Museum education in the digital era: strategies and challenges

by Beatrice Rainone

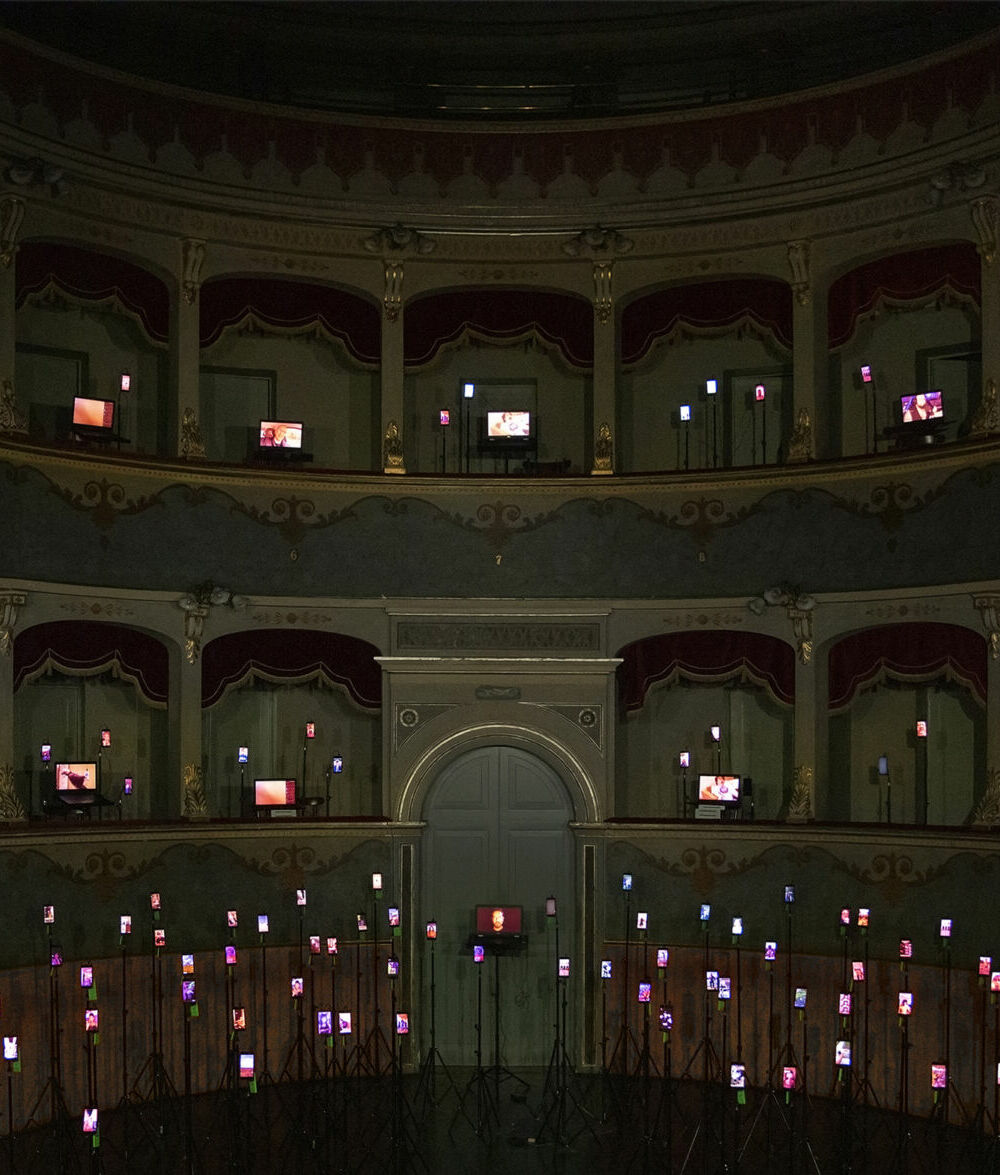

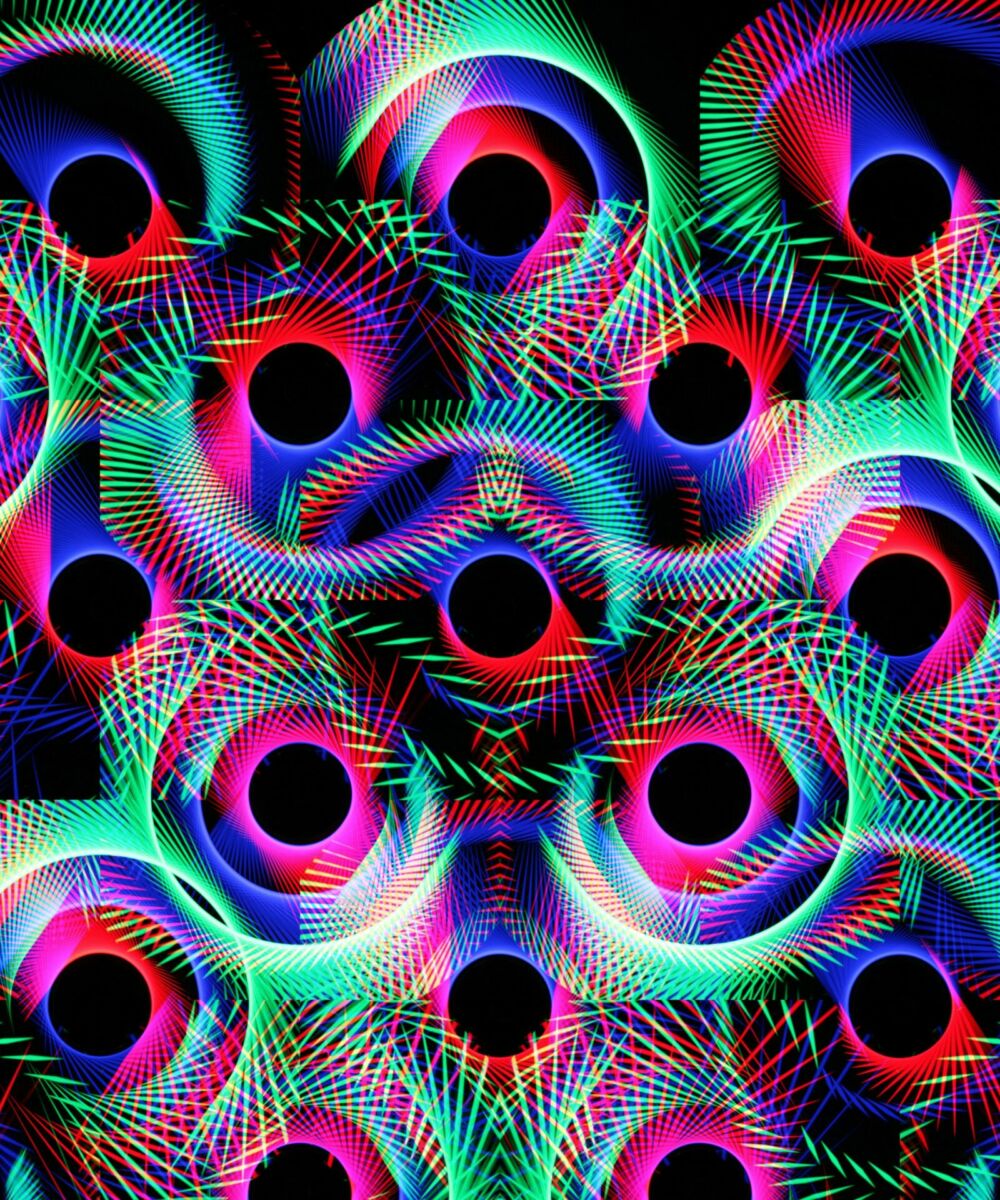

In the professional career of any museum educator, perhaps during a guided tour, sooner or later they will need to contend with digital works, crypto, or the results of an algorithmic process. Whether this refers to TTI (text-to-image) linked to artificial intelligence, or “plain” NFT, the question they must ask themselves is always the same: how do we present it to the museum consumer?

Firstly, any information provided by the educator must necessarily vary according to the target group or individual with whom they are interacting.

It should also be said that it is very common that the consumer hasn’t been in contact with works of this type, and generally, the little he does know is often influenced by negative, or even apocalyptic prejudice (AI will replace us!). Every single artistic or technological innovation, from photography to Jacquard weaving, has always had to combat misgivings on the part of the public. It is the role of the educator to accept this apprehension and understand the concerns of the sceptic, using them as points for reflection in discussion.

As far as children, or groups with accessibility issues are concerned, their interest is less focussed on the technical-creative process, but more on the representation they see before them, and consequently, they are more interested in the impressions and narratives that the work embodies.

It can also happen, and educators must keep this aspect in mind, that they will sometimes encounter “consumers” who are familiar with this way of “making art”, and who will be either zealous supporters or opponents.

As in other spheres, in many fields of contemporary art, critical thinking is never consistent (just as well!). So, the educator must do his best to provide the visitor with the instruments to be able to form his own personal critical judgement; for example, by introducing the terms used in this “metalanguage”, using simple explanations and providing examples of the subject under discussion. The objective is never to convince the other person of the remarkable creative potential or the artistic inadequacy of some work, but to trigger a series of reflections that begin inside the museum, and which, in time, can be enriched and cultivated during conversations with others and on discovering other similar works.

