Miao Ying and the Post-Internet Art

by Camilla Fatticcioni

Miao Ying is a Chinese digital artist who is part of the Post-Internet Art movement. Her works reflect the web and its repercussions on society, with a critical, and sometimes ironic view of the censorship of the Chinese “Great Firewall”.

The term Post-Internet Art was introduced in the early years of the millennium to highlight the impact and influence of Internet in the world of art. This neologism describes a type of art that was born “after having experienced online activity”, in other words, art that reflects the web and its repercussions on society. The concept became rapidly widespread, enriched with new meanings, interpretations and uses, sometimes even inaccurate: from simple descriptions of a cultural condition, it soon became a generic label, often applied to a generation of artists influenced by digital culture. Over the years, many Chinese artists have opened up and expanded their reflections on Chinese Internet aesthetics because they are unique and different from those generally recognised in the West, transforming the way to use the web and technology for artistic purposes. In particular, the artist Miao Ying (1985, Shanghai, China) launched a reflection on digital communication in China and on the conditioning imposed by the need to pander to or bypass government censorship. Miao Ying is part of the first generation of contemporary Chinese artists who grew up with Internet, Chinese economic reform, the one-child policy, and the possibility of studying abroad. She is renowned for her projects and writings that place Western technology and ideology in closer proximity to contemporary China.

It is essential to be aware of the distinction between Chinese and global Internet to understand Miao Ying’s art. In China, the Great Firewall is used to block web pages like Facebook, Google, Wikipedia, Youtube and Instagram, which can be accessed in the country only through VPN networks. On the other hand, Chinese social media like Weibo and WeChat often censor certain topics and keywords considered sensitive. In their attempt to by-pass censorship, over time, Chinese netizens have invented a unique web culture and language.

Revisiting young contemporary users’ relationship with technology, Miao Ying’s artistic production is focussed on Internet’s impact on daily life. With a dose of irony, the artist describes her passion and interest for digital aesthetics in relation to the Chinese Great Firewall like a Stockholm syndrome.

