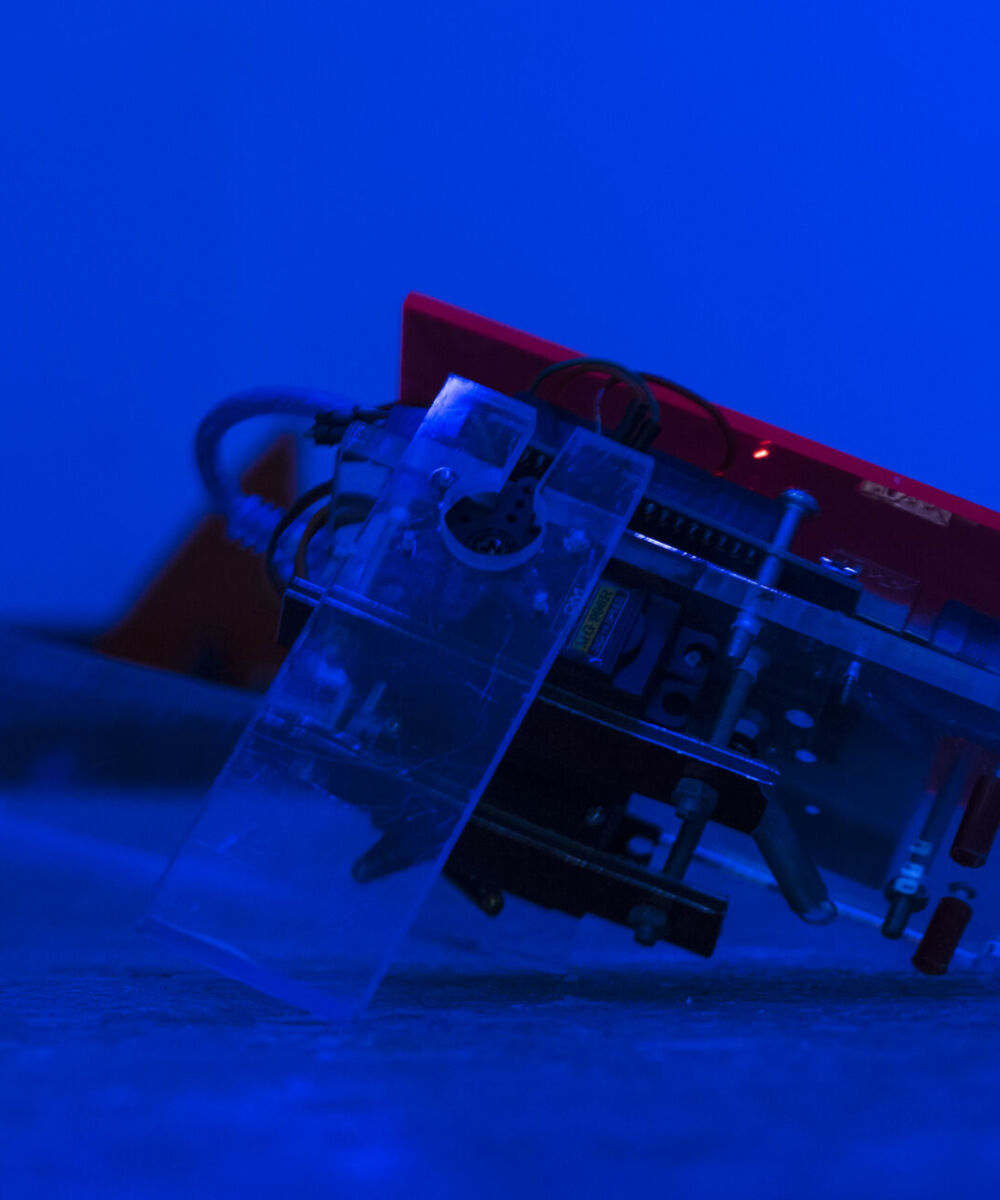

The work, conceived by László Moholy-Nagy and designed by architect István Sebők, was initially intended to be an ‘experimental light-painting device’ with the potential to use information from different artistic fields to make it work. Starting from the work’s prototype (the original is exhibited in the Harvard Museum collection), Szauder created an interactive performance that, taking into account Moholy-Nagy’s aesthetic-educational programme, is enriched with an auditory experience that responds to the environment of light and shadow created by the sculpture’s movement.

It will be hosted, until Saturday 21 December 2024, in the courtyard of the elegant Palazzo Falconieri, seat of the Hungarian Academy in Rome.