So, how do we lead the consumer towards these narratives?

An explanation of the work and the conception process are fundamental. These must be simple and each specific term must be clearly defined, so that the person with whom we are speaking can, in turn, acquire a grasp of this language.

Every artistic and technological innovation, from photography to Jacquard loom weaving, has somehow had to clash with societal reserve.

It may all seem clear at this point, but before contaminating our consumers with complex “elucidations”, it is essential to lead them towards independent or guided observation.

This practice helps them examine the main components of the work, the overall impression, details, and (why not?) the feelings and reactions that it provokes in the observer. In this way, it is possible to begin a discussion rich in narrative and personal awareness without having to mention AI and similar topics.

In museum education, the core aspect is the artwork itself, and this is placed at the centre of interest because it is closely tied to the encounter and the experience shared with the consumer. Whether the work is a Renaissance masterpiece, an NFT, or machine learning restitution, it interacts with the observer without the need for words, and at least initially, without the need for explanation.

The role of the educator is to mediate between the focal point of what is observed and its observer; it is only after this observation that an initial discussion can be started freely, in which the educator is allowed to intervene by enriching the conversation with technical, creative, historical-artistic, and economic data.

So, how should one conduct the narration of these works? In the same way as any other artistic field. The work of art always speaks for us and before us.

Beatrice Rainone

Born in 1999, is a museum educator and mediator. She graduated in Art History from the University of Florence with a thesis on the concept of reproducibility in crypto-art, and currently works in several cultural institutions in Tuscany, including Fondazione Palazzo Strozzi, Centro per l’arte contemporanea Luigi Pecci, Fondazione Pistoia Musei, Museo del Tessuto.