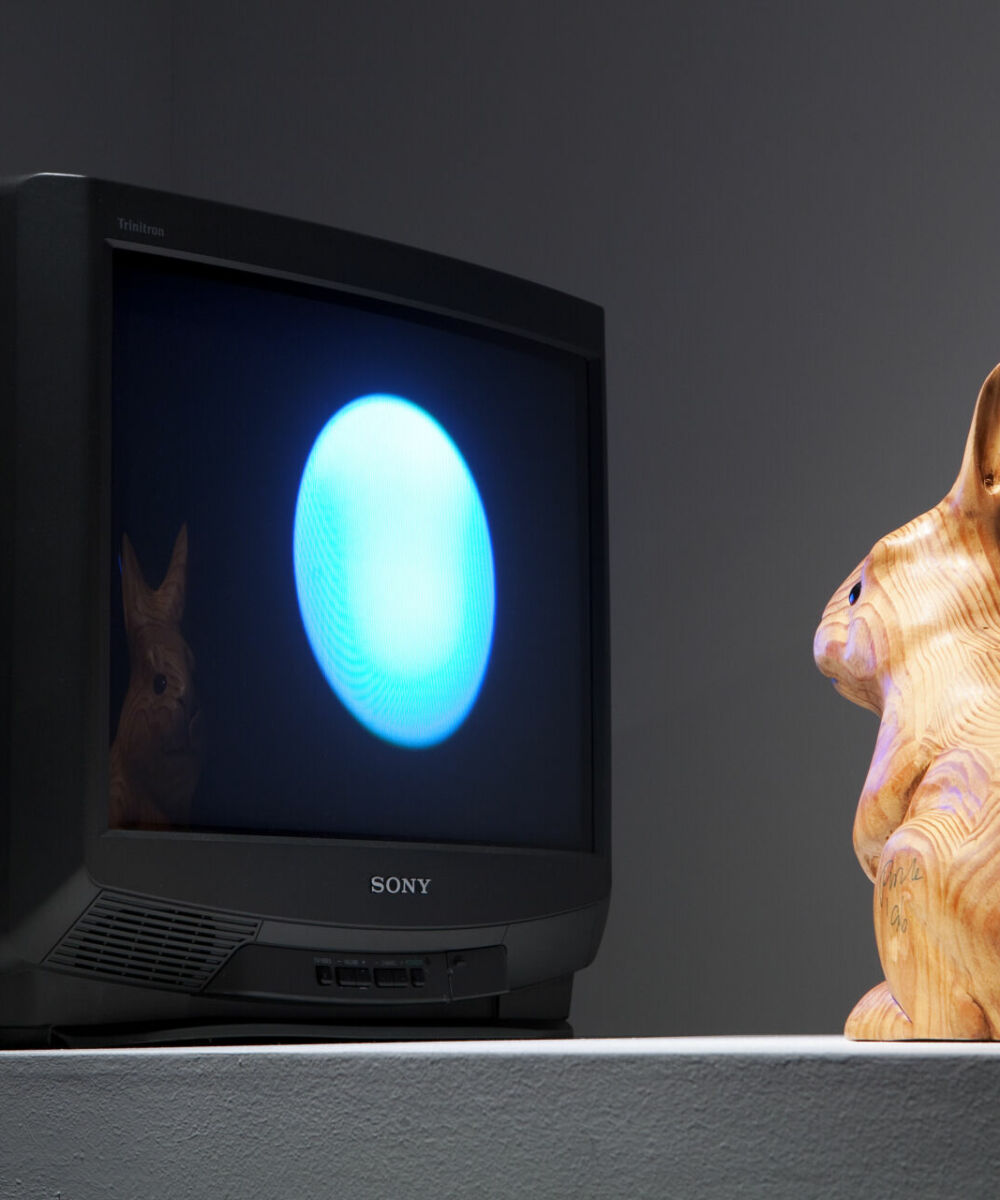

It is precisely this kind of culture that the artist explores in one of her most famous video installations: Holding a Kitchen Knife to Cut Internet Cable, presented at the Venice Biennale in 2015. The work drew its inspiration from a poem that the artist found online. This digital work shows the simulation of certain web pages censored by the Great Firewall, decorated with animated GIFs and lyrical, sentimental phrases to demonstrate the romantic relationship between the artist and the web. The aesthetics of the work are based on a kitsch font in WordArt style, that the artist defines as “animated 3D Taobao style”, in reference to one of the most popular online shopping platforms in China.

la produzione artistica di Miao Ying si concentra sull’impatto di internet nella vita quotidiana. Con ironia, l’artista descrive la sua passione e interesse per l’estetica digitale come una Sindrome di Stoccolma per il Great Firewall cinese.

Once again, in reference to censorship operations on the web, in 2016, Miao Ying created an online exhibition, Chinternet Plus , for the New York New Museum, an extremely innovative concept in pre-Covid years. The project consisted of a “spoof” website inspired by the Internet Plus strategy proposed in 2015 by the Chinese Prime Minister, Li Keqiang, to keep up with new information trends, foreseeing the application of information and digital technologies in traditional industries. Miao Ying described this government initiative as “all style and no substance”, and as a result, Chinternet Plus is a parody of a website full of GIFs and nonsensical language. There is no mention of precise policy or effective plans on Chinternet Plus; basically, the whole idea is a subterfuge made up of falsified images, logos and terms without any significance.

In her most recent project, Love’s Labour’s Lost (2019), Miao Ying films herself as she collects love padlocks attached to a metal railing in Paris. The video is a metaphor for VPN networks used to bypass the Great Firewall. This video is accompanied by a work, Love’s Little Wall, a heart-shaped, wooden cage containing a photo of the Great Wall of China. The combination represents a metaphor of the Great Firewall, the wall that separates Chinese and global Internets, just as the Great Wall protected China from foreign invasion in ancient times. According to Miao Ying, regardless of their shape or form, walls can always be circumvented in one way or another.