“As a child, I was very fond of old photographs,” Szauder recalls. “I enjoyed trying to figure out who the people in the pictures might have been and where the photo was taken. I think it was a genuine curiosity that, while it hasn’t disappeared over the years, has transformed into a more conceptual interest. Now, this curiosity is no longer just about places, people, and situations, but also about the meaning of the image itself.”

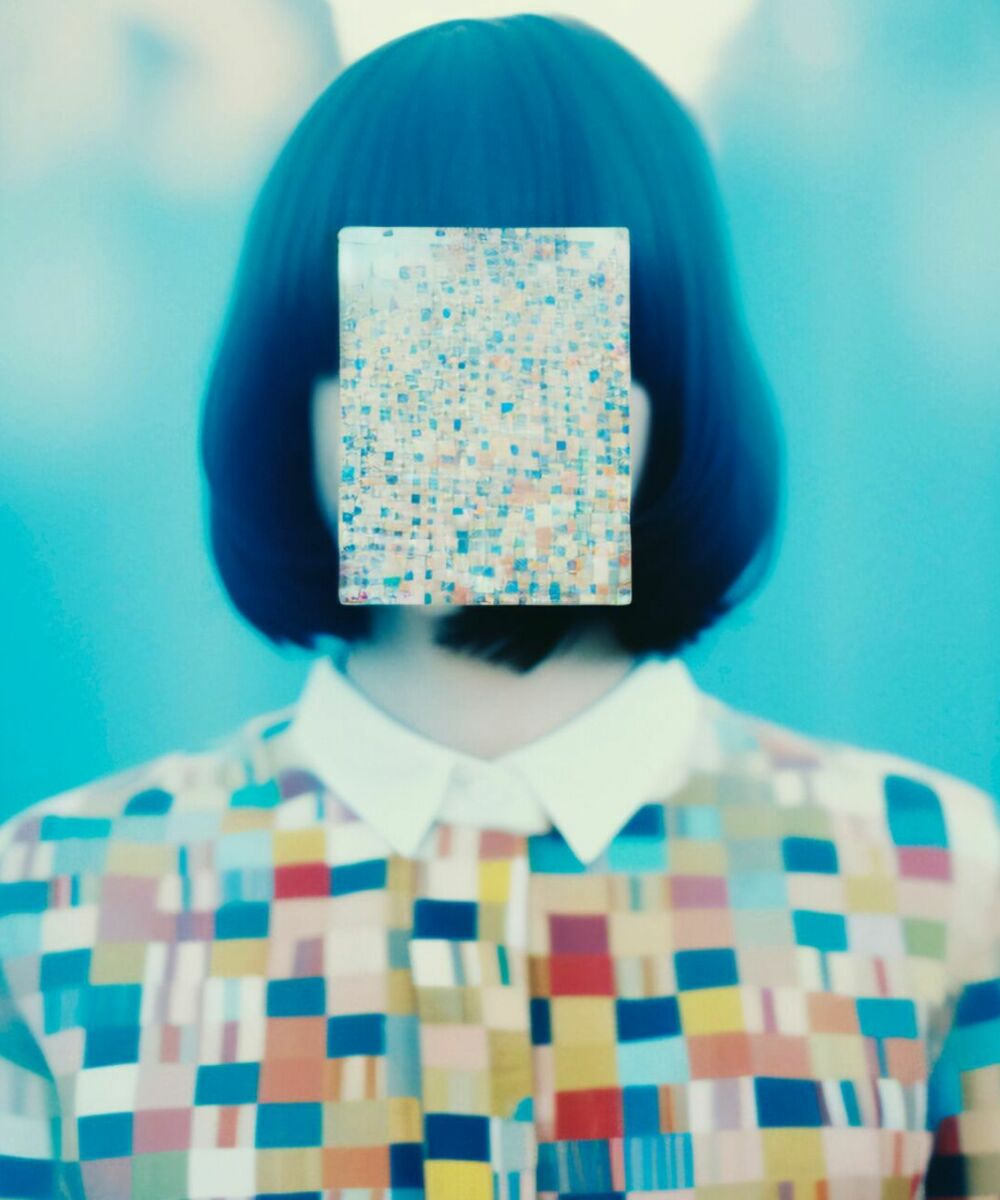

Today, the Hungarian artist’s curiosity revolves particularly around the genesis of an image: “It’s not just about what we see in a photograph but also how we remember it afterward, often with details that differ from those we originally observed. From that moment on, the image takes on a parallel life and identity in our memory. This explains the phenomenon where, when recalling an image, it adopts different characteristics than what we initially saw. To make this idea even more complex,” he continues, “as we visualize an increasing number of photos, images, and real-life scenes, we start blending these images in our minds. We can easily forget the sources of the original images and use our memory to recreate them in a personal way. However, in this process of recreation, we inevitably rely on images and photographs already stored in our memory, a sort of ‘trained’ collection.”

