AI-Generated Avatars Have Taken Over Chinese Livestreaming Platforms

by Camilla Fatticcioni

AI-generated bots are cost-effective, compliant, and never need a break from selling products. But do customers really like them?

Opening apps like Douyin, the Chinese version of TikTok, it’s easy to encounter influencers and live-streamers urging audiences to buy discounted products. The livestream industry is enormous in China: millions of people host live shows on their social channels, selling everything from makeup to luxury real estate. In 2023, the e-commerce livestream market was worth approximately $691 billion, marking a 35% growth compared to 2022. Today, however, the work of live streamers seems at risk due to the rise of Artificial Intelligence (AI).

In recent years, Asia has seen the rise of AI-generated pop stars, models, and even romantic partners. Now, digital avatars are increasingly present on livestream platforms as 24/7, low-cost sellers. Last June, AI avatars hosted live shows for over 5,000 brands during the “618” festival, a Chinese sales event similar to Black Friday. Content generated by these bots amassed over 100 million views and more than 5 million user interactions.

Chinese companies favor this type of “televendor” to cut costs. A digital avatar can be acquired by a company for only a few hundred dollars and doesn’t require a salary. Additionally, companies don’t need to rent a studio or hire sound engineers, makeup artists, or other support staff for live-stream programs involving real people. In 2023, digital avatars generated over $46 billion in revenue in China. By 2025, this figure is expected to reach $90 billion.

AI has opened up many possibilities, but commercial use seems to be the most promising. For several years, many Chinese brands have preferred AI-generated images over real-life models, who have been swiftly replaced by avatars with doe-like eyes and ample features. AI models aren’t exclusive to China, nor is the concept new. Levi’s recently launched a campaign using AI-generated images, and in March, an AI model appeared on the cover of Vogue Singapore.

However, avatars are not yet the highest-quality option. When examined closely, AI-generated models often have unnatural poses and generation errors (AI still struggles to reproduce hands correctly, for instance). Avatars also tend to have issues: they are slow to respond to user questions in chat during sales and follow a scripted, unnatural delivery that might not engage potential buyers.

Now, digital avatars are increasingly present on livestream platforms as 24/7, low-cost sellers.

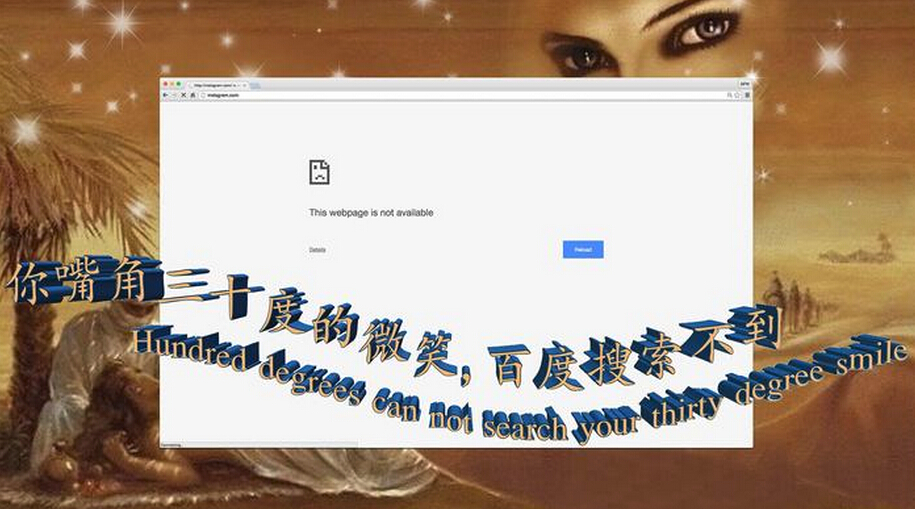

E-commerce insiders remain cautious about using digital avatars. A brand’s reputation often hinges on trust and emotional connection with consumers, which AI bots in their current form may jeopardize. The rise of AI-generated hosts is also causing legal concerns in China. As digital avatars become more realistic, consumers find it increasingly challenging to distinguish between human and AI interactions. This opens opportunities for fraudsters, who use digital avatars to trick buyers into purchasing counterfeit goods. By the time consumers realize they’ve been scammed, the seller has already disappeared.

Last May, Douyin introduced guidelines to regulate the use of virtual avatars, requiring all creators to clearly label AI-generated content. Digital avatar owners must also register on the platform with their real identities, and any AI-generated livestream must be supervised by a human. Digital avatar creators face various potential legal risks. For example, using a real person’s voice could expose the creator to fraud charges. Additionally, since digital avatars engage in commercial activities, creators must obtain consent from anyone whose likeness they wish to replicate.

If used correctly, AI represents a genuine asset that can bring real benefits to businesses. Whether it’s the avatar technology itself, the companies using it, consumers, or related regulations, greater standardization will undoubtedly enable broader application.

Camilla Fatticcioni

China scholar and photographer. After graduating in Chinese language from Ca’ Foscari University in Venice, Camilla lived in China from 2016 to 2020. In 2017, she began a master’s degree in Art History at the China Academy of Art in Hangzhou, taking an interest in archaeology and graduating in 2021 with a thesis on the Buddhist iconography of the Mogao caves in Dunhuang. Combining her passion for art and photography with the study of contemporary Chinese society, Camilla collaborates with several magazines and edits the Chinoiserie column for China Files.