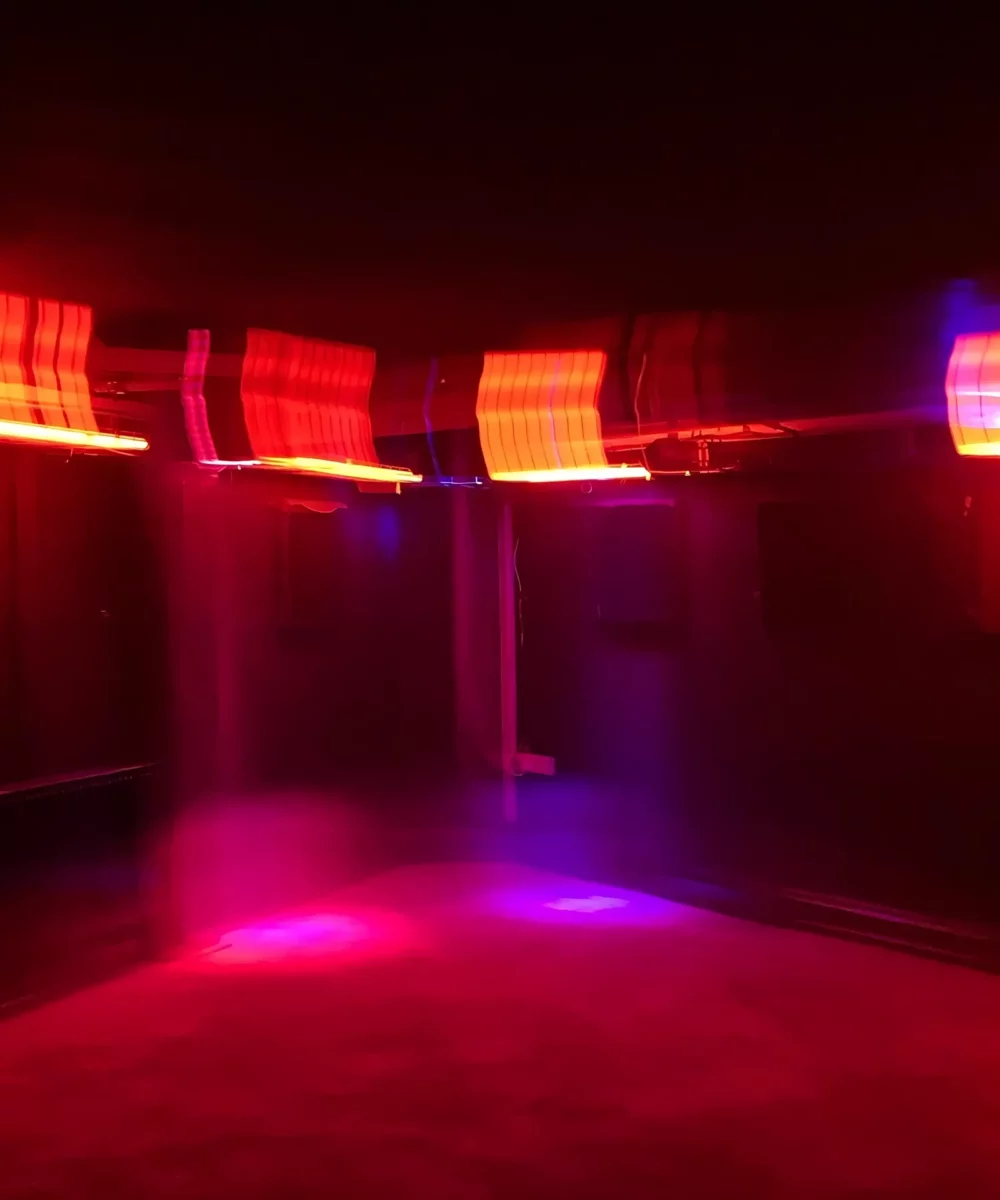

In recent years her work has been focussed on the use of Artificial Intelligence (AI) as in her digital work divided into two chapters: Pilgrimage into Walden XII (2020-2022), which takes place in a magical medieval fantasy land called Walden XII. The work, directed by Miao Ying, was written by GPT3 Artificial Intelligence and simulated on a gaming platform. The name, Walden XII refers to “Walden Two”, a utopian novel written by the behavioural psychologist, B.F. Skinner, about a society in which perfect behaviour is achieved as the result of reinforced positive conditioning of desired behaviour, at the same time satisfying the fundamental needs of the population. In a structure that is similar to that of the church in the Middle Ages, Walden XII is a live simulation and technologically augmented architecture that, by collecting big data or information on its population, rewards or punishes them according to a behaviour points system.

Internet and new digital technologies reflect a society in rapid development, in a constant search for new communication instruments, from animated GIFs to AI, able to write a story for us. Everything becomes a mirror of our needs of expression online, and offline as well. In a period saturated with digital input and images, for several years the web has become the centre of our lives. In this context, the quotation of Miao Ying included in Chinternet Plus is particularly significant: “Dramatic publicity is never too extreme to sell counterfeit ideology. Be heavy-handed with images; lighting, special effects and the background are just as important as the product itself. They promote the product very well. The eye of the viewer must never rest. Include as much content as possible in the aesthetics. More is better”.

Camilla Fatticcioni

China scholar and photographer. After graduating in Chinese language from Ca’ Foscari University in Venice, Camilla lived in China from 2016 to 2020. In 2017, she began a master’s degree in Art History at the China Academy of Art in Hangzhou, taking an interest in archaeology and graduating in 2021 with a thesis on the Buddhist iconography of the Mogao caves in Dunhuang. Combining her passion for art and photography with the study of contemporary Chinese society, Camilla collaborates with several magazines and edits the Chinoiserie column for China Files.