Szauder thus draws a parallel between the method of generating images in the human brain and that used by AI. “That’s how I came into contact with artificial intelligence and found a way to celebrate the birth of the image,” he says. “It feels like a love letter, doesn’t it?”

“My father is a professor of cardiology,” he recalls. “I remember sitting on the floor in his room when I was 8 or 9 years old, spending hours leafing through his human anatomy atlas. They were enormous blue books with a distinctive smell. I’m certain those images are somehow stored in my memory. I was fascinated by the organic structures of veins and arteries, by how they crisscrossed the human body, forming intricate connections. The human body appeared to me as a perfectly designed visual system.”

This, however, was only the initial approach. Later came fears and anxieties: “I also developed a fear of severe illnesses, especially after a friend my age became gravely ill. It was an experience that left a profound mark on me. I started noticing the ironic side of the human body: it’s something that stays with us for our entire lives, but it’s mostly invisible. If we could see it, well, that would be an entirely different story.”

That’s when the artistic intuition struck: “How could I work on this contradiction visually? That’s where the concepts of ‘inside-out’ and the sweater were born. The sweater—soft, comforting, and warm—contrasts with the hidden complexity of the human body.”

Artificial intelligence proved to be a valuable ally for “creating visual simulations, as long as you know how to work with it,” the artist emphasizes. “It does require a learning curve, but that’s another story. In any case, using anatomy books, samples, and photographs as sources, the prototypes eventually came to life.”

"Non si tratta solo di ciò che vediamo in una foto, ma anche di come la ricordiamo in seguito, spesso con dettagli diversi da quelli che abbiamo osservato in origine. Da quel momento in poi, l'immagine assume una vita e un'identità parallele nella nostra memoria. ”

In the installation Modulator V3 (Paraphrase of László Moholy-Nagy’s Light Prop for an Electric Stage), scheduled to appear at the Fotonica 2024 Festival, Szauder reinterprets an iconic work of Hungarian modernism, originally created in 1930.

“The image of the original installation is part of my childhood’s visual experience and memory,” the artist explains. “I used to look at it often, but I couldn’t imagine what it did, how it worked, or what it was for. To understand it, I had to redesign the entire structure and rebuild it. This is the longest project of my creative career because I’m still working on it, even involving artificial intelligence to optimize some parts.”

László Moholy-Nagy was a leading figure of the Bauhaus movement and a key influence on 20th-century art, thanks to his ability to foresee the dialogue between art, technology, and industry. His work has shaped the trajectory of many later artists, including Szauder himself.

“I’ve learned a lot from the Bauhaus masters,” the Hungarian artist recounts, “not only from Moholy-Nagy but also from Oskar Schlemmer, who is another fundamental role model for me. Regarding Moholy-Nagy, his approach to integrating education and creation was particularly significant. As an artist teaching at a university, I also face countless questions, and in my case, the inclusion of technology, particularly artificial intelligence, makes these questions even more complex. I’m currently teaching at MOME (Moholy-Nagy University of Art and Design) in Budapest, and Moholy-Nagy’s way of thinking has been immensely helpful in turning this process into a success.”

In a context of increasing integration between art and AI, Szauder has, in recent years, embraced experimentation and the exploration of new horizons, made accessible through the use of emerging technologies. “The most important question I’ve asked myself over the past three years,” he states, “has been how to integrate artificial intelligence and art into my work. As an experimental artist, I’m constantly exploring new possibilities in digital art. I’ve worked across numerous genres, from robotics to augmented reality. However, my focus is always on how to incorporate these tools into the creative process. The same applies to artificial intelligence, even though,” he emphasizes, “my learning curve has been longer compared to other technologies, especially because there are far fewer established rules in this field. Many people think that a simple prompt is enough to open Pandora’s box and reveal the perfect creation, but that’s not the case. With artificial intelligence, it’s necessary to establish certain workflows and put in considerable effort to authentically convey the artist’s visual language. The real challenge,” he concludes, “will be keeping pace with a technology advancing at an unprecedented speed.”

Alessandro Mancini

A graduate in Publishing and Writing from La Sapienza University in Rome, he is a freelance journalist, content creator and social media manager. Between 2018 and 2020, he was editorial director of the online magazine he founded in 2016, Artwave.it, specialising in contemporary art and culture. He writes and speaks mainly about contemporary art, labour, inequality and social rights.